THE DOJ HAS A NEW LAW ENFORCEMENT DATA GATHERING PLAN, BUT MANY CRITICS AREN’T THRILLED

On Thursday of last week, the U.S. Department of Justice announced a new plan to gather crucially important nationwide data on law enforcement interactions with civilians in general, and on the use of force by law enforcement officers in particular.

On Friday, Witness LA joined author, and former Los Angeles Times police reporter, Jim Newton (now editor of Blueprint), and New York Times reporter, Eric Lichtblau, on KPCC’s AirTalk with Larry Mantle to discuss the good, the bad, and the not-so-promising aspects of the new plan.

Here’s the deal: According to Attorney General Loretta Lynch, this new effort at data collection is an attempt to close a gap in an existing law passed in 2014 called the Death in Custody Reporting Act. The DCRA (that is pronounced by experts, in all seriousness as dic-rah) made it a requirement for police and other law enforcement agencies to submit data about people who died during an interaction with law enforcement or in their custody.

A good new step forward, right? Well, maybe not. According to a long list of advocates and experts, the lack of an enforcement mechanism to mandate that law enforcement agencies actually fork over the necessary information, plus the new plan’s flawed methods for data gathering, does not bode at all well for anything resembling success.

THE PAST IS NOT CHEERING

According to 2014’s DCRA, in order to persuade agencies to participate, said agencies could also be fined by the AG for not reporting these incidents.(“Could” is the operative word here.) But such arguably weak enforcement mechanisms are not in place for the new reporting system of non-lethal uses of force interactions.

As WitnessLA reported on Friday, thus far, even when it comes to the two states that already have mandated reporting of fatal shootings by law enforcement—namely California and Texas—-things have not gone especially well, according to a recently-released study conducted by researchers at Texas State University at San Marcos.

The study’s authors looked at data reported over a ten-year period by police and sheriff’s agencies in those two states, then placed those numbers side-by-side with data for the same period gained via other sources—news stories, press releases from police departments, coroners, and the like. When the researches compared the two sets of figures, they found that California was missing 30 percent of its total officer involved fatal shootings, which came to 440 incidents. Texas agencies missed reporting around 220 OIS deaths, or 25 percent.

And although, in California, large law enforcement agencies like the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department (34 unreported deaths), the Los Angeles Police Department (21 fatalities missing) and the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department (12 missing incidents) led in this undistinguished sweepstakes, in many cases the discrepancy seemed more an artifact of problematic record keeping, not deliberate data tweaking.

THE BAD ACCOUNTING FACTOR

The study also noted that some of the biggest gaps in data came from the small law enforcement organizations around the two states, some of which may be deliberately underreporting to protect their agencies from bad PR, but there also seemed to be a lot of sloppy record keeping.

In fact, according to LASD spokesperson Nicole Nishida, many of the department’s 34 missing officer involved fatal shootings were due to a “clerical error” caused by a switch in reporting forms.

This last, brings up one of the most pressing objections to the new plan flagged by a list of 67 organizations including the ACLU, the AFL-CIO, the NAACP, the Southern Poverty Law Center, Amnesty International, and more. According to this group of concerned advocates, the new DOJ plan weakens the already-faulty 2014 collection mechanism by turning over data collection to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, not the states.

Worse, as the ACLU, et al, noted, the “proposal indicates that BJS will rely primarily upon publicly available information (“open-source review”)” for its data collection.

This means, as the 67 groups wrote in an open letter to Attorney General Lynch, “that should The Guardian and the Washington Post decide to continue to invest in this research, those news outlets will continue to be the best national sources for data on deaths in police custody.” That’s not how it should be.

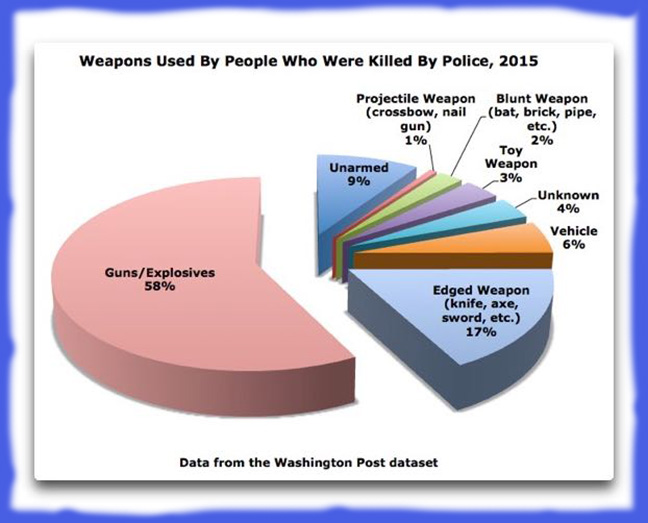

(At this point in time, the Guardian’s project The Counted and the Washington Post’s data gathering project provide the closest to accurate data that we have.)

CARROTS & STICKS

The advocate group also stressed that that “some kind financial penalty is critical to successful implementation” of both DICRA and the new program. “Voluntary reporting programs on police-community encounters have failed,” they wrote. “Reportedly, only 224 of the more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies reported approximately 444 fatal police-shootings to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 2014, though we have reason to believe that annual numbers of people killed by police exceeds 1,000.”

The DOJ already awards close to $4 billion in grants annually to local agencies to collect and report data on incidents of police use of force on civilians and other police-civilian encounters. Advocates propose that such discretionary grants should be conditioned upon providing data.

Texas State University researcher Howard Williams—who, by the way, was a police officer for 36 years, first for the Austin PD, and then as the chief of police in San Marcos, Texas—agrees that much of the problem is that the reporting has, in the past, been voluntary—a strategy that has been impressively unsuccessful.

As for the importance of the data, Williams stresses that we need accurate information gathering, not just to find better ways of policing, but also to look at large public health issues in need of change.

When you go back and look at details of a shooting, Williams said, “there are always antecedent conditions.” Williams pointed to less-than-optimum mental health policies—both at a state and national level—as an example. “It may be the cops who pulled the trigger,” he said, “but it wasn’t the police that were in control of the antecedent conditions” that may have led to the deadly moment. “If we can go back and study these shootings, maybe we can pick out some patterns that show us what we can do to reduce these shootings. But we can’t study them, if we don’t have the data on them.”

If you’d like to listen to the radio discussion that looks at these and other angles of the LE data issue, you can stream the podcast here.