On Tuesday, June 14, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors was scheduled to consider a motion authored by Supervisor Holly Mitchell to find funding to expand the Office of Diversion and Reentry, at the continued urging of community groups focused on reducing the number of people in the county’s jails. Supervisors Janice Hahn and Sheila Kuehl, however, penned an amendment that made significant cuts to the motion.

Seeing that the board was divided on the issue, and reportedly feeling concerned about the nature of the amendment, Mitchell chose to put the motion on hold until the board’s June 28 meeting.

Since 2015, LA County’s Office of Diversion and Reentry has operated a series of critical programs that have brought thousands of vulnerable people out of LA’s jails and into services and permanent housing.

However, ODR has not received enough funding to expand its diversion services. On top of that, in April 2021, ODR’s housing programs, which provide permanent supportive housing for as long as participants need it, hit a 2,200-person population cap imposed by the LA County CEO.

These bureaucratic barriers have left people behind who would otherwise get help and housing meant to break the cycle of incarceration. Those left out include chronically homeless individuals, those with severe mental illness, and jailed pregnant people. (To learn about ODR’s work diverting pregnant people from jail, read our five-part series, Pregnant Behind Bars.)

Over the last couple of years, the supervisors have taken small steps to build up funding for ODR, but the office has yet to reach a level of funding that would fully sustain its operations on an ongoing basis. And sustaining ODR’s programs in their current states, does not allow room for expansion of the housing-focused programs.

Yet, community advocates and local leaders agree expansion will be critically important to the effort to close the dangerously deteriorated Men’s Central Jail and to realize the county’s plans to create a “care first, jail last” justice system.

The county-orderedMen’s Central Jail Closure Report prescribed a gradual 3,600-bed increase to ODR’s housing capacity, specifically for people with high mental health needs, in order to close the jail expeditiously.

“With the appropriate investments, these programs are ready to be scaled up immediately to serve individuals who could be diverted out of jail custody and have serious mental health, SUD and/or medical needs,” the report stated.

During a budget-focused meeting on April 26, Supervisor Holly Mitchell expressed the urgent need for expanded diversion. “It is essential that we invest in community-based systems of care, and create 3,600 new ODR mental health beds, so that those who are suffering from mental illness do not continue to deteriorate in jail,” Mitchell said. “I will reiterate: we must expand funding for the Office of Diversion and Reentry. That’s critical.”

A little over a month later, a motion pushing toward that goal appeared on the board’s agenda.

If it had passed, Mitchell’s motion would have directed the county’s CEO to report back with recommendations about how to increase funding in the 2022-2023 budget to expand ODR housing by at least 500 beds by July 1, 2023. It would have also set the CEO to work with ODR and other stakeholders during the following year’s budget process to come up with funding recommendations for further expanding ODR by an additional 1,000 beds in fiscal year 2023-2024, and, to continue that growth until ODR reached an additional 3,600 beds (5,800 beds in total) for its housing programs.

During the board meeting on June 14, several members of the public called in their support for the motion. Dozens more voiced their support by submitting written comments before the meeting.

One caller, a woman named Robin Williams, said her time receiving ODR’s housing and services “completely helped change my life.”

Once released from jail into ODR housing, Williams said she was able to get critical mental health services. “And now I am a productive member of society,” she said. “I have worked in a full-paid position, and I no longer have the trauma that I was living with for many, many years.”

Williams now works as a care coordinator for homeless services, giving back to her community, she said.

Without the program, Williams said, “I would not be the woman that I am today.”

In a write-in comment, Michael Saltzman, an LA County Deputy Public Defender, called ODR “the best program in the County” for diverting people with mental illness from the jails into effective treatment. “If the County is serious about the ‘Care First, Jails Last’ model, expanding ODR’s capacity is absolutely necessary,” Saltzman wrote.

After the public comment period was over, however, listeners learned that the supervisors would not be voting on the motion that day.

Supervisor Mitchell’s senior justice deputy described the problematic nature of the amendment during a virtual town hall meeting.

Amendment Trouble

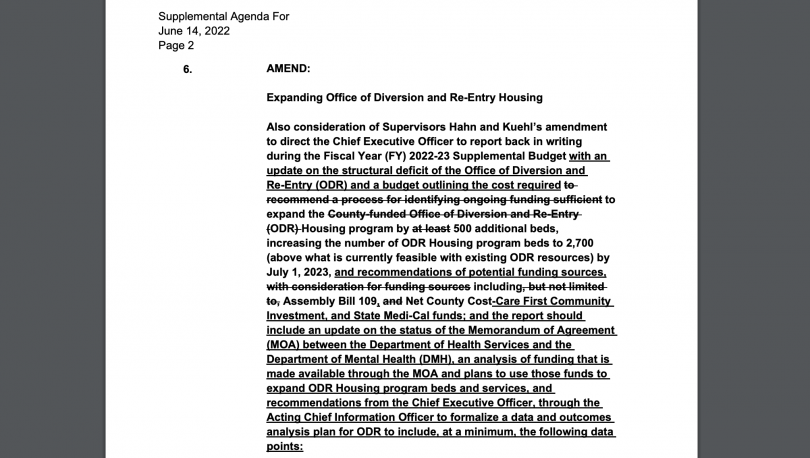

Four days earlier, on June 10, the board’s supplemental agenda for the upcoming meeting was released to the public. Within that updated agenda was Supervisors Janice Hahn and Sheila Kuehl’s amendment to the ODR motion, much of which seemed to defeat the purpose of the original motion altogether.

While the amendment retained language calling for an exploration of funding possibilities for adding 500 beds to ODR’s housing services, the supervisors eliminated the directive to the CEO to seek funding to expand capacity beyond that 500.

The amendment also called for a long list of potential datasets to be collected and analyzed, including the number of clients referred (and those not accepted) into ODRs programs, the number of clients who transition into non-ODR long-term housing, the number of clients who “elope” from the programs, the number of participants “who fail due to non-compliance or are engaged in violence, substance use, or other behaviors for which they must be moved to higher levels of care,” the number of people who refuse the diversion services, and participants’ recidivism rates.

Supervisor Mitchell’s senior justice deputy, John Matthews, described the problematic nature of the amendment during a virtual town hall meeting Tuesday evening, following the board meeting.

Hahn and Kuehl’s amendment, he said, changed “the nature” of the original motion, and put a focus on obtaining more data about ODR.

Yet, we already have a lot of data showing that ODR works, Matthews said.

Among that data is a 2019 RAND report, which showed that 74 percent of people in ODR’s supportive housing programs maintained housing stability over a 12-month period. Additionally, 86 percent of participants remained free of new felony convictions a year after they entered ODR housing.

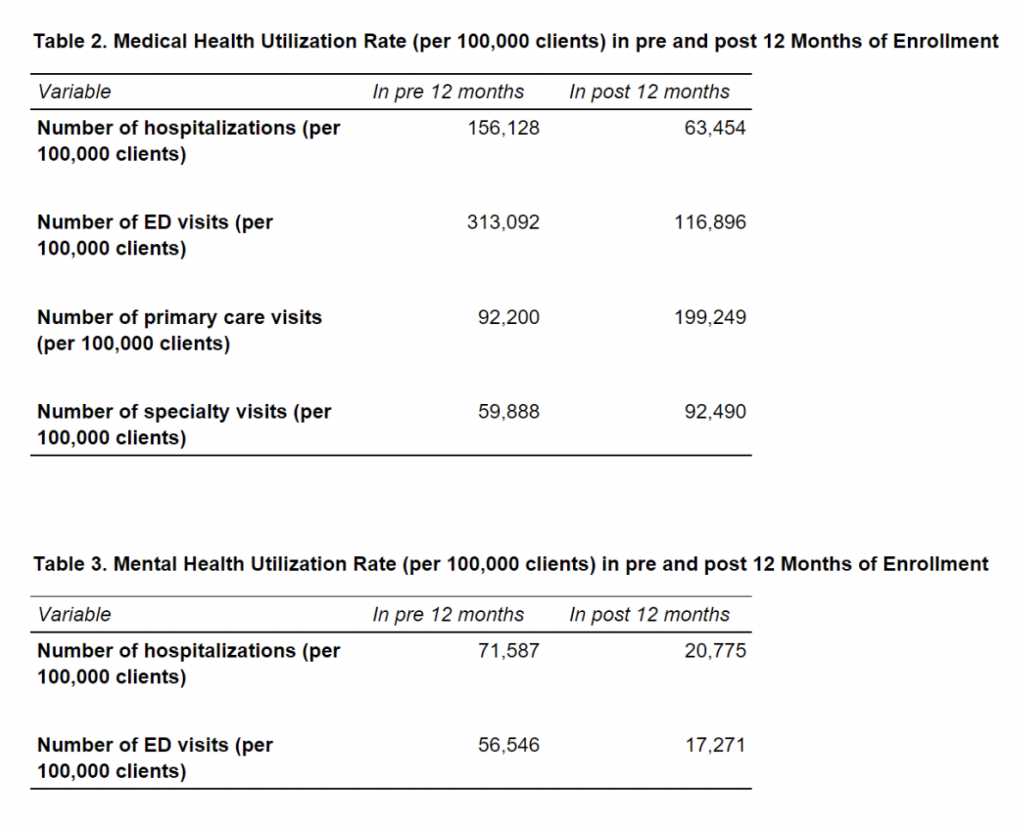

In addition, Mitchell’s motion revealed that a yet unreleased UCLA study of nearly 1,000 ODR clients found that the participants’ hospitalization and emergency room visits for medical and mental health reasons dropped dramatically between the year before they entered an ODR program, and the year after.

Concerns over the ways that the amended motion might actually negatively impact ODR led Supervisor Mitchell to table the issue until June 28.

“The jails are maintaining 2021’s rate of one person dead per week into 2022.”

Meanwhile, the LA jail system is “in crisis,” according to a June 10 letter to the board from the ACLU of Southern California, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) of Greater Los Angeles, Disability Rights Legal Center, Mental Health Advocacy Services, and Frontline Wellness Network.

A carceral system in crisis

Jail deaths — specifically homicides, suicides, and deaths labeled as resulting from “natural” causes — in LA County are at record highs, the advocacy groups pointed out in their letter.

“The jails are maintaining 2021’s rate of one person dead per week into 2022,” they wrote.

“To refuse funding for ODR is tantamount to a deliberate indifference to the suffering of people with mental illness in the jails and an indifference to the unconstitutional conditions in which they are kept.”

Moreover, of the 13,000 people in LA County’s jails, nearly 43 percent need mental health treatment, Mitchell said in her motion. That rate jumps to six out of ten among the women who are locked up in LA.

“If someone is arrested and booked into the LA County jails today, and that person requires Medium or High Observation Housing (MOH or HOH) due to a mental health need, the Sheriff’s Department does not have a place to house that person,” the advocacy groups wrote. “This is not hyperbole. There is currently no place for that person to go.”

As a consequence, “dozens” of people have been held far beyond the 24-hour limit in the Inmate Reception Center, leaving people sleeping on dirty, trash-strewn floors. “Mentally ill individuals have been shackled for days in the Inmate Reception Center,” Pamila Lew, an attorney at Disability Rights California, told the board during the Tuesday meeting’s public comment period.

“To refuse funding for ODR is tantamount to a deliberate indifference to the suffering of people with mental illness in the jails and an indifference to the unconstitutional conditions in which they are kept,” the group concluded in their letter. “The County and this Board cannot wait for another motion or another committee or another department. The people in our jails need ODR expansion now.”

So, what’s up with the pushback on the motion to boost ODR’s capacity and funding?

“We’re dealing with some political challenges, I think,” Mitchell’s justice deputy, John Matthews, said during Tuesday’s town hall. “We do have the benefit of having a board that I think wants to do the right thing.”

Yet, “when it comes to ‘care-first’,” Matthews said he hasn’t seen “a commitment to broad structural changes to the budget.”

Plus, each of the supervisors has initiatives they are focused on funding, even within the realm of justice reform, said Matthews. “So, they’re all thinking … how is the money going to this program going to impact the things that I want to fund?”

The justice deputy also highlighted the importance of community members and advocates speaking out on behalf of ODR and other initiatives that the community wants to see funded.

Matthews said he thought the reason the supervisors did not go ahead and vote on the amendment was due to the fact that the “community showed up” to share their thoughts and personal experiences with the board.

Attorney Pamila Lew, writing on behalf of Disability Rights California, said that “every day that the County fails to fund this effective program creates unnecessary harm to the hundreds of individuals, disproportionately Black and Latinx, who wait in jail when they could instead be served in the community by ODR.”

Her organization, Lew said, “respectfully opposes any proposed amendments” to Mitchell’s motion “that would delay expansion of the program or limit the number of individuals who could be more immediately served.”

In a write-in comment, Michael Hames-Garcia, a professor and former police commissioner for Eugene, Oregon, now living in Pico Rivera, called for a “robust expansion” of ODR and community-based services.

“For the past 29 years, I have studied and observed the effects of our criminal justice system on the most vulnerable members of our society, Hames-Garcia wrote. “The Board should pass the motion as it was originally written and reject any amendments that shortchange this critical county department.”

For now, ODR’s supporters will have to wait and see what the June 28 Board of Supervisors meeting brings.

What more data, Keuhl and Hahn? What do you need while people are suffering. Do the right thing and stop obfuscating. You’ll never know the damage you are doing until you have a loved one with mental illness.

[…] The county had an opportunity to hit that number last summer, when Supervisor Holly Mitchell filed a motion to find funding to expand the ODR’s capacity by 3,600 beds.The ODR takes people experiencing […]