As most readers know, in early January, 2021, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors announced that, after a nationwide search, the board had hired a new chief to run the nation’s largest, and arguably most complicated probation department.

Adolfo Gonzales, the new chief, was previously the head of San Diego’s probation department, where he was known as a strong reformer, particularly when it came to the youth side of probation.

Probation staff members in Los Angeles who have met Chief Gonzalez tell WitnessLA that they are optimistic about the department’s new leader. Yet, in the past two weeks, those same probation sources expressed concern that many of the new chief’s biggest challenges will be dealing with problems that are still being created by some of the members of probation’s upper management.

The following are a few of the examples these staff members and other probation sources cited.

A tragic classroom brawl

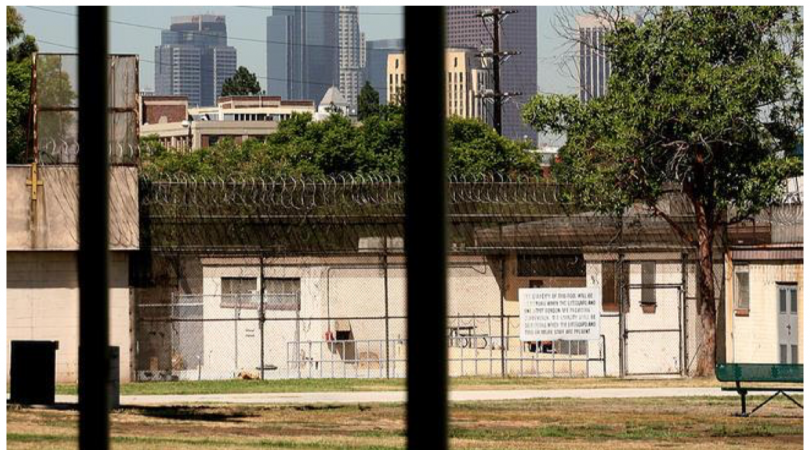

On Friday, April 30, violence broke out between teenagers at Los Angeles County’s Central Juvenile Hall during school time, when the kids were in the one of the facility’s classrooms.

The fight was not unexpected. The day before, Thursday, April 29, according to sources who work at Central, as it is called, there had already been a fight among some of the same kids in one of the classrooms.

On Thursday evening, and Friday morning, kids in the housing unit known as G-H were noticeably jittery because of the violence in the classroom, which “wasn’t over with.”

Hearing the reluctance of the youth to go to school, detention service officers who worked in the unit reportedly felt that cancelling class on Friday would be the safe and prudent choice.

“They would still have school time,” said a Detention Service officer (DSO) who spoke to WitnessLA about the situation. “But they could worked on school packets.” The school packets admittedly weren’t ideal, the DSO admitted, but not going to class on Friday would provide a day-long cooling off period for the previous days combatants and their friends. Then there would also be the weekend for things to further calm down.

“When the kids tell you they don’t want to go out, that means something’s up,” another probation source told WLA.

Yet, one of youth probation’s higher ups, Director Ildefonso Cárdenas, reportedly ordered the staff to take the G-H kids to class anyway.

“He knew the people from the DOJ were coming,” said a staff member. “And I guess he didn’t think it would look good for the minors not to be in class.”

The DOJ & Optics

By the DOJ, the source was referring to the California Department of Justice, and a January 2021 settlement agreement between then state Attorney General Xavier Becerra, and Los Angeles County, specifically pertaining to LA County Probation’s youth justice system. The settlement came about after a 2018-2019 DOJ investigation produced a scathing legal complaint, which stated that LA County Probation, along with related county agencies, “provided insufficient services” to the youth in its care, “and endangered youth safety.”

Now, under the new settlement, the county is required to engage in a wide range of corrective actions, which are overseen by an independent monitor and some subject matter experts, and are aimed at “securing positive outcomes for justice-involved youth and ensuring systemic improvements,” especially those youth residing in the county’s two juvenile halls.

Logically, these positive outcomes would include keeping the kids in the halls safe.

Nevertheless, Cárdenas reportedly gave his order. The G-H kids went to class and, sure enough, there was trouble. First the the tension reportedly ramped up in the classroom and the staff readied themselves. Suddenly, two kids faced off against each other, and in a lightening move, one kid grabbed his laptop and slammed the other kid with the electronic device, managing to simultaneously trip him, landing him on the floor. Seconds later, multiple other kids began battling.

As staff were starting to calm many of the classroom kids, some of the original combatants, plus another group of kids, made it through the classroom door, to a nearby outside recreation area. Several DSOs raced quickly after into the sunlight.

One of the DSO’s who had sped after the kids who had succeeded in getting outside, was Michael Wall, a well-liked fourteen-year veteran of LA County Probation who, as he jogged the direction the running boys had taken, began to slow his gate visibly on the video, which captured most of the brawl and its aftermath. Then Wall slowed completely and began to fall backward, reportedly going into cardiac arrest. A staff member caught his colleague as he fell. Then fellow staff members administered CPR until DSO Wall was able to be rushed to the hospital.

Within a few hours, word filtered out that Wall had gone into emergency surgery, but had not survived.

Is Michael Wall’s death attributable to the fights which arguably could have been prevented? Well, maybe not. At least not directly. But to many we spoke with, the tragic incident points beyond itself to what staff describe as a dangerous atmosphere in LA County’s juvenile halls, where priorities are mixed, and optics are often more important than the safety and well being of the kids in the county’s care and the staff members overseeing them.

Shanks, videos, and cell phones.

Meanwhile, at Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar, CA, on Friday, April 30, the same day as the classroom brawls at Central Juvenile Hall, and the day of DSO Wall’s death, another fight reportedly occurred. AT Barry J, as it is known, one youth reportedly tried to “shank” another kid. When a staff member attempted to intervene, the DSO was himself reportedly stabbed in the hand.

Earlier in the same month, on April 17, 2021 an unusual video surfaced on Instagram, which appeared to be made using a cell phone. The video showed a couple of boys smoking what appear to be large, hand-rolled marijuana blunts while they flash gang signs, just outside an area of Barry J that is known as Unit Z or the Compound.

It was the second such video that has surfaced, in recent months. The earlier video also recorded at Barry J, was posted in mid-November of 2020.

These videos made and posted from inside one of the county’s youth lockdowns obviously bring up several questions. Where did the kids get the cell phones to take the videos and post them online? Where did they get the means to light whatever it is they are smoking? And where did they get the marijuana, if it is marijuana?

“They get [phones] from staff members,” said a probation source familiar with the situation.**

“Definitely staff members,” said another probation source. “A lot of these young, inexperienced staff are not getting the training they need, then, right out of the gate, they’re assigned to work in the Compound with probation’s most challenging kids. They need the right training, and they needed experienced mentors.”

Absent that, said sources, some of the inexperienced staff do favors for the kids, like letting them use their phones. “They’re scared of these kids and they think that it’s the way to get on their good side.”

But, according to line staff, upper management on the youth side does not appear to be solving these and other critical problems, meaning neither staff nor youth feel safe.

“And when traumatized kids don’t feel safe they act out,” said one veteran staff member.

Problems at youth camps

The issues of safety, are not exclusive to the two juvenile halls.

Campus Kilpatrick, located high in the Santa Monica Mountains above Point Dume and northwest of Malibu, is unique among the county’s youth facilities. When its $53 million campus opened in July 2017, it was designed as an innovative pilot for a therapeutic, research-guided, “trauma-informed” environment that would set a new national standard for how a county can heal the lawbreaking kids in its care.

Yet, while the staff working at Kilpatrick appear devoted to their work, and to the vision the camp represents, farther up the agency’s food chain, the goals for the model facility appear far less clear — which brings us to Monday, April 26.

On that day, three Kilpatrick kids reportedly jumped another Kilpatrick kid, and took turns beating him up before staff could arrive and successfully pull the three attackers off. After the assault, which was captured on surveillance cameras, the injured kid received medical attention. When he returned to Kilpatrick, his three attackers still remained, which staff members did not consider a wise idea, even though, they pointed out, one of the attackers mostly seemed to have gone along with the other two.

When Campus Kilpatrick’s director was made aware of the incident, and reviewed the surveillance videos, he immediately notified his chain of command, and requested that the three boys who attacked the other boy be transferred out of Kilpatrick and thus kept away from the victim.

Reportedly, the director forwarded the request up the line to the appropriate Bureau Chief and the Bureau Chief forwarded the request to Dalila Alcantara, the person who oversees both both juvenile halls and all the youth camps. For unknown reasons, Alcantara reportedly denied the request to move the kids who had been the attackers.

“Not only is the assault on the victim appalling,” said one veteran probation source familiar with the incident, “but keeping the three minors in Kilpatrick with the victim also remaining, is an awful decision. After an incident like that a kid is traumatized in all kinds of ways. But decisions like this now have become the norm.”

As it happens, the three kids were eventually moved out of Campus Kilpatrick, but reportedly not because upper management reconsidered, but because they are each going to court due to their part in the beat down, which means they have been automatically transferred to juvenile hall.

We reached out to probation for information and comment but received no reply.

WitnessLA spoke to multiple sources for this story. These sources include seven people who presently work for LA County Probation, or are recently retired, who spoke to us on condition of anonymity.

Editor’s note

This story is the first in a new series on LA County youth probation called #SafetyIssues. So….stay tuned.

Part 2, which will arrive later this month, will be essential reading.

** Correction, Friday May 7, 4:22 p.m. This quote from one of our sources originally read, “‘They get them from staff members,” said a probation source familiar with the situation.” The pronoun “them,” while correct, was unclear, hence the correction.