A California appeals court has ordered the California Attorney General’s Office to explain why an indigent 64-year-old San Francisco man accused of a low-level crime must remain behind bars with bail set at an unattainable $350,000.

The First District Court of Appeal’s order in the Kenneth Humphrey case indicates that the appellate court may take up the issue of cash bail in California.

Humphrey, a retired shipyard worker, has sat in San Francisco County Jail since he was arrested on May 23. According to the defendant’s habeas petition, Humphrey, who is African American and lived in a housing development for indigent seniors, was arrested for allegedly following a 79-year-old neighbor—identified in the petition as “Elmer J.”—into his room and stealing a bottle of cologne and $5.

The defendant was charged with first-degree residential robbery, first-degree residential burglary, inflicting injury (not great bodily injury) on elder and dependent adult, and theft. Initially, Humphrey’s bail was set at $600,000, but was later reduced to $350,000.

“This case was outrageously overcharged from the beginning,” San Francisco Public Defender Jeff Adachi said. “To add insult to injury, Mr. Humphrey has been kept behind bars without any consideration of releasing him on pretrial supervision. It is fundamentally unfair to lock people up solely because they are too poor to buy their freedom.”

According to a petition filed by Adachi and the nonprofit Civil Rights Corps, setting bail that high under the circumstances of Humphrey’s case violate’s the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on excessive bail.

When defendants cannot afford to pay their entire bail amount, they can pay a non-refundable 10 percent—in Humphrey’s case, $35,000—to a bail bondsman in order to secure their release. For many defendants, including an indigent senior living in an affordable housing development, $35,000 puts pretrial release out of reach.

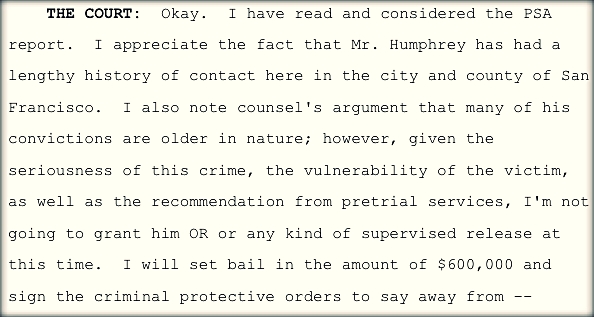

When the judge set bail at 600,000, he said he would not grant Humphrey “any kind of supervised release,” because of “the seriousness of this crime [and] the vulnerability of the victim.”

The problem, according to Civil Rights Corps attorney Katherine Hubbard, is that prosecutors and judges can’t use exorbitant bail amounts to keep poor defendants whom they don’t want to release behind bars.

Instead, when a prosecutor believes that an arrestee poses a threat to public safety, the prosecutor is required to ask that bail be denied outright to the defendant. Then, within five days after arraignment, a judge would have to hold a detention hearing, according to the Constitution. If during the detention hearing, the judge found clear evidence that the arrestee would be a danger to the public if released, the judge could then order the person to be detained with no option for release.

In this case, according to Civil Rights Corps attorney Katherine Hubbard, the prosecutor asked for an extremely high bail amount for a man charged with low-level felonies, presuming that the defendant could not pay.

Humphrey, the petition states, is “entitled to bail as a matter of right,” due to a lack of evidence that the man poses a danger to the public or would be a flight risk.

During the arraignment, the defense requested release on recognizance based on Humphrey’s age, his financial situation, the fact that the defendant’s prior convictions were more than 14 years old, and the fact that the victim suffered minimal loss of property.

According to the petition, the court did not conduct an inquiry into whether the defendant could pay the bail amount, or consider non-monetary alternatives to cash bail.

According to Hubbard, it’s extremely common for courts to “evade this constitutional process” required to detain someone on the basis of public safety. “I don’t know if the detention hearings are actually happening anywhere,” Hubbard told WitnessLA.

In another Civil Rights Corps habeas case, a district attorney admitted that she didn’t even know what the detention hearing was, Hubbard said.