LOS ANGELES-AREA SCHOOL DISTRICTS REDUCE TRUANCY FILINGS AND CUT SUSPENSIONS, BUT PROBLEMS REMAIN

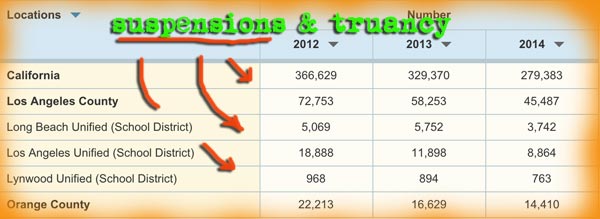

School districts in the Los Angeles region are reducing suspensions and are citing fewer students for truancy, moving away from harsh punishments that keep kids—often the ones who need the most support—out of classrooms, and toward restorative justice models.

The statewide numbers dropped, too. Overall, California schools handed out 12.8% fewer suspensions during the 2014-2015 year than the previous year.

Lynwood Unified has emerged as a role model to other school districts for reducing willful defiance suspensions from 543 in 2013-14, to 183 in 2014-15. The district, which is located in South LA, also reported a truancy rate less than half the state average in 2013-14.

And in Orange County, Superior Court Judge Maria Hernandez, who presides over the juvenile court, overhauled the county’s punishment-focused truancy system in 2012. Youthful offenses, including truancy, are often kids’ responses to deeper issues like trauma or a troubled home life. Hernandez created a truancy response team made up of social workers, probation officers, and other people to respond to the needs of chronically truant kids and their families.

While districts lowered the number of citations for truancy, actual truancy—three 30 minute (or more) instances of unexcused out-of-class time—actually rose by more than 90,000 in California during the 2013-2014 school year over the previous year. This uptick may be due to schools implementing better attendance-tracking practices.

But while the state numbers rose, Long Beach Unified succeeded in lowering its chronic absence rate from 26.2% in the 2013-14 school year to 9.6% last year, following a district-wide push to educate parents about the long-term negative impacts chronic absence and truancy can have on students’ achievement and future.

Long Beach also cut its suspension rate by over 800 last year. Unfortunately, black Long Beach kids, who make up 14% of the student population, are still far more likely to receive suspensions than their peers. They account for a third of LBUSD suspensions. And while the district has greatly reduced the number of suspensions given for the catchall “willful defiance,” teachers are still removing disruptive kids from classrooms without formally suspending them.

Nadra Nittle has the story for The Chronicle of Social Change. Here’s a clip:

The California Attorney General’s Office posits that the uptick in the state truancy rate likely stems from schools improving how they monitor student attendance. It points to Long Beach Unified as a district that managed to lower its chronic absence rate, even as truancies rose.

LBUSD lowered its chronic absence rate from 26.18 percent in the 2013-14 school year to 9.6 percent the following year. The district of nearly 80,000 students credits the drop in chronic absences to parent outreach and to school officials scrutinizing district data to pinpoint the schools with the most absences.

“There were about 30 elementary schools with pretty poor attendance rates and high truancy rates,” said Erin Simon, director of LBUSD’s student support services division. “I spoke with the school staff and most importantly with the parents and the families about high chronic absence and chronic truancy.”

Simon discussed with families the consequences of truancy in kindergarten and first grade, including how it results in 83 percent of students being unable to read on grade level by third grade.

Long Beach Unified also expanded the reach of its School Attendance Review Board (SARB), a group made up of school officials and community members to curb absenteeism. The district was named a 2015 Model SARB district for its efforts to reduce school absences.

SOLITARY CONFINEMENT AT PELICAN BAY STATE PRISON

Pacific Standard Magazine’s Jessica Pishko visited Pelican Bay State Prison’s Security Housing Units (solitary confinement).

Back in September, California settled Ashker v. Brown, drastically limiting the use of isolation in state prisons. The lawsuit was brought on behalf of a group of ten Pelican Bay State Prison inmates who had spent at least 10 years in solitary confinement each.

(The plaintiffs led the prison hunger strikes of 2011 and 2013 protesting the conditions of solitary confinement in California prisons.)

Pishko takes a look at the “step down” program for inmates leaving the SHUs to reenter the general population, and wonders how the men will adjust after years in isolation. “How will these men adjust to a bustling prison yard when they haven’t even touched another human in decades?” Pishko writes. Here’s a clip from Pishko’s story:

This Ashker settlement comes on the heels of a steadily increasing drumbeat against indeterminate solitary confinement, as everyone from the DOJ to the United Nations has come out in opposition to the penal practice. In the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Davis v. Ayala, a California death penalty case, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that “research still confirms what this Court suggested over a century ago: Years on end of near-total isolation exact a terrible price.”

Releasing a group of inmates who have been touted for decades as “the worst of the worst” back into the prison mainstream can’t happen all at once. In an effort to unravel longstanding policies of extreme confinement, the CDCR has instituted the Step Down Program, which relies on a behavior-based model to allow inmates to graduate through five steps, each of which grants greater privileges, including phone calls and visitation. The program culminates in a release from SHU housing entirely. The idea is to slowly phase out long-term SHU housing, and release solitary inmates who follow all the rules back into the general prison population.

But how will these men adjust to a bustling prison yard when they haven’t even touched another human in decades?

[SNIP]

The effects of solitary confinement have been proven to be psychologically and physiologically damaging. In connection with the Ashker case, Dr. Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist and expert in solitary confinement, filed a report in March of 2015 describing what he called SHU Post-Release Syndrome, a series of symptoms including “a sense of being overwhelmed by sensory stimulation, massive anxiety when in crowded places, hyperawareness of every noise or change in lighting, a tendency to seek isolation in contained spaces, and difficulty expressing oneself in close relationships” that only emerge after getting out of the SHU. Pelican Bay inmates reported the same feelings— almost a complete alteration of their personality—whether they were paroled or sent to the Step Down Program.

“People who have been consigned to solitary for many years feel inclined to isolate themselves after they are released,” Kupers writes to me in an email, “for example in their bedroom if they returned to the community, or in their cell if they went from SHU to general population in prison.” While Kupers says those with SHU Post-Release Syndrome can be successfully treated, they might continue to feel symptoms like social anxiety and depression. “The scars will remain,” he says.

The Step Down process begins when the inmate appears before the Departmental Review Board, a panel of CDCR administrators that reviews the inmate’s files and assesses placement in one of five steps. The warden of Pelican Bay, Clark E. Ducart, explains that this process is time-consuming because the board reviews an inmate’s entire file, which might be many binders long. “Some of them have volumes of documents,” he says, in a tone that implies those documents contained ugly reports of prisoner behavior.

The CDCR, for its part, has been trying to ensure that all eligible inmates appear before the board swiftly. Prior to the October settlement agreement, according to CDCR Deputy Press Secretary Terry Thornton, 2,174 inmates who were serving indeterminate terms have been reviewed; 1,671 of them have been released directly to general population housing, and 325 have been placed in the Step Down Program. (The current Pelican Bay SHU population is 772, and there are fewer than 2,300 inmates in SHUs throughout the CDCR.) This means that 75 percent of the men once deemed to be too dangerous for the general prison population are now living a comparatively “free” life.

OPINION: LOOKING FOR A SUPREME COURT JUSTICE TO TACKLE PROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT

Writing for SCOTUSblog in February, President Barack Obama shared some of the qualities he’s searching for in a Supreme Court nominee to replace the late Antonin Scalia. President Obama said he will choose someone committed to “impartial justice” and who “grasps the way [the law] affects the daily reality of people’s lives in a big, complicated democracy, and in rapidly changing times.”

In an op-ed for the Huffington Post, attorney Bidish Sarma calls on Obama to nominate someone who will hold prosecutors accountable, and weed out misconduct, noting that the US Supreme Court has unique powers to end the era of the “invincible prosecutor.”

In the past, we at WLA have pointed out a number of stories of prosecutorial misconduct involving breaches such as withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense, coercing witnesses, and perjury. Orange County is grappling with jailhouse informant-related misconduct scandals that has plagued the county District Attorney’s Office. The alleged misconduct resulted in the removal of the entire DA’s office from the high-profile case of mass shooter Scott Dekraai and the unraveling of a number of other cases.

Link to Orange County DA stuff

And it’s rare that courts, juries, and bar associations will hold errant prosecutors accountable.

Sarma says it’s time for the US Supreme Court to take action. Here’s a clip:

There are five primary means to keep prosecutors from overstepping the bounds of propriety and fairness: (1) criminal courts can overturn convictions obtained as a result of prosecutorial misconduct and dismiss unwarranted charges; (2) juries in civil courts can hold district attorney offices liable for prosecutorial misconduct; (3) professional associations and disciplinary counsel can fine, suspend, or disbar prosecutors who violate ethical canons; (4) district attorney offices can meaningfully train their assistants and punish those who engage in misconduct; and (5) the Department of Justice can initiate proceedings against prosecutors who violate federal civil rights legislation.

Option 1 is not promising. Courts are reluctant to reverse convictions, especially in jurisdictions where the judges themselves are elected officials. The Thompson majority demolished option 2. And, as anyone who with experience in the criminal justice system can tell you, options 3, 4, and 5 are almost never utilized. Disciplinary actions against prosecutors are extremely rare, if not non-existent in most jurisdictions. Though some offices provide sufficient training, the conduct that put John Thompson behind bars is all too common when district attorneys are under intense pressure to secure convictions to succeed in competitive elections. Finally, the Department of Justice has hardly ever enforced certain laws that impose fines on prosecutors for their civil rights violations.

But, the Supreme Court has the power and influence to bring all five of these options to life. If it begins to infuse meaning into the due process and equal protection doctrines meant to protect criminal defendants from prosecutorial misconduct and overreaching, lower courts will follow its lead (and option 1 will become viable again). If the Court revisits its tight-fisted jurisprudence on prosecutorial civil liability, juries can speak into the system and hold offices accountable again. And, if the Supreme Court puts meaningful prosecutorial accountability on its agenda, bar associations and district attorneys and perhaps even the DOJ might acknowledge incentives to play a broader role in regulating how the most powerful players in the criminal justice system administer that power.

The Supreme Court has for too long advanced and entrenched an ideal of the “invincible prosecutor.” The nomination of a new justice provides the president with an opportunity to do more than look for someone with stellar credentials. If he truly values someone’s experiences and ability to see how the Court’s opinions affect people’s daily lives, President Obama should nominate someone who will, among other things, take prosecutorial accountability seriously.