At least ten people who could not afford to post bail died in Los Angeles jails without having been charged with a crime, according to a class-action lawsuit challenging the incarceration of people simply because they cannot afford to post bail amounts set by the LA County’s bail schedule.

“Every day, Los Angeles County and the City of Los Angeles confine hundreds of people — people who have not been convicted of any crimes, are presumed innocent, and are not yet represented by counsel—in jail cells based on their inability to pay the arbitrary, pre-set amount of money required for their release,” the lawsuit states. This practice has continued for more than a year and a half after the California Supreme Court ruled in March 2021 that subjecting people to cash bail without considering ability to pay is unconstitutional.

The lawsuit—which was filed on November 14, 2022, by Public Justice’s Debtors’ Prison Project, Civil Rights Corps, Hadsell Stormer Renick & Dai LLP, Schonbrun Seplow Harris Hoffman & Zeldes, LLP, and Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP—names six defendants, the city and county of Los Angeles, as well as the LAPD and Police Chief Michel Moore, and the LASD and outgoing Sheriff Alex Villanueva, as the two agencies “have custody of the majority of arrested individuals in LA County,” and “release arrested individuals who can pay cash bail and continue to detain those who cannot.”

Pre-arraignment bail process in LA County

When someone is arrested in LA County, the arresting agency informs the individual of their bail amount by looking at a “bail schedule,” a chart developed by a panel of LA Superior Court judges listing offenses and corresponding preset bail amounts. The person in custody then can either pay the bail outright, or can pay a bail bond agency a fee usually equal to ten percent of the bail amount.

According to the lawsuit, the ten people who died in jail because they could not afford bail faced bail amounts that ranged between $500 and $100,000, meaning they would have likely had to pay ten percent — $50 to $10,000 — to a bail bond agent to secure their release from jail.

When the person arrested cannot afford to post the presumptive bail amount listed on the court’s bail schedule, they must remain in jail until their first hearing before a judge. While this hearing is supposed to happen within two business days, if a person is arrested on a Thursday, for example, they might not see a judge until the following Monday.

And, of course, even a short stay in jail can result in a host of life-altering consequences, including lost housing, lost wages, termination of employment, and dependent children entering foster care.

Yet, LA has rolled back a zero-bail order adopted in 2020, and has ignored a state Supreme Court ruling that should have significantly reduced the use of cash bail.

Long-promised bail reform yet to materialize

In April 2020, in response to the pandemic and the increasingly urgent need to reduce jail populations, the California Judicial Council implemented a partial zero-bail schedule setting bail at $0 for most misdemeanors and low-level, non-violent felonies. Judges still had discretion to deny pretrial release outright, of course.

This temporary bail schedule expired in just a few months later, at the end of June 2020, and was not renewed. LA County kept its own, very similar version of an emergency bail schedule active at the local level, periodically renewing it before letting it expire in July 2022.

In March 2021, however, more than a year before LA County reverted to the harsher cash bail schedule practices, the California Supreme Court ruled that imposing cash bail without considering a person’s ability to pay was unconstitutional.

Yet, in Los Angeles, as in many other jurisdictions across the state, judicial leaders are failing to do much about the ruling.

In fact, in the year and a half following the CA Supreme Court ruling, UCLA Law and Berkeley Law researchers found no evidence that median bail amounts had decreased in California, and no evidence of a reduction in judges’ use of pretrial detention.

Who remains in jail unable to afford their release?

Of the six named plaintiffs representing the class members in the lawsuit, five were living unhoused when they were arrested. One plaintiff, Daniel Martinez, said he had often lived without housing, but was working odd jobs and living with friends before his arrest.

“Right now I live with friends and contribute to rent however much I can,” said Martinez. “I have been there close to a year, and my housemates and I are a tight-knit community. These friends have also struggled with being homeless and could not post my bond.” Nor could his family afford to pay $2,000 on a $20,000 bail amount, he said.

“I had an interview for a construction job scheduled for yesterday — Friday, November 11,” Martinez continued. “The starting pay was $17 an hour, going up to $22. This job would have meant steady income and the chance to get an apartment. I missed the interview because I am in jail.”

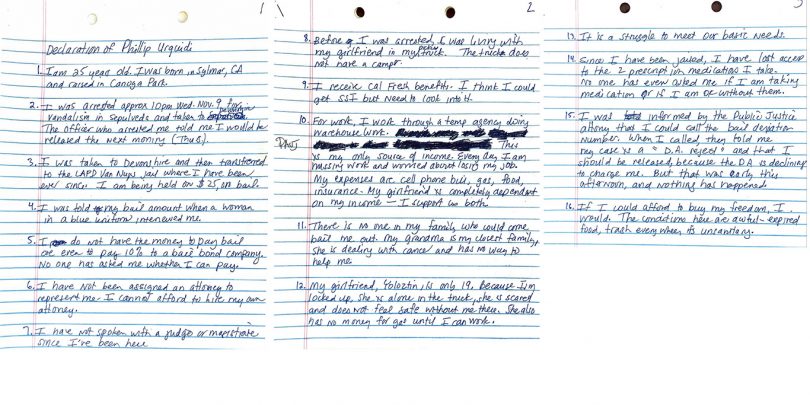

The situation was similarly dire for Philip Urquidi, a 25-year-old who lived in his truck with his girlfriend, and was missing the regular work he received through a temp agency. Because of his incarceration, he said, his girlfriend was stranded without money for gas. “Because I’m locked up, she is alone in the truck, she is scared and does not feel safe without me there.”

Another plaintiff, 37-year-old Terilyn Goldson, a former paralegal, had been living in tent communities since she was evicted in June 2022.

Goldson, a mother of two young children who live with their father, said she missed a chance to see her children because of her incarceration.

When she wrote her declaration for the lawsuit on November 13, 2022, Goldson had been incarcerated for five days, and said she still did not know what she had been arrested for, or what charges to expect.

Goldson had been informed that her bail was set at $75,000, leaving the possibility of release far out of reach. “I can’t even afford to pay a bail bond company a fraction of that amount,” she said. “I have family members who love me — my grandma, my dad and my aunt — but that is so much money I can’t imagine how they would be able to help me.”

At the time the plaintiffs wrote their declarations from inside city and county jails, none had been asked whether they could afford to pay their bail amounts.

“If two people are arrested for the same alleged crime, a person who has money can pay to immediately go free while someone without the same resources is confined in a jail cell for days before they get a lawyer or see a judge, “said Brad Brian, Chairman of Munger Tolles & Olson LLP, one of the firms representing the plaintiffs. “The result is that on any given day, instead of going to work or being with their families, hundreds of people remain in jail solely because of poverty. This needless deprivation of liberty also makes us all less safe because it costs people jobs and housing and destabilizes their lives.”

I’m sorry Taylor, but I’m not feeling bad for any of these people in your story. You tell us their whole story about missing a job interview because one was in jail and that interview would’ve changed his life forever. Ok…what did he do in order to get arrested?

Buddy Behrens Is Judgemental And Disregards Constitutional Rights. We Don’t Need Him.