by Lindsey Van Ness of Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts

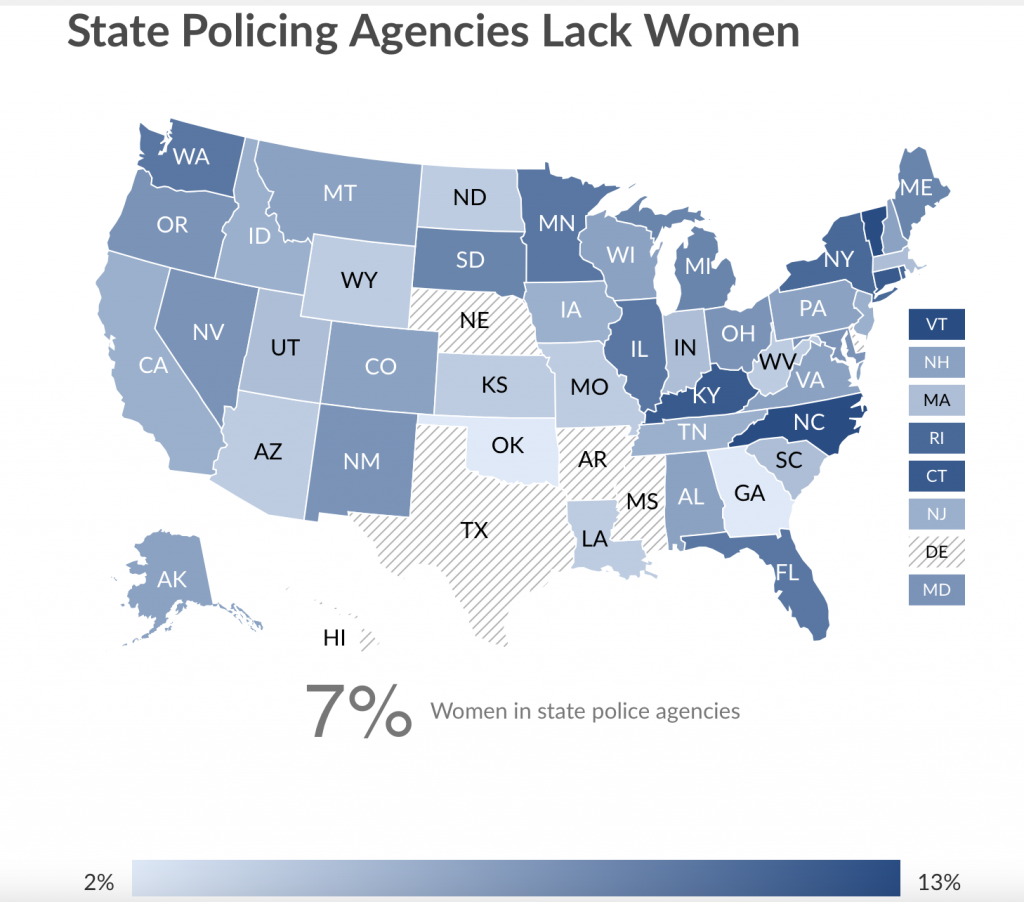

For two decades, amid the rise of women to governor’s mansions, military leadership and even the vice presidency, the percentage of women among the ranks of state police officers has hardly budged: A Stateline analysis finds that nationally, just 7% of sworn state troopers are female.

That’s a tiny gain from 2000, when the average female makeup of state police troopers was 6%, according to a 50-state census by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Overall, women make up less than 13% of full-time police officers in the United States.

As a national reckoning over law enforcement practices unfolds, research shows that women are less likely to use force, are named in fewer complaints and get better outcomes for some victims. Some state agencies are looking to recruit more women to change not only who is doing the policing, but also how their departments police.

“Over the past year I’ve seen a call for a different type of policing. We’ve seen a call for more communication, more empathy,” said Nikki Smith-Kea, an expert on gender equity in policing currently doing a fellowship with the Philadelphia Police Department. “As a profession, are we willing to recognize that having a difference in how we look might have a difference in how we operate?”

Policing experts attribute the low rate of women overall to reasons that include stereotypes about the profession, the demands of training, patterns of sexism and harassment, and the perpetual lack of women to serve as mentors.

All states except for Hawaii have a state policing force, often classified as a highway patrol. In some states, the department is primarily responsible for traffic stops. In others, the agencies also handle criminal cases from all over the state or provide backup to local agencies.

Nationally, just 7% of sworn state troopers are women, according to data provided to Stateline from all but five state policing agencies. That number is a slight uptick from 2000, when the average female makeup of state police departments was 6%, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, contacted every state policing agency, and all but five provided demographic information.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics is conducting another nationwide review of gender breakdown among state agencies, but the data might not be available for a couple years, according to spokesperson Tannyr Watkins.

“Those are sobering numbers,” said Maureen McGough, the chief of staff for NYU School of Law’s Policing Project and a former senior policy adviser in the National Institute of Justice, who this year helped launch a national campaign to recruit more women in policing.

“We’ve known historically that state police agencies have fewer women,” McGough said. “I am surprised to see that the numbers haven’t increased all that much since the last census.”

Meanwhile, most agencies say they want to hire women and have long tried. Although a few told Stateline they don’t have recruiting efforts targeted at women, many more said they are making changes to bring more women on board.

“To better reflect the communities we serve, we need to continue hiring and retaining a diverse membership,” said Vermont State Police Capt. Julie Scribner in an interview.

“Women, troopers of color, LGBTQ troopers—that’s the makeup of our communities,” Scribner said. “The makeup of our department is probably 85% straight, White men. That’s not the makeup of the population of Vermont.”

The benefits

Until recently, the women who worked for the North Dakota Highway Patrol had to follow a few rules: Hair had to be in a bun. No fingernail polish allowed.

Those rules have been loosened to try to add women to the current count: seven of 158 troopers.

One of those women is Sgt. Jenna Clawson Huibregtse. This year, she became the second woman in the agency to be promoted above trooper. Now the 32-year-old is helping lead the charge to bring more women to the ranks.

“Some of the issues we see in law enforcement right now, I think women can help change a lot of that,” Clawson Huibregtse said in a recent interview.

Around 2014, she finished her master’s degree in cultural anthropology and was thinking about joining the military.

“There was a rise in headlines and issues between minority groups and police. And I took issue with that,” Clawson Huibregtse said. “I decided, ‘Well, I think I’m capable of becoming a cop. I want to fix that issue from the inside out.’”

She has found that people relate to her differently than they do to her male colleagues, almost as if they see her as a sister or mother. That helps her in her work: She’s had staff at a jail ask her how she got a man with a violent history into handcuffs, for example.

“Female officers have to use force, that happens all the time,” Clawson Huibregtse said, “but we have a different perspective and a different way of de-escalating situations than sometimes males do.”

A study of the Chicago Police Department published this year in Science found that female officers use less force than male officers. Female officers also are less likely to be the subject of citizen complaints, according to a 2008 study published in the Law Enforcement Executive Forum.

Other research also shows that women are more skilled at assessing the policing needs of diverse communities and get better outcomes for victims of sexual assault.

“For all of those reasons, it’s important to have women as part of the workforce,” said Kym Craven, executive director of the National Association of Women Law Enforcement Executives. “Our country’s demographics is half women. To not have that reflected in policing is passe. We need to come up with the times. This is a job that women can do.”

But getting more women on board isn’t easy.

The Challenges

Illinois state Trooper Omoayena Williams has four kids: a 9-year-old, a 7-year-old and 4-year-old twins. “It’s busy,” Williams said with a laugh in an interview.

She shares her experiences as a mother and a trooper when she meets women in her role as a recruitment coordinator for the Illinois State Police.

Photo provided by Omoayena Williams

“Women, we have to figure out how to balance our career and our families,” she said. “For women, it can be intimidating when you walk into a room and see a lot of men, since it’s a male-dominated profession.”

Williams was born in Nigeria, and her family moved to Chicago when she was 13. She didn’t realize Illinois had a state police department. She was training to join the Marine Corps when she met a state trooper who told her about the agency. She decided to try it, and over the past decade has worked her way up from patrol to recruitment.

Like Williams, many people in law enforcement have a military background, so much of recruiting has been focused there. But women represent about 16% of enlisted forces, so starting from that pool means starting from another male-dominated field.

A lot of agencies don’t do enough to change the perception that state policing isn’t for women, Craven said.

“When you have recruitment videos and recruitment brochures focused on SWAT operations and guns, which is not most of what law enforcement is, it’s not inclusive of women and diversity,” Craven said.

Another barrier specific to state policing is that new hires might be placed at a station, often known as barracks, in a town that requires a lengthy commute or even a move.

“When you apply with a state agency … you don’t know where the vacancies are,” said Charis Paulson, director of compliance and accreditation for the Iowa Department of Public Safety. “When you apply with a city, you know where it is.”

And of course, there’s the rigorous physical exam, which women are slightly less likely to pass. A Bureau of Justice Statistics study of state and local police training academies in 2018 found male recruits completed basic training at a higher rate than females—88% and 81%, respectively.

“Our academy is paramilitary. It is extensive training. It is not only mentally tough but it’s physically tough,” said Carolyn Huynh, deputy chief of training, recruiting and community engagement for the New Mexico State Police.

Compounding the problem is the fact that only 3% of law enforcement leadership positions are held by women, according to Craven of the National Association of Women Law Enforcement Executives. As Smith-Kea put it: “We can’t be what we can’t see.”

Chiefs typically select who gets promoted, said Ivonne Roman, the former police chief of Newark, New Jersey. “It’s difficult when there are so few women, and only a limited amount of women who are mentored to filter up the ranks.”

The solutions

With these barriers in mind, at least five state policing agencies have made a goal to have 30% of their recruits by 2030 be women. Those states (and their current percentage of female troopers) are Illinois (10%), Iowa (6%), Massachusetts (5%), Vermont (13%) and Washington (10%).

The goal comes under the 30×30 Initiative, a collaboration between the Policing Project at NYU Law, the National Police Foundation, the Police Executive Research Forum, the National Association of Women Law Enforcement Executives and others. McGough and Roman co-founded the initiative after hosting a 2018 research summit on women in policing through the National Institute of Justice.

In addition to the state agencies, more than 100 departments from 34 states have signed up since the initiative started in March. The list includes several of the largest agencies in the country: the New York City, Philadelphia and Los Angeles police departments.

The 30% goal was chosen based on the theory of representative bureaucracy, McGough said. “It’s not until you reach 30% that the underrepresented group is able to positively benefit the culture of that group.”

Scribner of the Vermont State Police called the initiative a “no-brainer.” “Why wouldn’t a department sign up for this?”

Her department recently purchased portable pods to give nursing mothers a private place to pump.

In Iowa, the state police agency has started to offer applicants a practice round of the physical exam.

“They know exactly what to expect,” Paulson of the department said, “what it will be like, and can see where they are at and what to work on to be sure they are ready when testing day comes.”

For a few state agencies, recruiting women isn’t a specific focus.

“I think it’s beneficial to have women, but I also don’t want to make it that narrow,” said Lt. Mark Riley, spokesperson for the Georgia State Patrol, where 2% of troopers are female. “I think it’s important and beneficial to have people from all walks of life: females, males, different ethnic groups, religions. You never know who you’re going to come into contact with on the side of the road.”

Similarly, asked whether the Florida Highway Patrol had any recruitment efforts targeting women, Capt. Peter Bergstresser said in an email the agency is “constantly recruiting qualified applicants, regardless of gender or race.” Women make up 10% of the department.

Still, even more agencies said they are taking steps to bring women to their departments.

The Michigan State Police isn’t part of the 30×30 Initiative but has set its own goal of having 20% of its applicant pool be female by December 2022. The agency posts recruitment and staff data on its website. Currently 9% of the agency is female.

The agency has started telling recruits where they will be stationed earlier in the process and tries to keep them close to home, according to spokesperson Shanon Banner.

The New Mexico State Police has taken similar steps. The department, which is less than 8% female, also has added more women to the recruitment team, according to Huynh.

The agency also has revamped its social media accounts, including a new TikTok account, to feature more women.

In the agency’s first video, an officer dons her uniform to the tune of “Unstoppable” by pop singer Sia. The video has been viewed more than 650,000 times since it was posted in March. “It shows the human side of the badge, and it gets the conversation started,” Huynh said.

Back in North Dakota, Clawson Huibregtse said she gets that the idea of being on patrol in the middle of nowhere is intimidating. So is the uncertainty of being posted in an unknown town, not to mention passing through the academy—all challenges heightened for women considering law enforcement.

“From a young age, you’re told what you’re capable of and what you’re not. And so then when you become an adult, you still have those same things instilled in your head,” she said. “At the end of the day, one of our best recruitment efforts is to tell somebody that we believe that they could do it.”

She thinks more women can.

Editor’s Post Script

California’s equivalent of state police is the California Highway Patrol, which did not allow women into its uniformed ranks until 1974.

Flash forward 46 years to 2020, and only 6.3 percent of the CHP’s uniformed officers are women.

On a brighter note, however, on November 17, 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom appointed Amanda L. Ray as the 16th Commissioner of the California Highway Patrol, making her the first woman to lead the Department of more than 11,000 members. Commissioner Ray is also the second Black person in the CHP’s 91-year history to hold the position of Commissioner for the nation’s largest state police agency.

Author Lindsey Van Ness is an assistant production editor and staff writer for Stateline. Previously Lindsey reported on public safety issues at LNP and LancasterOnline in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. She was named Pennsylvania’s emerging journalist by the state’s media association in 2018.

This story was originally published in Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts. All Stateline stories are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Top photo: North Dakota Highway Patrol Sgt. Jenna Clawson Huibregtse stands in front of her police cruiser at the historical Chief Looking’s Village in Bismarck, N.D. The North Dakota agency is one of many state policing departments across the country that want to recruit more women.