by Isaac Ceja and Lauren DeLaunay Miller

A young woman, 19, sits in a director’s chair and watches as her face reflected in the mirror slowly transforms. Her eyelids are now varying shades of purple and her lips, a deep magenta.

She closes her eyes from time to time and remains still while the makeup artist works with the precision of a Renaissance painter, using different brushes, sponges and colors to complete her work of art. Here, in the basement of a large conference space near downtown Los Angeles, the two young women are experimenting with healing and forming community in unconventional ways.

On this day in early December 2024, the two women, who requested that their names be withheld due to their immigration status, are at a gathering with dozens of other immigrant children and young adults in downtown Los Angeles hosted by an organization called Community Justice Alliance. Founded in 2018, the organization specializes in representing unaccompanied children that have come to the U.S. without a parent or guardian.

Helping migrant children adapt

More than 10,000 unaccompanied youth have entered California each year since 2020, most of them leaving violence or insecurity in Mexico and Central America. After arriving in the United States, their paths differ, but the majority are held temporarily by Customs and Border Protection before being released to extended family members or foster homes.

After release, these children often seek legal aid to fight deportation orders, request asylum or file claims for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, a legal status that protects youth who have been abused, abandoned or neglected. Community Justice Alliance provides legal aid but has also realized that the children they represent need more than that. The majority of the children have suffered from trauma and need mental health support. Many also need help connecting with schools, medical providers, health insurance and language education.

Something else Community Justice Alliance staff noticed is that many of their clients feel alone in their experiences and don’t feel safe sharing them with others in their new communities. So, in the last few years, the organization began hosting events where their clients from across the state could get together to connect in their shared experiences and with peers from their home countries. Events range from soccer meetups to visiting iconic California landmarks like Yosemite National Park and Disneyland, providing an opportunity for participants to heal by spending time with other unaccompanied minors.

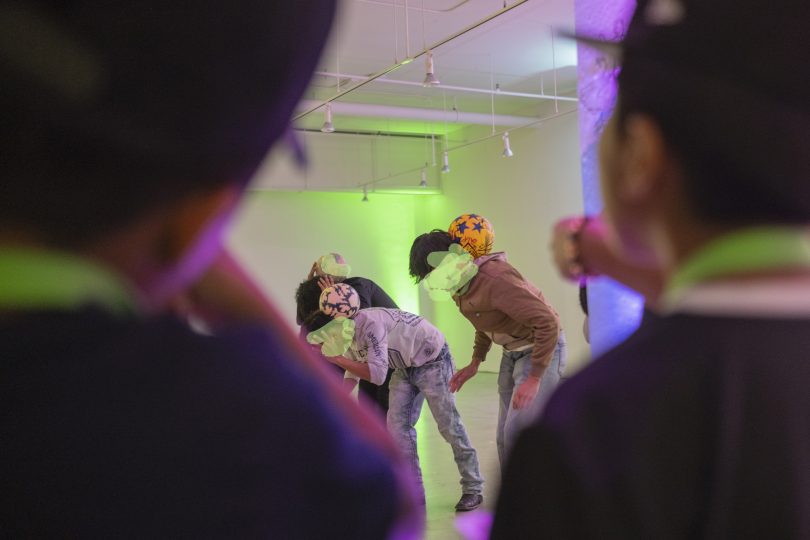

Jessica Emigdio, the alliance’s youth mentor, spent months meeting weekly with the organization’s clients, learning about their needs and interests. She drew from that information to plan activities for the conference center event in December, which brought together more than 40 young people ages 11 to 22. In addition to the makeup demonstration, there was a poetry workshop hosted by local Salvadoran-American poet Yesika Salgado, a sound healing experience, and a hangout area with bean bags where a huddle of boys played FIFA soccer video games on a big screen TV. A crowd of teenage girls surrounded the makeup artist as she demonstrated her wide-ranging skills, choosing from a rainbow palette to match each girl’s requests. Her work seemed effortless, but it was the result of a love affair with makeup that has spanned more than a decade.

A teenage makeup artist’s journey

The makeup artist, who we’re calling Elena to protect her identity, fell in love with makeup when she was 7 years old. While her mother was at work, Elena would sneak into her mother’s makeup stash, trying on the cosmetics before anyone could see. At age 15, she enrolled in beauty school to pursue her passion and eventually became well known for her artistry in her hometown of El Aguaje, in the state of Michoacán, Mexico, she said. Makeup was not just a passion but a way to express herself. “It feels like you can pour out your emotions and free yourself like birds in cages that want to escape and be free,” Elena said.

Despite her successes, the makeup artist said she dealt with the dangers of living in a town where cartels fought over control of the area. The most recent Mexican census data from 2020 showed that only 2,550 inhabitants of the 15,000 that had lived in El Aguaje in the 1990s remained.

When Elena was 17, she left with her brother and 22 other relatives. Her parents stayed behind.

At the U.S. border, Elena and her relatives were handcuffed and questioned. Once they said they were seeking asylum, all were let go except for Elena and her brother because they were considered unaccompanied minors. The two siblings remained in custody at the border for eight days until other relatives, who were U.S. citizens, agreed to take them in.

Elena and her brother settled with extended family in Fresno. A few months later, their parents were able to join them in the U.S. At first, things were great: they were safe, and together. But two years into her life in the U.S., the difficulties of adjusting to life in a new country caught up with the teenage girl. She struggled to process what she had been through. Her makeup supplies, she said, sat on a shelf, gathering dust.

Reclaiming identity

Community Justice Alliance Executive Director Kristina McKibben-Sias said that while there is not a lot of health data on unaccompanied youth specifically, her experience has shown her that “we are just barely starting to scratch the surface in understanding their integration experience.”

McKibben-Sias and her team have found it helpful to integrate the framework of Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, when they are working with unaccompanied youth. ACE scores are calculated based on a 10-question survey and ask about abuse, neglect and household dysfunction faced as a child. According to McKibben-Sias, almost all the youth they work have high scores, which can put them at increased risk for a number of long-lasting health impacts like chronic diseases, substance dependency, intimate partner violence and even early death. Unaccompanied minors “are at risk of psychological stress and consequently may develop symptoms of anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress,” according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

And yet, McKibben-Sias has hope. “Something we have learned from the young people we work with is how elastic mental health support can be,” she said. In addition to professional mental health care, the organization has recognized that their clients need youth-led healing opportunities as well. “Just like any of us, many are searching for a space where they can relax their shoulders,” said McKibben-Sias. “Not a space where they have to explain their journey, but a space where they can play. A space where they have an artistic and spiritual outlet.”

When deciding what activities to include in last December’s gathering, McKibben-Sias hoped that showcasing artistic expression could help other young people explore their creativity.

“Makeup is more than cosmetics,” Emigdio said. “It’s a form of control in an unpredictable world. For youth who have experienced trauma, experimenting with makeup offers a safe way to reclaim their identity and express emotions without words. It fosters confidence, creativity and self-discovery, helping them process their experiences in a deeply personal way, regardless of what language they speak.”

Back at the makeup stand, Elena and her young client look at each other in the mirror and smile.

“It was incredible,” the teenage customer said after. “No one’s ever done that for me.”

“Beyond self-expression, makeup creates community,” Emigdio, the youth mentor, said. “Sharing beauty routines builds trust and connection, allowing youth to bond over something positive rather than their struggles. In a world where they often feel invisible, makeup provides visibility — allowing them to be seen on their own terms.”

****

Author Lauren DeLaunay Miller is an award-winning author, journalist, and audio producer based in California. (Her first book is the prize-winning Valley of Giants: Stories from Women at the Heart of Yosemite Climbing.) As part of the California Local News Fellowship at UC Berkeley, Lauren reports on rural health equity and the Eastern Sierra for California Health Report.

Author Isaac Ceja is a Mexican-American documentary photographer and journalist based in Southern California. He says he is shaped by “experiences growing up just a block away from Disneyland as part of a family of immigrants and spending several summers in Ensenada, Baja California in Mexico.”

NOTE: This important and very timely story is cross-published with our friends at the California Health Report. The story was created as part of the Solution Journalism Network’s HEAL Fellowship on youth mental health.