EARLY ASSESSMENT OF PROP 47 IN LA, AND WHERE COUNTY AGENCIES THINK THE $$ SHOULD GO

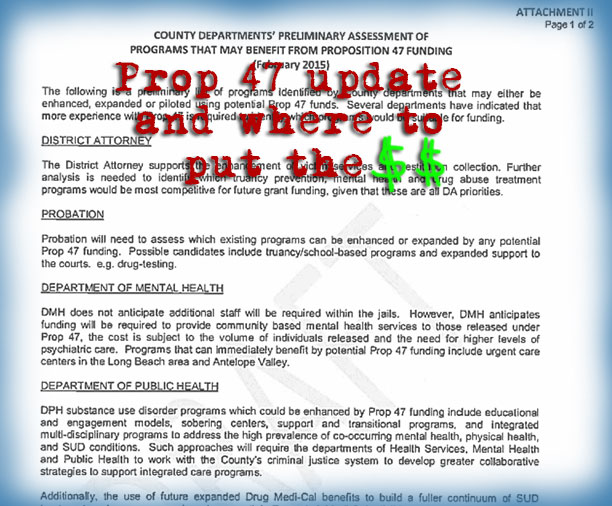

At a county public safety meeting on Wednesday, LA County interim CEO Sachi Hamai presented a draft report assessing the county’s implementation of Proposition 47. (Prop 47 reduced certain low-level felonies to misdemeanors.)

At the behest of the Board of Supervisors, the CEO’s office worked with other county agencies—District Attorney, Sheriff’s Dept., Courts, Public Defender, and Alternate Public Defender—to pinpoint the programs and efforts that could qualify for and benefit from Prop 47 funding, and to gauge the effects of the legislation, thus far.

Of the state money saved by Prop 47, 65% is to go to mental health and drug programs for criminal justice system-involved people, 25% will be spent on reducing truancy and helping at-risk students, and 10% will go to trauma recovery centers for crime victims. But it is still not clear how that money will get portioned out to counties, or if there will be restrictions on what the counties want to do with their money.

Some of the efforts county agencies flagged as deserving of grant dollars included victim services and restitution, community-based mental health programs for Prop-47ers, urgent care centers, the New Direction diversion pilot program to keep kids in school, and a reentry program for kids in probation camps.

The report says that it is still too early to tell what long-term effects Prop 47 will have in Los Angeles. However, county agencies shared some short-term effects, including courts clogged with people seeking downgrade their felonies, and a fewer number of offenders signing up for mental health and drug rehab programs.

The LA Times’ Abby Sewell and Cindy Chang have more on the report. Here’s a clip:

By the end of January, according to the Sheriff’s Department, the decrease in narcotics arrests was even greater, 48% from a year ago.

Local criminal courts will process between 4,000 and 14,000 applications from pre-trial defendants who were arrested for felonies but can now petition to have their charges changed to misdemeanors, the report said. Another 20,000 applications could come from people currently incarcerated, the report said.

Another category of cases is expected to keep judges, prosecutors and public defenders busy: the people who have already served their time and can now change the felony on their criminal records to a misdemeanor. Those cases could top 300,000 and date back decades.

The report quantifies an expected impact on court-ordered drug and mental health treatment programs: a decrease in enrollment because defendants are no longer threatened with jail time. Sign-ups for the programs decreased from 110 defendants a year ago to 53 in the first three months after Proposition 47 passed.

TECH IN JUVENILE LOCK-UP PART 2: SAN DIEGO INVESTS IN COMPUTERS, TECH EDUCATION FOR KIDS BEHIND BARS

On Tuesday, we shared the first of Adriene Hill’s two stories for NPR’s Marketplace about correctional facilities that have taken meaningful steps toward bringing education up to par for kids behind bars by incorporating educational technology into the curriculum.

Hill’s second story takes place in the San Diego Kearny Mesa Juvenile Detention Facility, where every kid has a laptop to use in class.

In San Diego County, the Office of Education has spent $900,000 on computers and accessories for kids in juvenile corrections facilities. Teachers are being trained on how to use the computers to help teach lessons, and tech instruction is now on the docket. And with the added technology, lessons can be tailored to kids’ individual needs.

Here are some clips from Hill’s second story:

Since July 2013, San Diego County Office of Education has spent nearly $900,000 on computers, printers and software for its secure juvenile facilities. Soon every one of the 200 kids here will have access to a Chromebook in class. All the teachers are being trained to run a digital classroom and add tech to the curriculum.

But getting to this point took more than a big investment. It took a significant culture shift.

“At first, we were a little nervous. I’m not going to lie,” says Mindy McCartney, supervising probation officer, who is charged with keeping the youth here under control.

“Everybody thinks they are going to use [the laptop] as a Frisbee, or attack somebody, or they are going to tag it and break it,” she says. “And it simply hasn’t happened.”

There was also anxiety about turning on the internet, even though there were firewalls and monitoring systems in place.

“We hear ‘internet’ and ‘access’ and we automatically get very paranoid and think the worst-case scenarios,” McCartney says.

But, so far, McCartney says there have not been significant problems. Kids aren’t using laptops as weapons. They’re not sneaking messages to gang members on the outside. In fact, teachers say the technology has made their students here more engaged in what they’re learning. That’s exactly the type of progress experts say the juvenile justice system desperately needs to make.

[SNIP]

In many ways, educational technology is perfectly suited to kids in custody. Students who have committed crimes are constantly being yanked in and out of class. They have court hearings and meetings with probation officers.

“We do have a population that moves around a lot,” says teacher Yolanda Collier. She says when students have their own computers and some lessons are online, they don’t have to fall behind.

Say there are some supplementary stories, an interview…videos…and such, if I want.

TEENAGERS HOUSED WITH ADULTS, PRISON RAPE, AND WHAT MUST HAPPEN BEFORE INMATES ARE SAFE

The Marshall Project’s Maurice Chammah has an excellent longread chronicling the failures of the justice system to protect inmates from rape, and the gaps in the Prison Rape Elimination Act.

Chammah focuses, in particular, on the sexual violence inflicted on vulnerable teenage boys who are placed in adult detention facilities.

Chammah tells the harrowing story of “John Doe 1,” a 17-year-old repeatedly brutalized by adult men in multiple prisons. John’s experiences are all-too-common, especially in states where 16 and 17-year-olds are automatically charged as adults. Here are some clips:

The second time David raped him, John says David held a homemade weapon to his throat. It was a toothbrush, wired up with four or five shaving razors.

The third and fourth times, David just left the weapon on his desk, in clear view, and relied on John’s fear to keep him passive.

Then, one morning around 6 a.m., while out on the yard for recreation, John says he saw David receive a mesh laundry bag from a prisoner he didn’t know. He could see that it contained meat sticks and bags of chips. These kinds of exchanges were common; he figured the other prisoner might be trading the food for the use of his cell as a quiet place for tattooing or some other illicit activity. (Official policy forbade prisoners from visiting other cells, but officers frequently looked the other way.)

That afternoon, John returned to his “house,” as prisoners call their cells, and saw his cellmate’s key—in this prison, every inmate had a key to his own cell—sitting on the desk. His cellmate was in bed. Feeling greasy after his kitchen shift, John started to undress so he could take a shower. As he took off his pants, he saw the mesh bag of food. He looked over and realized the man in the bed was not David. It was the prisoner who had handed over the bag of food. The man rose from the bed, grabbed David’s toothbrush weapon, held it to John’s cheek, and forced him down. This prisoner had a jar of Vaseline, but it did not do much; after he left, John found blood on his clothes.

John says he was raped several more times by both his cellmate and strangers. He was forced to perform oral sex, and he still remembers brushing his teeth twice to get the taste out of his mouth. He never told medical staff about his anal bleeding because he felt embarrassed, though because of a foot injury he was able to get painkillers.

John would later be asked why he did not tell correctional staff, since in theory they could have taken steps to protect him. “I didn’t know what to do,” he said. He assumed the staff knew what was happening. From their station at the end of the hall, the officers would see men going in and out of his cell and they would not intervene. The rapists would put a towel over the cell door’s window, which was not allowed but must have been noticed by officers making their rounds. John says some of the officers would even make jokes, calling him a “fag,” a “girl,” and a “bust-down.”

Two months after his arrival, John finally reached a breaking point. Around 2 p.m. one day, David tried to touch the middle of his back. John pushed his hands away. David forced him up against a locker and wrapped his hands around John’s neck. John wrestled his way out, and emerged from the cell barefoot. Hanging a left, he ran to the guard station, and begged them to assign him to a different cell. He didn’t mention the rapes, only his cellmate’s attempt to choke him. The officers allowed John to grab his few possessions and move down the hall, closer to their station.

His new cellmate was not a predator, but by then John had been tagged as easy prey. Two days after he was moved, another prisoner cornered him in his cell and raped him. It seemed like other prisoners had figured out his schedule—when he would be alone in his cell, or in the shower. He was called a “fuckboy,” a term for the men who are “gay for pay,” trading sex for food or other favors, even though John said he never did.

[SNIP]

It is impossible to know how many of the teenagers sent to adult prisons in recent years have been sexually assaulted, in part because so many of them have been afraid to report. (Rape outside of prison is known to be under-reported, and the same is true within prison walls, especially because prisoners face the possibility of retaliation by both correctional staff and other prisoners.)

Some corrections officials have pointed out that sexual assaults regularly occur in juvenile facilities as well as in adult ones. But many non-violent crimes lead to probation, rather than incarceration, when they’re handled by the juvenile system, and a 1989 study found that prisoners under 18 in adult prisons reported being “sexually attacked” five times more often than their peers in juvenile institutions.

CALIFORNIA TEACHERS WILL NOW BE TRAINED TO IDENTIFY CHILD ABUSE

Thanks to a new state law, California teachers and other school employees are now required to take an online training course on how to identify child abuse and neglect, and how to report it.

KPCC’s Adolfo Guzman-Lopez has more on the issue. Here are some clips:

“Nothing is more important than the safety of our students,” Torlakson said in a written statement. “The new online training lessons will help school employees carry out their responsibilities to protect children and take action if they suspect abuse or neglect.”

[SNIP]

[Stephanie] Papas, who helped create the new two-hour online training, said the course will help employees tell if a child has been hurt from abuse or from an accident, for example.

“We have photos that are examples of, say, a welt that is in the shape of a belt buckle or a slap on a child’s cheek that’s left a hand imprint,” she said.