Violence & neglect in California’s prisons for kids: The 1st in a series

“It did not want to make people build their dreams. It did not rehabilitate me, for sure. If anything it made me worse.” DJJ youth graduate

When a California youth is sent to a locked juvenile facility, in most cases he or she will be sent to a juvenile hall or camp located in his or her home county.

This has been the case since 2007, when then Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed SB 81, also known the “Juvenile Justice Realignment” bill, an important piece of reform legislation that limited the reasons why a kid could be sent to a state youth correctional institution. SB 81 was based on, among other things, the mounds of research showing that, with the right programs and help, young people who land in the justice system have better outcomes if they are supervised closer to home.

Now, in Los Angeles County, of course, as in other progressive California counties, the goal is to prevent and/or divert the state’s children from being locked up at all.

Yet, despite the changes that SB 81 ushered in twelve years ago, approximately 650 youth and young adults from across California, are sent away from their home communities to one of three facilities run by state’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), which is overseen by the the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. These are the state’s youth prisons.

In the last five years, Los Angeles County alone has sent between 108 and 161 kids a year to DJJ, according to LA County’s probation figures:

2014: 106

2015: 147

2016: 161

2017: 138

2018: 128

During those same five years, WitnessLA has spent a lot of time reporting on LA County’s juvenile facilities and programs. But what about those of the state?

A new and alarming report released Tuesday by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice provides a comprehensive review of conditions in the youth facilities run by the DJJ.

What the authors found was a disturbing climate of violence and fear that breeds trauma in already traumatized youth, and where a recent spike in attempted suicides and high rates of youth injuries, are among the indicators that raise urgent red flags about kids’ emotional and physical safety inside DJJ’s three aging facilities.

The bad past

In order to understand present conditions at DJJ, it helps to know a bit about its past.

Northern CA DJJ facilities known as Chad and O.H. Close occupy a joint campus near Stockton in San Joaquin County

It’s important to know, for example, that today’s 650 youth population figure is a 93 percent reduction from the bad old days of the mid-1990’s through to the early 2000’s, when DJJ—formerly known as the California Youth Authority, or CYA—housed as many as 10,000 young people, and was plagued by a mind-numbing level of controversy and scandal that included a wave of youth suicides and graphic reports of horrific staff abuse.

Finally, in November 2004, a consent decree was ordered as part of the settlement of a lawsuit, Farrell v. Harper, which detailed nightmarishly unconstitutional conditions in the CYA facilities, and laid down a list of mandated reforms.

The core requirement of the Farrell agreement was that CYA must exchange its abusive, and viciously punitive system for a rehabilitative model of working with kids. Theoretically that was gradually accomplished.

Thus, finally in early 2016, the state’s youth system—that has now been renamed the Division of Juvenile Justice—was deemed to be sufficiently reformed to be released from its 12-year consent decree.

So how reformed is DJJ really? And how well has the system done since 2016, now that the mandated monitors and the glare of public spotlight has gone away? After having fifteen years to fix things, how has the state done?

“By placing youth in prison-like conditions at large institutions, DJJ exposes them to the trauma of incarceration, risking their immediate safety and limiting the possibility of rehabilitation.”

According to Tuesday’s 102-page well-documented report, fifteen years after it got slammed with the consent decree, and nearly three years since the court monitors packed up and went home, the DJJ has somehow not managed to solidify reform. Worse, it “has returned to its historical state of poor conditions, a punitive staff culture, and inescapable violence.”

In anticipation of the report, Unmet Promises: Continued Violence and Neglect in California’s Division of Juvenile Justice, co-authored by Renee Menart and Maureen Washburn, WitnessLA did our own research, including speaking with kids who have recent experiences with DJJ, along with various knowledgable adults, including a DJJ staff member, all of whom gave us additional details about the issues that the report describes.

And the news is not good.

Higher budgets, and dangerously high levels of violence

“Intake is the most dangerous place in DJJ. That’s where most of the fights happen because people are from different neighborhoods…That place is known for riots.” – DJJ youth

Although the numbers of youth in the DJJ’s remaining three aging facilities (and one conservation camp), have steeply declined, the amount the state spends on each kid per year increased between FY 2012-13 and FY 2017-18—jumping from $208,000 per year per youth in a DJJ facility, to $315,000 per youth per year by 2018.

But despite the rising dollar amount spent per kid, and the introduction of supposedly better and more rehabilitative programming, according to Washburn and Menart’s report, violence in the facilities has gone back up precipitously now that the monitors are gone.

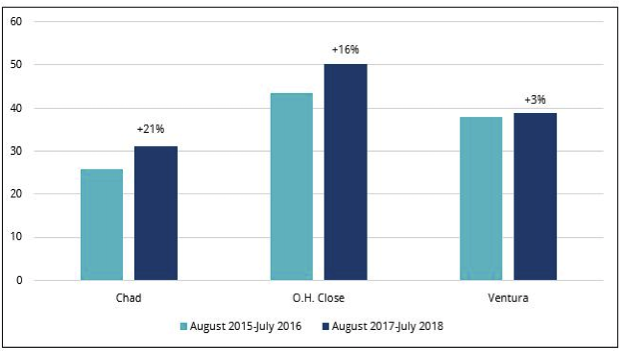

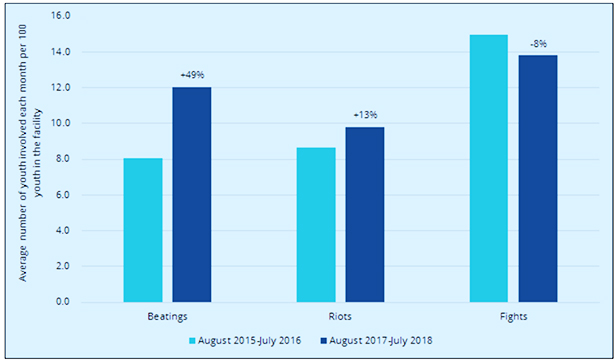

Since the end of Farrell lawsuit oversight, an average of 33 youth per 100 in the DJJ population were directly involved in a violent incident each month, and the rates of riots and beatings have also shot up according to the report.

Change in the average number of youth involved in a violent incident each month, per 100 youth in the facility, August 2015-July 2016 vs. August 2017-July 2018

Inappropriate use of force and “gladiator fights”

“Literally the day after Farrell ended, guards were bragging about going back to the good old days.” –DJJ Staff

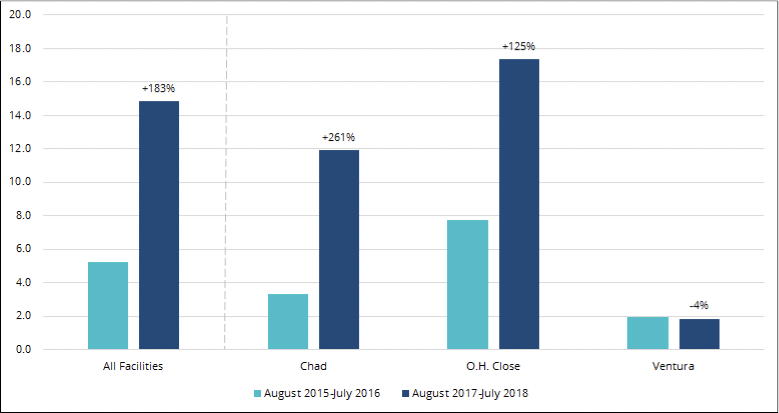

The use of force by DJJ staff, has also increased three-fold, according to the report, as compared “to the one-year period during which the Farrell lawsuit was dismissed.”

Every kid they interviewed, the co-authors wrote, could describe an “inappropriate use-of-force incident” that he or she had witnessed or experienced.

The incidents the youth described included having their legs kicked out, “or being placed in a headlock during a strip search and being physically assaulted by staff while handcuffed,” and other equally inappropriate actions. In addition to incidents directly witnessed by youth, several kids and staff described rumors about staff beating youth in transport vans or in unseen corners of a facility, including the ice machine areas in one of the units.

Whether the rumored beatings occurred or not, matters regarding youth violence and staff use of force are not helped by a surprising lack of surveillance cameras in the three main facilities, which are located in Ventura County in Southern California, and two in Stockton, in the northern part of the state.

Change in the average number of use-of-force incidents each month, per 100 youth in the facility, August 2015-July 2016 vs. August 2017-July 2018

For instance, one of the Stockton Facilities, known as “Chad,” only has cameras at the exterior entrances of each unit and at the main security gates. Living units, kitchens, and dining rooms have zero cameras, the authors noted during one of their tours.

Similarly, an administrator at the Ventura facility remarked to the authors that there are “virtually no cameras throughout the facility,” and some of the few cameras present “are not functional,” he reportedly told them.

Obviously, this means violence between kids, or by staff, can easily take place in secret.

In 2018, when the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) released a report on use-of- force incidents across all CDCR facilities, adult and youth both, the OIG identified the school area of one of the Stockton facilities, as the site of the “eighth most use-of-force incidents in the entire California prison system,” placing it on par with maximum security adult prisons.

The OIG’s analysis of force incidents also found that DJJ was out of compliance with use-of-force policies at higher rates than was found the state’s adult prisons, according to Menart and Washburn.

And that was the force that the OIG’s investigators were aware of.

Both kids and staff members told the authors in one-on-one interviews about force incidents and other staff misconduct they had experienced or witnessed that didn’t get reported, such as instances when staff members arranged fights between youth, including one such “gladiator fight” incident” involving Norteño and Sureño youth in the Chad school area and another in the showers.”

In other interviews with staff and kids, the authors heard about a seemingly endless variety of alleged “acts of disrespect” by staff members, including such demeaning, but reportedly common incidents as when staff “would toss a youth’s cell while they were in the shower,” or would “destroy or confiscate their papers or photographs,” or “give arbitrary write-ups” on a Friday with the knowledge that the youth was expecting a visitor that weekend, “hindering their ability to visit with loved ones.” And so on.

Injuries, suicide attempts, and withholding needed medication

It would seem to be obvious that good quality medical care and mental health services are critical to the overall health of youth housed in the care of any California county or the state.

But according to the new report, since the dismissal of the Farrell lawsuit in February 2016, there has been a series of barometers suggesting cause for concern, such as the 28 attempted suicides in the DJJ facilities, 20 of which occurred at the Ventura facility located in Camarillo, CA.

The authors were also concerned that DJJ facilities reported a total of 1,338 injuries to youth—which is about three injuries per day—from June 2017 to June 2018. Of those injuries, about half were caused by other youth and 51 required outside medical attention.

Kids also described experiences in which their medical needs went unaddressed, including delays in seeing a nurse, genuine symptoms being dismissed, misdiagnoses, and the failure to provide needed medication.

An attorney for one youth told the report’s authors how her client who was prescribed a psychiatric medication prior to his arrival at DJJ, was not allowed that medication during the “intake” period.

(“Intake” is an evaluation process that lasts approximately 45 days, during which time youth are introduced to DJJ rules and procedures and undergo a battery of assessments.)

“Even after transferring to his permanent living unit, the client reported that he could not receive medication “because he had failed to file a formal request,” stated the report.

It didn’t seem to matter that “requiring any youth with mental health needs to advocate for their own medication or treatment defies best practices,” the authors added grimly.

In addition, stated the report, “DJJ’s mental health care model focuses on the acute needs of a small population of youth, while disregarding the [needs of the] broader population and the benefits of therapeutic programs.”

Counterproductive behavior management that uses family visits and phone calls as weapons

“When I came out, I was different.I couldn’t have conversations with people, even with my family. I felt cut off because they isolate you.” – DJJ youth graduate

There were other serious issues that the authors outlined in their report, such as an often substandard educational system, and the observation that “very little programming exists at DJJ beyond school and work,” resulting in excessive idle time that, unsurprisingly, often contributed “to violence and negative health impacts.”

The authors also described “deficiencies” in the DJJ facilities’ overall “behavior management system,” which, rather than helping kids change unwanted behavior, interrupt gang conflicts, and begin to heal childhood trauma, used methods that seemed to be arbitrary, at best, in their application, according to the report.

Furthermore, the authors wrote, the system featured a system of “incentives,” that appeared to leave the vast majority of young people in the facilities “excluded from the basic comforts and activities” that should have been automatically provided to all, not doled out as rewards only available to the highest achievers.

This included normal mattresses rather than prison bed pads—and, even less appropriately, family visits and phone calls.

We know beyond dispute that, for adults who are locked up, healthy contact with family is one of the prime predictors for success when those adults get out. That rule is even more crucial when it comes to kids, for whom opportunities to meaningfully engage with family members are vital to their well-being, both while they’re at DJJ, and when they go back to their communities upon release.

Yet, according to Washburn and Menart, family visits and phone calls seems often to be made unnecessarily difficult for kids in DJJ.

“Among the youth and family members interviewed for this report, nearly everyone remarked on the challenges and limitations they faced when trying to stay connected,” wrote the report’s authors.

Part of the problem for many youth, was the distance their families lived from each of the DJJ facilities.

And some kids simply don’t have supportive parents who are willing to visit, meaning family dysfunction is one of the challenges they face.

But there are other barriers, according to the report, and what we heard in our follow-up research—namely that staff used access to visits and phone calls as part of their system of sanctions and rewards.

According to the DJJ’s system, a youth’s access to visits often depended on what was known as their “behavior phase.” In other words, it is the practice at DJJ “to treat contact” between a kid and his or her family as “an incentive for good behavior rather than an asset in the youth’s development.” (WLA’s italics.)

At the northern facilities, wrote the authors, youth who have maintained an above average program—aka behavior— (known as A Phase) are allowed to receive visits on both Saturdays and Sundays for the full visiting period. But, from there, the opportunity for family engagement stair-steps down for youth who have not worked up to “A Phase,” or who have worked up, but then gotten a “write up” that drops them down again to another “phase.’ For instance, kids in “D-Phase,” are only allowed visitors one day per weekend, and if the family member can’t come that day, well….tough.

Visiting opportunities are most restrictive when youth are assigned to the lowest unit, where “they may be allowed shortened visits by appointment only.”

A similar system applies to phone calls:

In addition to letter-writing, kids are entitled to four 10-minute collect calls to family each month—or one per week. Local calls cost about three cents per minute and interstate calls cost about 13 cents per minute.

Since those costs (which rake in a tidy profit for Globel Tel Link, incidentally) can weigh heavily on low income families, kids are allowed to make one additional call per month for free at DJJ, termed a “direct call,” but the number and length of such calls differs widely depending upon the kid’s category.

Youth on “A Phase” are allowed a 20-minute call, youth on “B Phase” are allowed a 15-minute call, and youth on C or D Phase are allowed one 10-minute direct call to a support person each month.

As with DJJ’s visiting policy, “this practice for direct calls actively separates youth on lower behavior phases from the support of their families,” note the authors, “leaving those who are going through the most serious challenges with only ten minutes to connect with a family member for free each month.”

Enter The Governor

As many WitnessLA readers likely know, the new report has arrived at a timely moment.

In January, Governor Gavin Newsom announced his intent to move DJJ away from California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and place it instead under the control of “government health and human services providers.”

Youth advocates have praised the idea.

Yet, many of the state’s probation chiefs and other law enforcement professionals were not so sure. The change could endanger “the great movement we have made in juvenile justice over the last decade,” said Stephanie James, president of the Chief Probation Officers of California, who also cited ” historic levels of investment in evidence-based programming for youth.”

When it comes to DJJ, however, the new report and WitnessLA’s research failed to find such “great movement.”

The recidivism problem

“Staff exercise their power like, ‘I can keep you here longer. You better respect me, you better listen to me.’ They should be preparing us for when we get released.” – DJJ youth

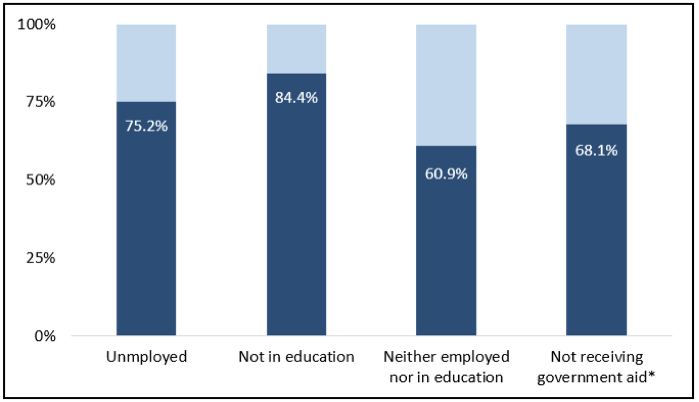

In fact, among youth returning home from DJJ, recidivism remains high, and other outcome measurements are not encouraging either .

According to the new report, most recent available data shows recidivism outcomes for 675 youth released from DJJ in fiscal year 2011-12, and follows them over a three-year period. During those three years, 74 percent of the youth were arrested, 54 percent were convicted, 40 and 37 percent were returned to state-level incarceration including DJJ and adult institutions . Of the youth who were ultimately sent to state-level correctional facilities, 64 percent had returned within 18 months of their release from DJJ.

“Reentry is a process that should begin upon a youth’s arrival in out-of-home placement rather than as a youth’s release date nears,” stated the report. That process should included elements such as family engagement, preparation for employment and/or continued education, and eventual connection to useful community programs.

Instead, DJJ’s haphazard approach to reentry planning and lack of collaboration with community-based groups and programs upon release shows the institution’s failure at rehabilitating youth for their return to the community, wrote the authors.

Their point was illustrated by a survey of 14 counties representing 41 percent of the DJJ population, including Alameda, Kern, Merced, and Sacramento counties.

In June 2018, 61 percent of youth under these counties’ supervision were neither employed nor enrolled in an educational program after release from DJJ, and few received any government support to meet their basic needs.

The resulting high recidivism rates among DJJ-impacted youth point to “institutional shortcomings” that show placement in DJJ’s care fails to result in positive outcomes for the kids it serves, wrote the authors.

“This report comes at a time when California is at a crossroads,” co-author Renee Menart told WitnessLA. “We can continue to invest $200 million per year in a historically harmful institution, or we can work together to transform our juvenile justice system to truly support the needs of youth, their families, and communities.”

Some youth advocates are cautious, concerned that any perceived weakening of DJJ may give local prosecutors around the state an excuse to push youth into California’s adult prison instead of the imperfect state juvenile system, which—for all its flaws—they say is still the far less damaging choice .

But Menart and co-author Maureen Washburn see another possible future. “The Governor’s budget offers an opportunity for the state to reimagine juvenile justice and reduce reliance on these archaic institutions,” she said. “To ensure that all youth receive trauma-informed care that prepares them to return home healthy and whole, the state must begin phasing out the DJJ facilities and maximizing the substantial capacity already available for youth in local, close-to-home settings.”

Next we’ll have some personal stories from DJJ in part 2 of this series, so….stay tuned.

While agreeing with the author that the outcomes in our Juvenile Justice System are terrible, consider the information provided (Swiss cheese like) verse needed (three cheese finely grated and thoroughly mixed) in order to get a good look. The author show parts but not all. With not discredit to the author, there are macro issues that make this presentation less than what is needed for designing effective answers, and in agreement with this author, this discussion should be about implementing interventions which work, change thinking and behavior and in the end save young lives. So what is missing?

First, consider the role and impact of gangs within the State and County lockup facilities as a paramount factor to accomplishing anything. Gangs control much of the culture and activity within the lockups and are unavoidable. When we send non-gang youth into state or county lockups, they are immediately harassed until they agree to join one or another of them. Then their lives get worse, because they are now ‘fodder’ for the gangs to use at their whim (hit a guard, beat up that kid, pick a fight with that big guy, hold on to these drugs, etc.) Our County and State lockups are flat out gang recruiting centers. Effective treatment for gang members and non-gang members can be quite different. And yes, there are effective treatment interventions for Gang Youth. Fear of beatings, rape and death can create real focus for anyone, especially youth. Non-gang members are more concerned for their lives and doing all possible to keep away from the different gangs beating them up, ‘again.’ Their lives are threatened as are their family member’s lives. What would you and I be focused on in this situation? How well can we work with the non-gang youth to consider the reason for their actions which got them into our lockups when their thoughts are on keeping themselves safe? No too likely, is it? Great outcome prospects, huh?

Second: Systemic Approaches – When we don’t use outcome based approaches, but instead use politically based approaches (Ex: California) and state dictates to services, it is no wonder that our outcomes fail. Does anyone ever wonder why other states have very different outcomes with their troubled youth? It is because they design one system that integrates approaches from the first contact to the worst case youth’s best outcome. Systematic approaches filled with best practices and proven outcomes for each stage of the youths determined immersion into the system work. As the youth moves deeper into the system (one stage at a time), the progressive interventions build on each other and when one stage finally works for the youth, the same system backs the youth out of the system and back into their home. For clarity, I’ve seen it work again and again, and while not perfectly, it did changes a lot of youth and their families. As great as California is, one of Achilles heels is that we think that we can’t learn from others, especially smaller states. We miss so much with this view of ourselves and the world around us. Shouldn’t we ask why we have so many Human Services/Prison related Class Action Lawsuits, and services systems focused by the state on ‘adequacy’ instead of excellence?

Third: Behavioral Health Services (Mental Health) – Where other states have layered systems for keeping children and youth safe (yes they start their intervention system with children), treating them and their families, and working youth into and out of their behavioral health services, we don’t even have a system to compare with. We have failed when it comes to home based family services, school based services, intervention services, partial days services, hospital based services and etc. They use the County Health Department’s services (early identification and intervention) , Youth Services agencies (nonprofit), Mental Health agencies (non-profit), DHS-Child Services (case workers), Department Juvenile Services (Case Workers) all before taking the child out of the community or locking them up. There is more, but it cannot be addressed in this brief forum.

Now for my admission:

1. There is a place in the system where criminally violent youth need a locked/secure environment. We must keep youth from hurting themselves and others.

2. Some youth’s behavioral health issues require a secure setting for days or months, both to keep them safe and to make vital therapeutic progress.

3. Sometimes a broadly secure setting is needed for constant runaway.

But in each of these three distinct setting specific programs and behavioral health interventions are paramount, with individual goals and expected outcomes.

I can’t address the entire package of grated and mixed cheese in this simple response. But be assured that it is a very good product with wonderful outcomes, and while not perfect, it is far better than anything even dreamed of within California.

Please be assured that we can do so much better than we are and can see youth’s lives changed for the good every day.

Great analysis

[…] DJJ facilities since the end of the Farrell oversight period in 2016, found that an “average of 33 youth per 100 in the DJJ population were directly involved in a violent incident each month.” Adding to the […]