Late last week, a ruling came down from the California Supreme Court that will permanently change the way that the state deals with cash bail.

The heart of the case, originally brought by a man named Kenneth Humphrey, and joined by then Attorney General Xavier Bacerra, among others, is the contention that no person should lose the right to liberty simply because that person really and truly cannot afford to post bail.

The circumstances underlying the Humphrey case began on May 23, 2017, when 66-year-old Kenneth Humphrey, who had fallen off the wagon and was back to struggling with drugs and drink, and was arrested. Humphrey was charged with first degree residential robbery and burglary against an elderly victim, inflicting injury on an elder adult, and for misdemeanor theft from an elder adult.

According to 79-year-old Elmer Johnson, Humphrey followed the older man into his apartment in a residential hotel in the Fillmore District of San Francisco. Then Humprey reportedly demanded cash, threatening to put a pillowcase over Elmer’s head if Elmer didn’t produce some money. When Elmer said he had no money, Humphrey allegedly took Elmer’s cell phone and threw it hard to the floor.

The phone throwing persuaded Johnson to hand over $2. After that, Humphrey allegedly managed to find an additional $5, and a bottle of cologne, both of which he took with him when he exited Johnson’s apartment.

Before leaving, Humphrey moved Elmer Elmer Johnson’s walker into the next room, presumably in order to inhibit Elmer’s ability to report his victimizer.

But Johnson did manage to contact the cops, and Humphrey was arrested.

The $600,00 bail

Humphrey’s arraignment took place on May 31, 2017, at which time, though his public defender, he sought release on his own recognizance (OR), asking that no money bail would be set. His attorney pointed to Humphrey’s advanced age, his community ties as a lifelong resident of San Francisco, and the fact that he had been law abiding for fourteen years.

Yes, Humphrey had four prior felony convictions, some of which were strikes. Yet, the most recent of those convictions was in 1992, a quarter century in the past. And, as mentioned above, Humphrey had no arrests at all for 14 years.

The prosecutor, in response, requested bail in the amount of $600,000 — as well as a criminal protective order directing Humphrey to stay away from Elmer.

The judge dismissed the OR request, and approved the $600,000 bail. Humphrey and his attorney asked for another bail hearing.

Humphrey, who had long struggled with drugs, said he’d been accepted into that a residential substance abuse and mental health treatment program, beginning the day after the date set for another the bail hearing. So, if bail was refused, he would be unable to attend.

At the new bail hearing, the prosecutor argued that Humphrey’s substance abuse issues and inability to address them constituted “a great public safety risk,” and that Humphrey was a flight risk because he faced a lengthy prison sentence based on his prior strike convictions, so he would likely vanish before trial.

The judge reduced the bail to $350,000 bail, which was no easier for Humphrey to pay than the more than half million earlier bail amount.

The discrepancy between the seriousness of the crime and the now still more than a quarter million bail amount caught the attention of the San Francisco’s public defenders office, which was at the time, still overseen by the late Jeff Adachi, who before his death in early 2019, had become near legendary as a gifted justice reformer who was fearless in his defense of the rights of everyday people.

And so it was the PD’s office along with the nonprofit Civil Right Corps, filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus for Humphrey in the First Appellate District of California, Division Two.

Requiring money bail as a condition of release at an amount the accused cannot pay, Humphrey’s lawyers argued, is the functional equivalent of a pretrial detention order — “which can be justified only if the state establishes a compelling interest in detaining the accused and demonstrates that detention is necessary to further that purpose.”

If not, the judge violates the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of equal protection and due process.

Initially, then California Attorney General Becerra opposed Humphrey’s petition. But then Becerra took a hard look at the case and changed his mind. Furthermore, Bacerra stated that his office would no longer defend “ ‘any application of the bail law that does not take into consideration a person’s ability to pay, or alternative methods of ensuring a person’s appearance at trial.’ ” Period. Full stop.

The appeals court sided with Humphrey, and ruled that, since the trial court had not considered whether Humphrey could realistically come up with the required bail, there must be a new hearing, which had to include the defendant’s financial situation.

The trial court conducted the ordered new hearing and, after considering the fiscal variables, ruled that Humphrey could be released, with a few non-financial restrictions, because of his earlier convictions, even through they were so many years in his past. The restrictions included electronic monitoring, an order to stay away from Elmer J., plus an order to participate in a residential substance abuse program for seniors, which Mr. Humprey was agreeable with anyway.

On to the CA Supremes

Meanwhile Humprey’s case moved on to the California Supreme Court, which heard the case in January, and on March 25, affirmed the judgement of the lower court of appeal.

The informatively-written ruling by Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar — with which Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye and Justices Corrigan, Liu, Kruger, Groban and Jenkins concurred — noted that those who are incarcerated pending trial — who have not yet been convicted of a charged crime — “unquestionably suffer a ‘direct ‘grievous loss’ ” of freedom in addition to other potential injuries.”

In principle, the Cal Supremes wrote, “pretrial detention” should be reserved for “those who otherwise cannot be relied upon to make court appearances or who pose a risk to public or victim safety.”

But, “in practice,” the court observed, that’s not what usually happens at all.

So, the Cal Supremes wrote, if the trial court does not consider what an arrestee can pay, money bail becomes “the functional equivalent of a pretrial detention order.”

In other words, it’s the same as the court declining to set bail at all.

Thus, the “common practice of conditioning freedom solely on whether an arrestee can afford bail,” the court concluded, “is unconstitutional.”

And just like that the world of bail changed in the state of California.

(Yes, there are still bail related issues that need to be addressed, and we’ll talk about that in a minute.)

In Los Angeles County, both the county’s public defender, Ricardo Garcia, and the LA DA George Gascón issued statements praising the California Supreme Court’s ruling.

“We are confident that the judges in Los Angeles County will implement this important decision, protecting the rights of presumed innocent Angelenos,” wrote Garcia in an emailed statement. “The front-line lawyers in my office will implement this decision in every case, for every client, in every court, where our clients, many from communities of color, are locked up solely because they cannot post bond.”

Los Angeles County District Attorney Gascón emailed his own statement regarding the ruling, which he said ended “an unjust practice that favors the wealthy and punishes those with limited means.

“We cannot have equal protection under the law,” Gascón wrote, “when fundamental aspects of our criminal justice system hinge so decisively on financial status.”

As for Kenneth Humphrey, since completing the court-mandated residential treatment in December 2018, he has been reportedly staying clean after decades of drug and alcohol addiction.

“Mr. Humphrey not a threat to public safety, he’s an asset,” San Francisco Public Defender Mano Raju told reporters after last week’s ruling.

Since his 2018 release, Raju said, Humphrey had taken on the role of friend and mentor to many in the community who found themselves in his circumstances.

“Mr. Humphrey’s success while out of custody shows what can happen when we invest in people, not cages,”said Raju.

So what’s next?

Despite the importance of the ruling, the struggle over bail in California is not completely over. In January of this year, a trio of California lawmakers introduced bills that would set bail at $0 for all misdemeanors and categories of low-level felonies.

The bills are the latest in a multi-year battle to get rid of the state’s unjust cash bail system.

In 2018, legislators passed and then-Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 10, a hideously watered down bill that would have replaced cash bail with controversial algorithm-based pretrial risk assessments.

The law was scheduled to go into effect in 2019. But then the bail bond industry managed to get Proposition 25 on the 2020 ballot, in order to get rid of SB 10. (A no vote on 25 was a no vote on the passed and signed SB 10)

Last November, California’s voters rejected Proposition 25, and in doing so, got rid of SB 10, much to the relief of most of the state’s justice reformers, who believed that the badly amended version of the bill created more problems than it solved.

The new ruling, in contrast, is viewed by justice advocates as a remarkable step in the direction of banishing cash bail altogether, rather than, as Civil Rights Corps founder Alec Karakatsanis put it, putting “a new facade on the same pretrial human caging, surveillance tech, and wealth extraction from the most vulnerable people in our society.”

So there you have it.

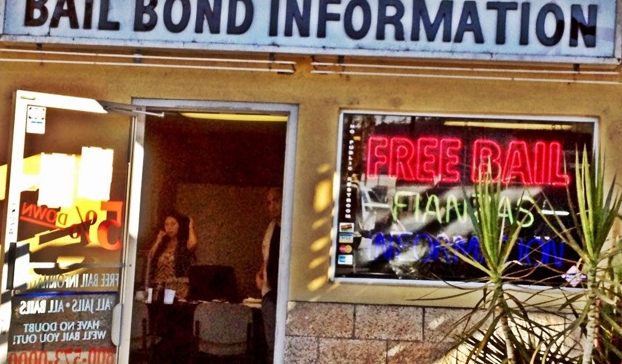

Photo by WitnessLA