On June 21, 2018, 10-year-old Anthony Avalos died as a result of long-term abuse and multiple kinds of torture, allegedly by his mother and her boyfriend. The horrific nature of this little boy’s death, and the fact that multiple calls suggesting abuse were made to Los Angeles County’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), caused policymakers on a local and state level to demand a better understanding of what in the world had gone so terribly wrong.

(Avalos’s mother, Heather Barron, and her boyfriend, Kareem Leiva, are charged with murder.)

This question resulted in the state’s Joint Legislative Audit Committee directing California State Auditor Elaine M. Howle to look at the practices of LA County child welfare system, the largest such local system in the nation, to find out how DCFS failed to see the danger Anthony Avalos was facing in his home, despite the repeated calls reporting abuse.

The 36-page audit, with its straight-to-the-point title of “Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services: It Has Not Adequately Ensured the Health and Safety of All Children in Its Care, was delivered to state and county officials on Tuesday, May 21.

The report’s bottom line conclusion was that LA County’s foster care system “unnecessarily risks the health and safety of the children in its care” in a variety of alarming ways.

“As a result,” wrote the state’s auditor, “the department leaves some children in unsafe and abusive situations for months.”

The report then detailed exactly how the department was dangerously failing some of the county’s kids, then followed up with 13 recommendations laying out how DCFS should fix its problems.

With the report’s findings in mind, on Tuesday, the LA County Board of Supervisors are expected to approve a motion authored by LA County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, that will instruct the Director of DCFS, Bobby Cagle, the Executive Director of the Office of Child Protection, Michael Nash, and the county’s CEO, Sachi Hamai, to “provide an analysis of the recommendations included in the State Audit,” and what ought to be done about them—and report back to the board in 60 days.

The 151-day lag time

In general, here’s what the report found:

When LA County’s child welfare department receives an allegation of child abuse or neglect—a referral—it routes the referral to one of the county’s 19 regional offices for an in-person investigation and, also, ongoing case management, if the situation warrants it.

State law requires that a social worker must begin their investigation within 24 hours, or within ten days, depending upon the severity or circumstances of the referral.

Depending on what the social worker finds, a series of additional actions may be further triggered, including the removal of the child or children from their parents’ care.

In order to see how LA was doing with these basic functions, the auditor and her team reviewed the manner in which 30 random cases of possible child abuse and neglect were handled by the department. They found signs of unsettling patterns with many of the cases they reviewed.

For instance, out of those 30 referrals, only 19 out of the 30 were investigated within the correct—and safe—time frame.

“For one referral,” the auditor wrote, “the social worker made one unsuccessful attempt to contact the family within 24 hours, but did not make subsequent attempts.”

This referral happened to be the kind that mandated a 24-hour response—meaning they should do an in-person assessment, not just make a one-time effort to reach the family

Eventually, a department member sought out and found the family that was the subject of the referral, but only after 151 days had passed since the initial call. And, once the social worker actually made an in-person visit, the department “removed the children” from what they deemed to be “an unsafe home situation.” Five months after the fact.

Dangerous delays

After the initial in-person visit, if a further investigation is required, California law generally requires counties to complete this investigation within 30 days of the date that the social worker has an in‐person response with the child.

If a social worker is not able to initiate an investigation within the first 10 days of a referral, he or she must close the investigation within a maximum of 40 days from the referral date.

Of the 30 investigations reviewed for the audit, DCFS completed only nine investigations within the required time frames. Of the other 21 cases, six investigations went on for longer than

90 days.

And one investigation, write the auditors, “lasted over 400 days.” In that time, the social worker visited the potentially endangered children “only three times.”

In another situation, the social worker had only one in-person visit with the family, and never attempted anything more, leaving the children in what turned out to be an unsafe situation, according to the auditors.

Things got so bad, that while the investigation was still open—with zero new visits taking place—law enforcement notified DCFS that they had removed the kids as a result of another allegation.

Mistakes and more mistakes

The problems the auditors found went on from there, revealing that mistakes occurred at a frequency that cannot ever be viewed as acceptable.

When social workers completed their “safety and risk assessments,” the auditors found 12 of the 30 assessments they reviewed “were not accurate.”

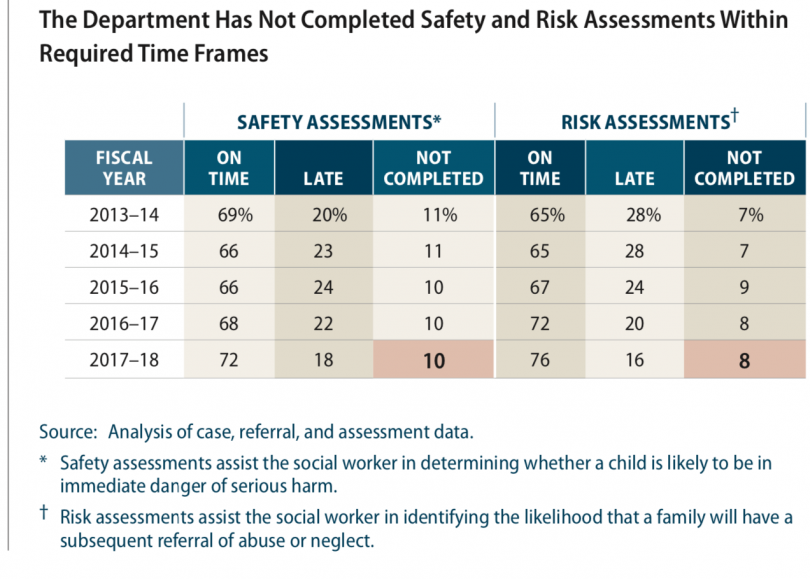

(Safety assessments are the most urgent of the two kinds, and are to determine whether a child is “likely to be in immediate danger of serious harm.” Risk assessments are important but less urgent, and help a social worker identify the likelihood that a family will have a subsequent referral of abuse or neglect.)

In five of the 30 safety assessments auditors reviewed, social workers did not accurately identify or attempt to address safety threats present in the homes.

In two instances, the social workers erroneously performed the safety assessments for homes and caregivers who were not the subjects of the referrals.

In three other instances, social workers filled out safety assessments without actually visiting the children’s homes. Nevertheless, wrote the auditors, the social workers determined “that the homes were safe and without hazards.”

Similarly, of the 30 risk assessments they reviewed, 12 were inaccurate, “largely because social workers failed to consider important risk factors, such as past domestic violence “in the homes, or results of previous department investigations.

“The social workers omitted this information from assessments even though the information was available to them in the case files.”

LA child welfare has a failsafe to guard against such errors, which consists of having a supervisor review the social workers’ reports. Yet, according to the auditors, the supervisors either failed to catch the mistakes, or they performed the review so staggeringly late that it no longer applied.

“Of 60 assessments we reviewed,” the auditor’s wrote, supervising social workers approved 17 investigations after they were already closed, and never approved two others at all.

“In one instance, the supervisor took 125 days to review and approve the initial safety assessment.”

Other areas of concern included the failure to conduct “reunification assessments” in a timely fashion, without which it was unclear whether or not was safe to return kids to their homes.

And in the cases when family reunification was likely indicated, this meant it could be greatly delayed. In other words, the lack of an appropriate assessment could prolong the trauma of a child or children being unnecessarily separated from capable parents.

The department was also disturbingly inconsistent, according to the auditors, in performing the required home inspections and criminal background checks before placing kids removed from their families with relatives.

Statistically, kids do much better with family than strangers. Relative caregivers are always preferable. But, some family members have their own problems that make them unsuitable.

Thus it was discouraging to learn that, of the 22 relative placements the auditors reviewed, DCFS only performed 16 of the required in‐home inspections prior to placing kids with other family members. Furthermore, the department appeared to only to complete “pre‐placement criminal background checks” for five of the 22 placements.

The audit also noted that all of the above problems occurred when the number of kids receiving child welfare services in LA County had dropped, and “despite budget increases that allowed the department to hire more social workers and reduce caseloads.”

Six years ago, LA reeled from the terrible death of 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez in 2013, another child whose ongoing abuse was repeatedly brought to the attention of LA County social workers. In response to Gabriel’s murder, the board of supervisors caused the creation of a Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection, made a series of important recommendations, many of which were put into place, including the welcome hiring of Judge Michael Nash as Child Protection czar, and the push for the board of supes to allocate the cash to hire more front-line social workers, especially in the Antelope Valley, where Gabriel Fernandez died.

And now this new audit has revealed that the department still has serious deficiencies.

Where to go from here

In addition to the flagging of problems, the audit includes a list of thirteen recommendations, all of which are aimed at making the system more rigorously accountable to its own and the state’s rules.

DCFS Director, Bobby Cagle, who took the reins of the large and complicated department on December 1, 2017—seven months before Anthony Avalos’ death—has written a response to the audit explaining how he has already putting improvements into place. Cagle is generally considered a capable leader with a good sense of balance.

“My pursuit daily is to assure that this doesn’t happen to a child,” Cagle said in August of last year after Judge Nash delivered own his analysis of what DCFS needed to learn from Anthony Avalos’ tragic death. “One of the frustrations that we have is that we have no known interventions that can be 100 percent effective, 100 percent of the time.”

Still, given the seriousness of the problems flagged, the supervisors are clearly correct in instituting their own mechanism to make sure the recommended reforms are put into place ASAP, and scrupulously monitored.

At the same time, the reforms must be accomplished without triggering a reactive pendulum swing of LA County’s foster care policies, which could, in turn, cause children to go through the life-altering trauma of being removed unnecessarily from their families in an effort to prevent future tragedies, like that of Anthony Avalos.

Editor’s note

If you are interested in the topic of child welfare, and haven’t yet seen the HBO documentary, “Foster,” by filmmakers Mark Jonathan Harris and Deborah Oppenheimer…don’t under any circumstances miss it. Seriously. (But have plenty of Kleenex on hand.)