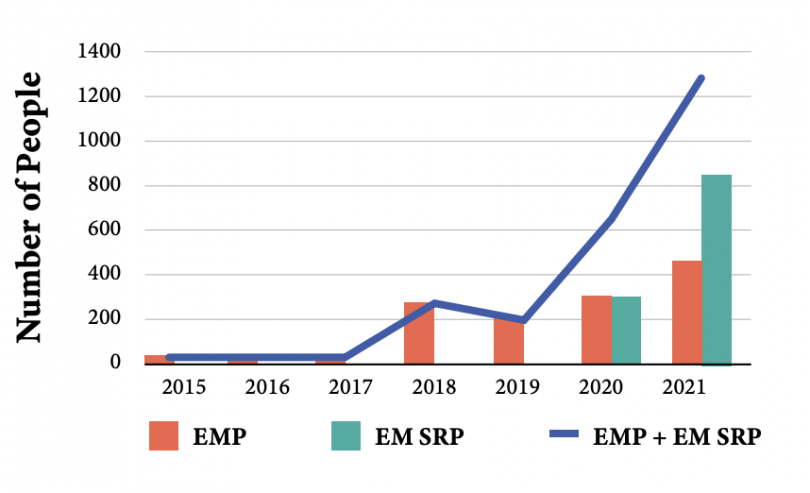

In Los Angeles County, the number of people forced to wear electronic ankle monitors as a condition of pretrial release has increased 5,250% in six years — from 24 people in 2015 to 1,284 people in 2021, according to a report from UCLA School of Law’s Criminal Justice Program.

Over the course of 2021, five times as many people were placed on electronic monitoring (EM) pretrial as people monitored after a conviction. This means that the bulk of the rise of electronic monitoring has impacted people not proven guilty of a crime.

In LA, the courts decide who will be monitored, and LA County Probation oversees the monitoring. Soon, however, LA County’s new Justice, Care and Opportunities Department will take over probation’s pretrial operations.

Generally, the county fits residents with ankle monitors through two particular programs. The first and oldest, Electronic Monitoring Program (EMP) runs in all two dozen courthouses and deals with both pretrial and post-sentence individuals. The second, implemented in 2020, the Supervised Release Program (SRP), is a pilot program running out of two courthouses. This program strictly handles pretrial cases.

One of the two SRP courthouses is in Lancaster, where judges default to electronic monitoring, requiring it in 92 percent of cases referred to SRP, despite an alternative monitoring option that does not require ankle trackers.

SRP was one of 16 pretrial pilot programs the California Judicial Council funded across the state. While there were many factors in play, including bail reform efforts and COVID-19, in Los Angeles, the arrival of the SRP pilot program corresponded with the largest increase in electronic monitoring over the six year period studied by report author Alicia Virani, the Gilbert Foundation Director of UCLA Law’s Criminal Justice Program.

The state’s 2019-2020 Budget Act stated that the funding must be used to expand monitored and “own recognizance” release, and that courts should use the “least restrictive interventions and practices necessary to enhance public safety and return to court.”

Better ways

Community-based justice reform advocates would argue that monitored release amounts to “e-carceration,” and is incredibly restrictive with little benefit to the county or community safety.

Most people on pretrial EM in LA are spending a median of at least 65 to 71 days monitored while waiting for trial, according to the report. One-third of those people spend more than 6 months on EM.

Yet, just 45 percent of people monitored through the SRP successfully completed the program in 2020.

Moreover, 94% of people who were dropped from the older program, EMP, were terminated for “non-compliance,” or technical violation, rather than for “absconding” or a new arrest.

During a March 24, 2022 meeting of the Civilian Oversight Commission overseeing the LA County Sheriff’s Department, Ivette Alé, a JusticeLA coalition leader, expressed concern that the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department would also ramp up use of electronic monitoring as part of its own efforts to reduce the pretrial population in the jail system.

“It’s important to look to alternative ways to release people that actually support their return to court — things like text message reminders, transportation to court, child care,” Alé said. Providing child care for pretrial individuals, she said, is a strategy that “Orange County, our neighbors, have already implemented to help folks return to court.” These strategies are also far less costly than EM, she said.

“It doesn’t have to be jail OR electronic monitoring,” Eunisses Hernandez, co-founder of La Defensa and an LA City Council candidate, wrote in a December 2021 tweet. “It can be intensive case management, housing, & more than just expanding the carceral system through tech.”

In LA, electronic monitoring is not just used for adults on pretrial release or probation, but also for kids entangled in the juvenile justice system. A 2020 Berkeley Law report revealed that there were 3,485 unique youths who were put on EM in LA County, in 2017.

The monitors are also frequently used for people leaving state prison who will spend time on parole in their communities.

“You’re not free yet.”

In the case of Angel Zubiate, a member of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, the news that he would have to wear an ankle monitor while on parole came as a surprise.

In fact, Zubiate was home for two months, he said, before his parole officer told him he would be transferred to the gang unit of the parole office and put on an ankle monitor, in August 2019.

During the first month of his time back in his Riverside County community, Zubiate said he was doing well. His check-ins with his parole officer were going smoothly, he passed the test for his driver’s license, and got a job. “Everything happened really fast for me.”

Then came word of the new, onerous conditions of his parole, a message which, for Zubiate, translated to: “You’re not free yet.”

“It was puzzling to me,” Zubiate said, to learn that the parole office wanted to surveil his every move during the two years he would spend on parole. He had been incarcerated for a gang-related crime, and his status in prison was “gang affiliated.” This, according to the parole office, made Zubiate a threat to the community.

Yet, his track record from his time in prison should have indicated otherwise, Zubiate said. He was a teenager, just 16, when he went to prison for attempted murder. Over the course of his 15 years behind bars, Zubiate said he had done everything right, taken all the right courses, and displayed personal growth.

Thus, being put on an ankle monitor, Zubiate said, felt like the system was telling him, “You may have participated, and improved [yourself], but we still don’t believe you. We’re going to track you like an animal because we’re still fearful of what you’re capable of.”

Being on an ankle monitor is far more invasive and more challenging than completing the terms of non-GPS-monitored parole. It presents yet “another barrier,” to thriving after prison.

“It was very stressful, and just discouraging,” said Zubiate.

Faulty devices

Swimming was also out of the question, making beach trips with his family and pool days at his sister’s house less enjoyable. He wasn’t supposed to submerge the device, and wearing shorts in public was embarrassing.

The technology is outdated. It feels like having a bulky 90’s pager strapped to your leg, he said.

Getting his ankle monitor wet, even in the shower, would sometimes cause it to glitch and send notifications to the parole office. If that happened while he was showering, he said, he might come out to multiple missed calls. He also had trouble with his monitor cracking and breaking as he was doing physically strenuous work at his construction job. This would also alert the parole officer.

And when they couldn’t reach you, he said, “they would literally go down the list, calling anybody that’s related to you, even your job.”

Thankfully, Zubiate’s boss was understanding, both about the phone calls, and about the fact that Zubiate might have to take off work to drive from LA or Orange County back to Riverside to change out the faulty device.

Beyond the inconvenience and the lost wages, it was uncomfortable to have to tell his coworkers why he was wearing an ankle monitor.

“The first thing they’re gonna be thinking is, ‘This person’s violent,’” Zubiate said.

They might, jump to the conclusion that he was a sexual predator, he added. “I definitely don’t want to be looked at in that light.”

At one point, after being hired for another job — this one in sales — and passing the live scan, Zubiate wore slacks to work that were just fitted enough that you could see the outline of his ankle monitor. A supervisor asked him about it, he said. Shortly after, he was let go.

Zubiate also said the monitor made sleeping difficult. It had to be plugged into the wall for at least three hours in the middle of night to fully charge for the day ahead.

There were times, he said, when he would move in his sleep and rip the cord out of the wall. As a person who spent 15 years in prison, having to be attached to the wall via an extension cord made the experience more degrading. It felt almost like another chain.

The hard plastic of the device and band would also dig into his skin, making exercise painful.

Members of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition would often go on long hikes meant to prepare them for union pre-apprenticeship, he said.

During these outings in nature, you’d have to contend with “the back of your ankle always ripping open because of physical activity.”

Restricted movement

According to CA’s conditions of parole, Zubiate was allowed to travel within a 50 mile radius of home without permission, as long as he was away from home for less than 48 hours.

With these boundaries in mind, Zubiate decided to take a mini overnight vacation, booking a hotel room in Fullerton about 30 minutes away from his home. He had never stayed in a hotel suite before, he said.

In the middle of the night, however, he got a call from the parole office ordering him to return home as soon as possible. So, Zubiate checked out of the hotel he paid for and drove back to his house.

Later, when Zubiate got approved for a rental property he said would have been great for him and his son — so close to where he currently lived that he could “throw a rock at it” — his parole officer said the move was out of the question. The new place, just over the county line, was out of bounds.

The stacked up rules and lost hours of work were demoralizing, and made Zubiate’s transition back to his community more difficult than it might have been otherwise.

Earned freedom

People who come home from prison, Zubiate said, should be accepted. When a person serving an indeterminate life sentence is released onto parole, they have worked hard for that freedom, Zubiate said. “It’s earned. It’s a long process.”

When you exit prison, he said, “those milestones that individuals accomplish should still speak toward your acceptance here in the outside world. You shouldn’t have to go backwards when you already earned that place of trust.”

The state’s justice system, he said, is essentially saying, “We’re trusting you, as a person that committed a crime so many years ago, to be released into society because you’ve proven that you have rehabilitated yourself.”

At that point, said Zubiate, “there’s no reason to put an ankle monitor on your leg.”

[…] source […]