When the COVID-19 pandemic began its frightening rise in the United States, justice advocates were quick to call for prison and jail releases, for obvious reasons of health and safety, and the jail and prison populations indeed began to fall. Yet, a little more than a year later, the much needed decarceration appears to have stalled, according to a new report published Monday by the Vera Institute of Justice.

Overall, incarceration numbers across the U.S. dropped an unprecedented 14 percent in the first half of 2020—from 2.1 million people locked up to 1.8 million. Yet, over the second six month of the pandemic, the numbers declined far less from fall 2020 to spring 2021, mainly because jail populations across the nation began to creep back up.

In order to arrive at their estimated numbers concerning the nation’s incarcerated population, Vera researchers sampled approximately 1,600 jail jurisdictions, 50 states, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the U.S. Marshall Service, and ICE.

Among the report’s findings was the fact that jail populations in rural counties dropped by 27 percent from 2019 through March 2021, the most of any region.

But, as noted above, it didn’t last.

“The historic drop in the number of people incarcerated was neither substantial nor sustained enough to be an adequate response to the pandemic,” wrote the report’s authors, who note that incarceration in the United States still remains a “global aberration.”

CA prison numbers & LA jails

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the nation’s second largest prison system, to some degree followed the national pattern, starting out with a pre-Covid population of 125,507 in 2019, which came down to 114,966, by mid-2020, for a drop of 8 percent. By mid-2021, after COVID deaths spiked painfully among vulnerable incarcerated people in the state’s facilities, and busloads of already infected people were transferred into San Quinten prison, with tragic results, both Governor Newsom and CDCR officials caved into pressure and let at least some people out. The CDCR population came down to 115,225, bringing the overall drop since 2019 down to 23 percent.

Across the state, however, jail numbers dropped by 20 percent by midyear 2020, but then edged back up by this spring, cutting the drop since 2019 back to 12 percent.

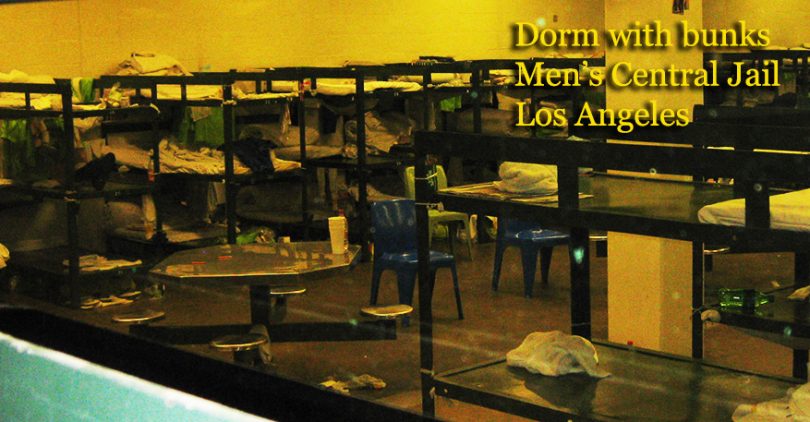

The jail patterns the Vera report describes are also reflected in Los Angeles County home of the nation’s largest jail system. Starting in March 2020, the LA Sheriff’s Department, plus the LA Police Department, and all other law enforcement agencies in the county, began working hard to reduce the number of people in local lock-ups through a variety of means, hoping to lessen the looming “incubator” threat inside the facilities, because of the deadly pandemic that had suddenly arrived.

The fears among local officials of how the virus would affect men and women inside the county’s jails, were demonstrated on March 23, when Supervisor Kathryn Barger, who was, at the time, the Chair of Los Angeles County Supervisors, issued an Executive Order that asked LA County’s Health Officer to conduct an “immediate assessment” of the county’s jails for the purpose of identifying any and all additional “necessary and appropriate measures” to prevent COVID-19 from spreading wildfire-like through the nation’s largest jail system.

During that same period, Sheriff Alex Villanueva ordered the release of anyone from the jails who had less than 30 days left on their sentence, and members of the various law enforcement agencies were told to only arrest those who were a threat to public safety. Also, when possible, deputies and officers were told to “cite and release,” rather than dragging people to jail where too many cannot afford to bail out.

As a result, during those first frightening weeks and months of COVID, arrests in the county fell from approximately 300 per week, down to 60 per week, bringing the jail population down from a Feb. 28, total of 17,076 to 16,459 by mid March 2020. By late summer, the numbers dropped still farther reaching 11,723 by August 2020.

As of this writing, June 9, 2021, the population in the LA County jail system is back to 14,843 with 3,439 awaiting transfer to state prison. These are, of course, far better numbers than before COVID arrived, but unnecessarily high, according to justice advocates and Vera researchers.

Jail population and race

Vera also points to the fact that, despite the gains of at least some decarceration progress, according to recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, racial inequity worsened as jail populations declined through June 2020.

Specifically, note the Vera authors, the BJS report found that the national jail incarceration rate of Black people declined 22 percent between 2019 and 2020.

Sounds good, but during that same period, the jail incarceration rate of white people declined 28 percent.

The same BJS report found that, during this time the incarceration rate of Latinx people declined 23 percent and the jail incarceration rate of Asian American people had declined 21 percent, all less than the fall for white people.

Similarly, evidence from the Bureau of Justice Statistics showed that racial inequity got still worse as jail populations continued to decline through 2020.

In Los Angeles County, there are also “persistent racial disparities in who is incarcerated,” according to another recently released VERA report, with Black people — and especially Black women — suffering disproportionate rates.

Although the jail population decreased at the beginning of the pandemic, racial disparities worsened for Black and Latinx/Hispanic people.

Women, jail and mental health

An August 2020 study ordered by the LA County Board of Supervisors, which analysed various characteristics of the county’s jail population found that, during the pandemic, Black women were spending the longest days in custody, and Black people with mental health needs were released at significantly lower rates than their white counterparts.

On the topic of those with mental health needs, in the Los Angeles County jails, the percentage of men and women with mental health needs was down in the Spring of 2020. Yet, that drop didn’t last either.

Yet, as of today, those with mental health needs represent 38 percent of the whole system population, which is a rise of 21 percent over the last year.

When the numbers are broken out by gender, the percentage of women incarcerated in the county who have mental health needs now comes in at an alarming 68 percent of the entire population of women in LA jails.

All across the nation, this pattern of once-lowered jail populations — across the state and the nation — slowly rising back up, according to the authors of the just released Vera report, speaks more, the authors say, to the “political, economic, and social issues” surrounding the nation’s incarceration policies, than it does any reasons pertaining to public safety.

[…] CA’s Jail & Prison Populations Went Down During COVID, But Now The Jail Numbers Have Crept Bac… Celeste Fremon, WitnessLA […]