There is a very worthwhile two-part series by Kurt Streeter that is running in the LA Times Sunday and today. It is about a 70-year-old federal Judge who went out on a legal limb to snatch a 3-strikes case.

The judge in the story is Spencer Letts, a Republican whom Reagan appointed to the bench, born to a privileged family, attended Yale then Harvard Law, went to a high profile law firm before becoming the legal eagle for Teledyne where he made enough money that his family would be permanently comfortable.

But, Letts didn’t fit into whatever neat little boxes his background might suggest. He was his own man. And as a jurist he was reluctant to put others into neat little boxes, despite a system that seemed to conspire to do so.

Here is an excerpt about Judge Letts from Streeter’s story.

Unable to consider the context of cases, he grew indignant at being required to sentence wrongdoers to decade-long prison terms when he often felt they deserved far less. His anger intensified when he saw that almost every defendant coming into his courtroom was black, even as statistics showed that most drug users were white.

He was struck by how smart many of them seemed, how driven. Born into different circumstances — into his circumstances — some also might have become vice presidents at Teledyne, he figured.“I began to see that it is all too easy for a judge to just put a C for convicted on a guy’s forehead and then to walk away like the guy is, and always will be, nothing,” he said. “It hit me — I am going to try my best, from then on, to extend myself, see their humanity and let them see mine.”

He fought hard against mandatory sentences, calling them discriminatory and even unconstitutional, disparaging them in opinions that circulated in legal circles and earned him the ire of federal prosecutors.

The 3-Striker in the story is Michael Banyard. Here is some of what Streeter writes:

Michael Banyard was born in Compton in 1967, the son of a truck driver and a beautician. “When I gave birth to Michael he had a 102-degree fever,” said his mother, Obie. “I remember the doctors putting him in an ice bath and I remember how terribly worried I was for my child. That was the start.”His mother recalled that young Michael was sweet, shy and deeply affected by what happened around him. When he was 5, gang members broke into the family’s home, rampaging through everything. His mother never forgot the look on her son’s face when the break-in was discovered: fear, helplessness and anger. They were emotions he could never seem to shake.

His father left the family when Banyard was in grade school. The men he looked up to were gangsters. By 16, he was one of them, a full-fledged member of the Compton Santana Crips who sold crack on the streets. His gang name was Loco Mike.

That was one side of him. The other was the polite, razor-smart, church-going teen who would retreat to his room for hours, hounded by shame for his street life, remembering childhood days when he would fall asleep on his father’s chest.

At 17, he turned to the drug he had been selling. It wasn’t long before crack owned him. He sold his girlfriend’s jewelry to pay for a high. Then he hocked her Chrysler LeBaron to a stranger. He went to a police station and begged to be arrested because he couldn’t stop. The cops told him to go home.

In 1988, he was in a minor car wreck and stole $6 from the other driver. He was arrested and convicted. It was his first time in prison, his first felony. Under California law, his first strike.

When he got out three years later, he fared well for a while, managing his mother’s Inglewood beauty shop. But one night he got high. He fought with his girlfriend and she called the police. He pleaded no contest to assault and was placed on probation. It was his second strike.

By 1994, he had lost every vestige of control over crack. His addiction pushed him onto the forlorn patch of downtown streets that is skid row. He was arrested for a string of petty crimes, but mostly the cases were dismissed. When they weren’t, he got probation or a few weeks in jail. Then he was back on the streets.

He no longer called his family, even his mother. He smelled of urine, slept on sidewalks and underneath cars. There were times when his clothing was stolen, so he fashioned pants out of large plastic garbage bags, tied at his waist.

One day, he made his way to a freeway overpass and looked down at the cars. He was ready to jump. But at the last moment he thought of his mother and stumbled away.

On Sept. 4, 1996, a stranger approached with crack. Suddenly, cops swooped in. They would later testify that they saw drugs drop to the ground as they approached, drugs Banyard had just bought. It was less than a gram of crack, barely enough to fit under a fingernail. That didn’t matter. He was convicted and it was his third felony.

California’s three-strikes law mandated that he be sent to prison for at least 25 years. At the end of that time, his release would be subject to approval from a parole board. He could die behind bars.

:In prison, Banyard was free from drugs. His mind cleared and his anger softened. He gained a new sense of spirituality and spent almost all his time in the prison law library, preparing appeals. A state court reviewed his case and turned him down. A federal magistrate said his claims lacked merit. The attorney general said he should remain in prison.

By 2002, he was down to one last appeal –– to the U.S. District Court, where his case went to Letts. The judge was approaching 70 then, working less and reflecting on his life. He thought often of his father — a steady, stealthy drinker late in life — and of a cousin who became a fervent member of Alcoholics Anonymous. He had empathy for their struggle. He had his own dark bouts with depression and sometimes talked openly about them in court. He understood how it felt to battle despair.

It was against this backdrop that he took Banyard’s case.

Read the rest of Sunday’s story here.

And then go on to Part Two here.

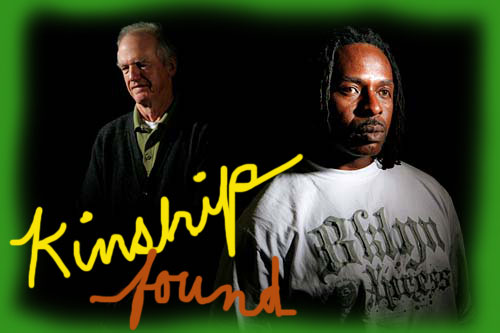

If you think this story has a nice, tidy, upbeat ending, it doesn’t. But it ends with hope….a strong dose of humanness, and a sense of kinship found.

Photo by Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times

Does the judge want to know why so many black males are in the criminal justice system?

You could have stopped there. That’s Banyard’s problem and the major contributor to black crime, and it’s rampant in the black community. Why are black males being so irresponsible to their kids and families?

A very interesting story.

I just read another great human story about a journalist who was the victim of some random street violence. In case any of you are interested:

http://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/September-2009/A-Mugging-on-Lake-Street/index.php?cparticle=1&siarticle=0#artanc

Actually, Woody the answer is much more complicated than that. Apparently you missed the point that more blacks appeared in his court than whites although the rates of substance abuse are statistically higher in the white communities than in the black communities.

I can tell you story after story about police officers, during Banyard’s childhood, systemically would take white youth to the police station then call their parents to pick their child up after the commission of a minor offense. Black youths were taken to the police station, arrested, then released. What’s the difference you might ask? The difference is significant, in that, the white youth did not have a criminal record and the black youth would have a string of offenses listed on their rap sheets stating, “counseled and release.”

Institutional racism existed then and still exists today. Yes, an absentee father is not an optimum situation but let’s not confuse the premise of the article noted above.

I just wanted to say thank you very much for publishing the story. To date me and Judge Letts are the best of friends and we work togeter at encouraging others who may have a problem at tearing down the negative walls of self-defeat. I volunteer at the Los Angeles Dream Centers Discipleship Program.

Michael, that’s fantastic to hear. People like you matter so very much and are such a great inspiration to others.

I welcome those who support change to follow me, Michael Banyard on twitter@banyardvsduncan. Thank you for all your support. Peace