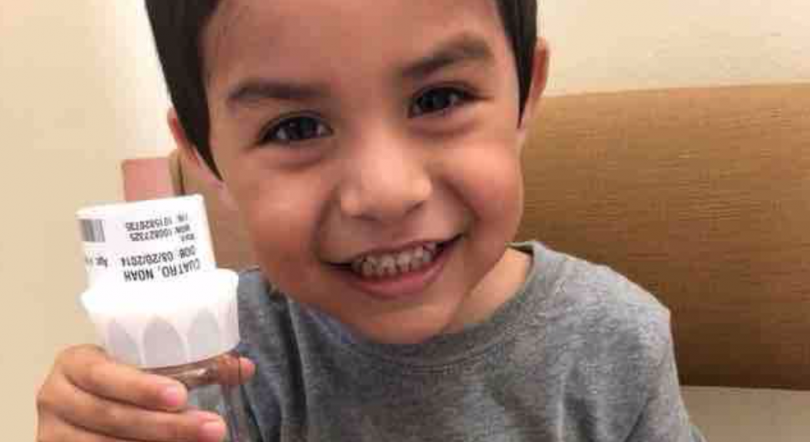

It’s been more than two months since the death of four-year-old Noah Cuatro and, despite the public release last week of a 31-page report by Office of Child Protection, and its director Michael Nash, we still aren’t exactly clear what county officials should have done differently to keep the little boy alive.

As readers may remember, on July 5, the parents of Noah Cuatro called 911, telling the dispatcher that they had found their son unconscious in the communal pool of the Palmdale apartment house where they lived. The boy was rushed to a local hospital and then transferred to Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, where he died on July 6.

Red flags went up right away when doctors who examined Noah found signs of trauma that were not consistent his parents’ claim of drowning.

Thus the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department immediately launched an investigation into the cause of the little boy’s death.

The distress over the death of Noah Cuatro’s was exacerbated by the fact that it occurred a month-and-a-half after a state audit slammed the LA County Department of Children and Family Services for “not adequately” ensuring “the health and safety of all children in its care,” particularly in the area of Palmdale and the Antelope Valley.

(See WLA’s report here.)

Matters were made still worse by the fact that Noah’s death followed two other high-profile deaths of two other little boys, Gabriel Fernandez in May 2013 and Anthony Avalos in June 2018– both of whom died after repeated reports to authorities of abuse and/or neglect in their Antelope Valley homes.

In Noah’s case, his death was additionally upsetting when we learned that, on May 14, Superior Court Commissioner Steven E. Ipson issued an order granting social worker’s request that Noah could be removed from his parents’ care. Yet, despite the order, officials decided not to remove him.

With all this in mind, the county’s Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a motion directing the LA County Office of Child Protection’s Nash (who also happens to be the highly respected former presiding judge of L.A. County’s Juvenile Court), to to conduct an investigation into potential systemic problems that might have stood in the way of preventing Noah’s death.

The 31-page report was delivered to the board on August 30, but was not made public until now.

(Energetic pestering on the part of The Chronicle of Social Change, which has been providing excellent coverage of the story, helped pry the report loose.)

Yet, while it is helpful to finally have the report, its conclusions—which stated that DCFS department members had overall acted correctly regarding Noah Cuatro’s case—-were perplexing.

With all of this in mind, we asked Nash for his thoughts on the report and the issue of what we know—and don’t know—about how and why Noah Cuatro died.

WitnessLA: What you say in the report about the DCFS officials having essentially done everything right in the lead up to Noah Cuatro’s death, makes logical sense when one reads the whole of the report. But, at the same time, the conclusions feel very unsatisfying and unsettling.

Michael Nash: Well, of course. Because you have a dead child.

WLA: Right. And, while we don’t want to unnecessarily yank kids away from their families, we also hoped the report would, at least, illuminate the points where interventions could have been made to prevent the death of this little boy.

With that in mind, what should we take away from this report?

MN: I’m not sure we can come away with a whole lot at this point because we still don’t know what happened. That’s the bottom line. We know there’s a dead child and everyone is anxious to find somebody to blame.

WLA: I don’t know if it’s blame we’re looking for, but we certainly want to know what should have been done differently.

MN: First of all, part of the reason this case seems to have drawn interest is because of the existence of the removal order.

WLA: Yes, a lot of us did fixate on the fact that, even with a removal order from a judge, no one still managed to get this little boy out of harm’s way.

MN: Okay, but let’s understand a couple of things. To call [the judge’s action] a removal order is really a misnomer. As I explained in the report, what happened is you had a social worker who filed a report, and the court signed it and said ‘you have the authority to remove this child.’

It was not that someone was disobeying a court order in not removing the child.

WLA: That was admittedly confusing for those of us who are civilians.

MN: Right, which is why in the report I wanted to make it clear that, while we call it a ‘removal order,’ it’s really just the authority to remove the child—in the absence of exigent circumstances.

If there are exigent circumstances, of course, you don’t need any order from the court to remove a child. But nobody’s claiming there were exigent circumstances in this case.

My point was that seeking a removal order, in this case, was premature. And DCFS recognized that because they made an attempt to withdraw the order before the judge signed it, but it was too late.

WLA: So what does all this tell us?

MN: I was making three points with the report. Number one, that DCFS shouldn’t have sought the order without completing their investigation [into their concerns]—which they hadn’t done.

Number two was that there wasn’t any problem with the judge signing the removal order because the information [in the document he was given] sounded serious.

But my sense was that the judge didn’t know that the information hadn’t been investigated. And when DCFS did complete their investigation, the information, which had really sounded serious, was not supported.

[more on those allegations in a minute]So, number three, the workers were right in not removing the child, at that point. Because removing a child can be very traumatic. Although, the social worker’s gut instinct said ‘there’s a problem here….’

WLA: Which turned out to be right…

MN: …But, we don’t take court actions on gut instincts. Still, the most serious facts the social worker had at the time suggested there were still some issues with this family, and that DCFS shouldn’t terminate this case.

WLA: But they didn’t necessitate a removal…?

MN: Right. So the child was returned to his parents, and the court said to participate in a counseling program, give the great grandmother visits, and keep DCFS apprised of your address.

WLA: And did the parents comply?

MN: Not really. They didn’t do the counseling, they didn’t keep DCFS apprised of where they were. But the department always found them.

And when the social worker saw Noah and the other children a week before he died, he was fine. The mother had just had a new baby, and there were some concerns, so DCFS was checking up on them. And, DCFS was also moving forward to enhance the agency’s involvement with the family.

WLA: It honestly sounds like there were a lot of concerns including, as I remember from the report, the mother telling hospital officials after she had a new baby in June of this year that it wasn’t her baby, and other crazy things.

MN: Once again, in the absence of information that the child was being severely neglected or abused—other than hearsay information, which the supposed witnesses denied—there was no evidence of abuse. There was some worry that, when DCFS came, he may have been coached before the visit, and he probably was. But, he said he was fine, and he looked fine. He seemed comfortable in his surroundings. And there was nothing physically wrong with him or any of the other kids.

At the end of the day, the most important issue is safety. We don’t want to take children away from their families. Yet, if they’re not safe, we do.

But, other than the allegations that the so-called witness recanted, there was no allegation of child abuse.

More details of the worrisome backstory

On the other hand, Nash explained as we continued to talk, DCFS had been involved with Noah Cuatro’s family ever since Noah was born.

The first involvement occurred in August of 2014, when there was the suggestion that Noah’s mother had injured his older brother as a baby, fracturing his skull, so DCFS took away both children right after Noah’s birth

“They took him right out of the mother’s arms,” said Nash. For nine months, Noah and his brother were placed in the care of their great grandmother, Eva Hernandez,—who is now taking steps to sue the county.

“But after nine months the department dismissed the case,” Nash explained, because after an investigation, “the evidence didn’t show the mother did it.’” So the two little boys went back home.

The second time Noah was removed from his parents’ care was in November 2016.

“That was a case of neglect,” said Nash.’ And he was certainly neglected.”

Specifically, Noah was diagnosed with failure to thrive, developmental delay, and congenital hypertonia—a hard to diagnose stiffness of muscles and joint rigidity sometimes seen in young children. Part of the accusation of neglect was that Noah was “medically neglected” by his parents who failed to take him to eight scheduled medical appointments.

So again Noah was taken from his parents.

“But then the parents theoretically did what they needed to do to get their child back,” said Nash.

Noah was returned home in November 2018.

In May 2019, some additional accusations of possible abuse by an anonymous caller who alleged that Noah was being hit and cursed at by his father, that the father was also hitting Noah’s mother, and that there might be issues of sexual abuse.

The led to the submission to the judge for a removal order. But, an investigation failed to prove the allegations, and when relatives mentioned in the hotline call were questioned, they disputed what the caller had said, according to the report.

Then in visits by a social worker on June 28, Noah was described as being “in good spirits and reported that he was doing well.”

Waiting for the sheriffs

WLA: So, again, where are we? Where does this leave us in terms of deconstructing what led to Noah’s death?

MN: As I said, when you dig down into it. It appears that the department did everything right.

And, at the same time, as you point out, we’re all very uncomfortable because we have a dead child. And, what’s worse is, we don’t know why.

WLA: So, now does this mean that the next step is in the hands of the LA County Sheriff’s Department? And we can’t know more until we have those results.

MN: Yes, they’re conducting an investigation. It’s been over two months, and they’re playing it very close to the vest. So we don’t know anything about what they’re finding. All we know is the sheriff’s people are working on it.

And so we wait, said Nash.

More as we know it.