The nation’s long addiction to locking people up for lengthy periods of time as the solution to a set complex social problems, led to a mass incarceration crisis that still unnecessarily damages the futures of individuals, families, and communities.

In the last decade or so, however, a growing public outrage at the profound racial inequality and general class-based unfairness that has become embedded in criminal justice system — both nationally and locally — has led counties and other municipalities around the U.S. to adopt a wide range of diversion programs, designed to create other ways to address an array of problems, rather than the catch-all of prison, with its devastating collateral effects.

Naturally, all of these programs are not created equal, thus the effect of these programs on justice-involved people can vary greatly.

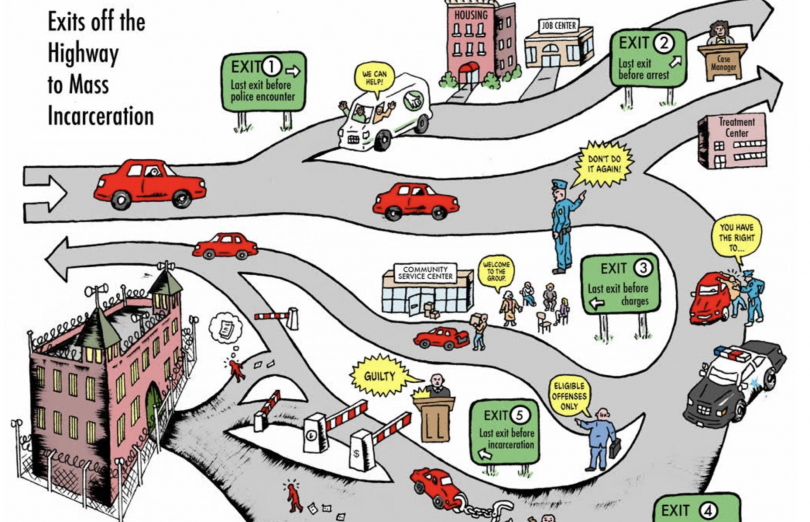

To help the rest of us sort through the various approaches, the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative has put out a well-written new report, released Tuesday, titled Building exits off the highway to mass incarceration: Diversion programs explained.

Through this new report, authors Leah Wang and Katie Rose Quandt, have created a smart primer on the topic, which breaks down the various kinds of diversion programs into five kinds of “exits,” including regional examples of the various strategies, which are already up and running.

The result is a helpful introductory text into how in each category works, including what the approach does best, and it does what less well, when human and statistical outcomes are scrutinized.

Here’s a quick look at what Wang and Quandt have to tell us. But, please check out the complete report, as it’s very much worth your time.

Pre-police diversion

The authors introduce the first diversion strategy, which they label Exit 1, with quote from the Civil Rights Corps.

“You shouldn’t need to be arrested, let alone prosecuted and jailed, to receive social services.”

But, of course, so often has arrest has becomes the sole route for a great many people who are struggling with issues of mental health, substance disorders, a lack of housing, poverty, unemployment, or some combination thereof.

Yet, while, police and jails are supposed to promote public safety, as PPI has written in the past, too often, “law enforcement is called upon to respond punitively to medical and economic problems unrelated to public safety issues.”

As a consequence, the majority of people arrested repeatedly, are — if one drills down — primarily battling economic and health disadvantages that put them in more frequent contact with police.

With this and other problems in mind, pre-police diversion refers to support and treatment within the community, or a non-law enforcement agency that address underlying problems that increase the likelihood of police encounter.

For each of these, the authors suggest programs that “identify individual needs, use evidence-based practices, and do not involve police,” thus removing this first “on-ramp” of arrest from being a catch all tool, rather than one used when truly needed.

Among their examples of pre-police diversion PPI points to Eugene, Oregon’s well known CAHOOTS program. (CAHOOTs, for those unfamiliar, stands for Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets).

Founded in 1989, the program causes calls to 911 or the police line to be diverted to CAHOOTS if they involve “mental health-related crises, including conflict resolution, wellness checks, substance abuse, suicide threats, and more.”

CAHOOTS, which has now been replicated elsewhere in the nation, then sends teams of two unarmed responders — namely a medic and a case worker. Although CAHOOTS is funded though the local police department, it operates independently.

As WitnessLA wrote earlier this year, out of the 24,000 calls that CAHOOTS answered in 2019, teams only called for police backup 150 times, and is estimated to save the city approximately $8.5 million per year.

Meanwhile, back in Los Angeles, the LA County Board of Supervisors voted earlier this year to co-sponsor

AB 988, a CA bill to adopt “988” as an alternative to calling “911” for mental health emergency services.

Existing California law requires all local police agencies to use “911” as their primary emergency line, but in 2020, federal lawmakers enacted the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act, which will set “988” as the national suicide prevention and mental health crisis hotline.

States are required to implement this system by July 16, 2022. Under California’s AB 988, the state would formally adopt the federally required program immediately — as an urgency statute.

Police-led interventions, pre-arrest

The number two exit from the road to incarceration, according to the PPI report, is the strategy of pre-arrest interventions, which are led by law enforcement.

Due to the fact that these diversion initiatives happen at the “pre-arrest” stage, this strategy, like pre-police diversions, allow people to avoid the many unnecessary consequences that accompany being arrested and booked.

These pre-arrest programs instruct or empower police officers not to arrest in certain situations, such as when someone with a substance use disorder violates a drug law. Instead, officers are allowed to impose a lighter sanction such as a warning or refer the person that they would otherwise have arrested to a service provider. These diversions avoid unnecessary arrests for low-level offenses such as drug charges, public order offenses, drunkenness and similar.

LEAD, or Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (a title that is the process of being renamed as Let Everyone Advance with Dignity), is a national pre-arrest program, that originated in Seattle.

LEAD allows police to refer someone who would otherwise be arrested for low-level drug offenses, criminalized sex work, or other “crimes of poverty,” or who is struggling with behavioral health problems.

The case manager responds to the individual’s immediate crisis (such as connecting participants with drug and behavioral health treatment), while also connecting them with long-term intensive services (such as housing and healthcare), stressing that many participants are not poised to enter treatment until other needs have been addressed.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) is a big fan of LEAD, which it rates as a “promising” evidence-based program for preventing future rearrests. Following Seattle’s lead, other cities that have instituted LEAD include Santa Fe, NM, Albany, NY, Fayetteville, NC, Portland, OR, Huntington, WV, Charleston, WV and Baltimore, MD — and more.

San Francisco and Los Angeles County have also instituted pilots of LEAD. According to a 2020 evaluation, while promising, both the SF and the LAC LEAD programs have various challenges to overcome.

Prosecutor-led interventions

With their third “off-ramp” category, authors Wang and Quandt point to prosecutor-led programs, in which the prosecutor may initiate pre-charge diversion initiatives, thus enabling them to postpone filing charges, and instead require the individual to complete a program or fulfill a set of requirements. However, failure to fulfill the program or list of requirements, means prosecutors may resume the normal court process, “turning the individual into a defendant.”

These programs are generally optional for participants, although participation fees and program capacity may block access for some people who wish to opt in.

In their writing about prosecutor-led intervention, the PPI points to WLA’s friends at the nonprofit Fair and Just Prosecution, which, in general, acts as a resource for prosecutors and, in the case of prosecutor-led diversion, offers smart guiding principles for implementing diversion programs, including tracking outcomes and relying on clinical staff to develop evidence-based treatment plans.

FJP also advises prosecutors interested in diversion to look beyond their role, and partner with institutions and community based providers outside the criminal justice system.

Judge-led interventions

Even after a prosecutor chooses to bring charges, there may still be one more opportunity for diversion when a case gets to court, the PPI report authors explain.

“Problem-solving courts are intended to divert people with substance use or mental health disorders, and sometimes other circumstances, linking them to treatment and requiring them to meet certain conditions after they’ve entered a plea,” according to PPI.

Many states also give judges discretion to offer what is known as deferred adjudication to defendants, say the authors, which is less focused on a specific underlying problem but allows someone to complete a “sentence” in the community to avoid a permanent conviction record and/or being sentenced to a term of incarceration.

Alternatives to incarceration

Off-ramp five according to the report consists of official “alternatives to incarceration,” which the reports authors don’t really see as a true offramp at all, since these are not diversion programs, and are not true “alternatives to incarceration,” even though they may allow people to avoid being jailed or imprisoned, or at least shorten the time behind bars.

These alternatives include probation, house arrest/electronic monitoring, mandated community service, fines and restitution, and some restorative justice programs. In other words, the individual is still under the oversight of the justice system, even if they’re not locked up.

In the end, as the report points out, the most successful diversion strategies are those that shift people out of the criminal justice system as early as possible, and hopefully altogether, thus hopefully avoiding the long-lasting consequences of a criminal record.

Plus, well-designed programs that are based on public health research and harm reduction principles, have a better chance of success for those people whom the programs serve.

All that being said, the authors acknowledge that no single diversion program will address every need, or prevent every unneeded police encounter.

“The landscape of diversion is vast,” they write, “and the design and implementation of each program matters.”

The PPI also cautions that diversion programs “are inexorably local in nature, and are as unique as they are similar.” In the end, they write, “communities will have to decide what diversion points (or “exits”) are appropriate and feasible now and in the future.”

The graphic above is from the PPI report Building exits off the highway to mass incarceration: Diversion programs explained, and was created by talented artist and illustrator Kevin Pyle.

[…] The Art Of Building Exits: How Diversion Programs Address The Devastating Effects Of Mass Incarcerat… Celeste Fremon, WitnessLA […]