On Tuesday, during the LA County Board of Supervisors meeting, Probation Chief Terri McDonald and Chief Deputy Probation Officer Sheila Mitchell, head of juvenile operations, shared their finalized plan for phasing out probation staff’s use of pepper spray in all of the county’s juvenile facilities by September 2020.

Oleoresin Capsicum, commonly called OC-spray, is commercial-grade pepper spray commonly rated to be 1,000 times “hotter” than a jalapeño pepper. Yet, a 2018 Office of Inspector General report found numerous instances of probation staff using OC-spray against kids who posed no threat to officers or other youth, who did not receive any warning that they might be sprayed, and who had medical conditions that, according to department policy, should have shielded them from being sprayed by staff.

The issue of pepper-spraying kids “is not a new problem,” Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas said Tuesday. “The county’s use–and some would argue, abuse–of pepper spray was well documented by the U.S. Department of Justice going back to 2003, already some 15-plus years ago.”

The probation department’s phase-out plan applies to Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall and Central Juvenile Hall. (One probation camp, Challenger Memorial Youth Center, and the county’s third juvenile hall, Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall, also still allow officers to solve problems by hitting kids with OC-spray, but those facilities will soon be closed.)

The plan comes as a result of a February 2019 motion calling for the eradication of OC-spray in juvenile lockups based on the Inspector General’s alarming 2018 report.

While the February motion asked that pepper spray be eliminated by the end of 2019, Chief McDonald says it will take until September 2020 to finish the job in the county’s juvenile halls, but that her department is committed to turning away from “a command and control” approach to juvenile justice.

“This is an important paradigm shift” for the department, moving from providing detention service to “a trauma-informed approach,” McDonald said. “I know this won’t be easy, but we must continue to profoundly change from an organization focused on control and confinement to one that is about engagement and rehabilitation.”

McDonald’s plan, the preliminary version of which we covered earlier this week, goes beyond just cutting pepper spray use and boosting de-escalation training. Additional reforms include increasing the number of correctional staff and clinical personnel in the halls and camps, and rolling out the rehabilitation-focused and trauma-informed LA Model to juvenile halls.

Probation and Department of Mental Health officials also intend to implement “resource teams” modeled after the sheriff’s department’s Mental Evaluation Teams, which pair officers with mental health clinicians to help de-escalate psychiatric crises. These hybrid probation/mental health teams will be available to help with de-escalation 24/7. The plan also includes the creation of “crisis stabilization units” staffed with medical personnel, which would do short-term psychiatric interventions, when needed, at each of the juvenile halls.

In their development of the phase-out strategy, probation officials met with Louisiana and Oklahoma officials responsible for the elimination of pepper spray in their own state’s lockups, as well as corrections officials in New York, San Diego County, and Santa Clara County.

The Four Phases

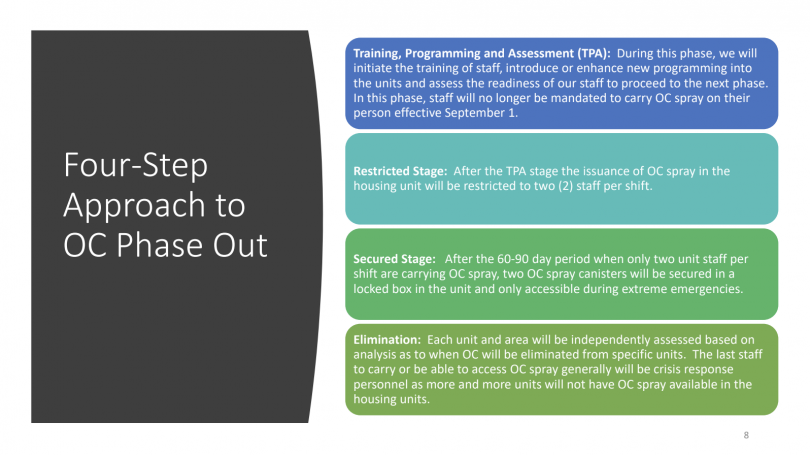

In brief, the department’s four-step strategy is the following:

• Phase 1 – Training, Programming, and Assessment (TPA). During this phase, the department will initiate the training of staff, introduce or enhance new programming into the units and assess to determine if staff are prepared to proceed to the next phase.

Staff will be provided with the option to still carry pepper spray during this phase as they receive the training necessary to feel comfortable to voluntarily relinquish it. This step may last 30-60 days.

• Phase 2 – Restricted Stage. After the TPA Stage (30-60 day period during which staff can opt to not carry OC spray), the issuance of OC spray in the housing unit will be restricted to two (2) staff per shift. (The manner of selecting the two staff members is under discussion with the unions. )This step may last 60-90 days, depending on outcomes.

• Phase 3 – Secured Stage. After the Restricted Stage (60-90 day period when only two unit staff per shift are carrying OC spray), two OC spray canisters will be secured in a locked box in the unit and only accessible during extreme emergencies.

• Phase 4 – Elimination. Each unit and area will be independently assessed based on analysis as to when OC will be eliminated from specific units. The last staff to carry or be able to access OC spray in a hall will generally be non-clinical crisis response personnel who are not assigned to living units. The analysis of readiness to eliminate the secured canisters of OC spray will be based on the status of program enhancements, staff and youth feedback on training and programmatic services supporting the effort, and other forms of analysis.

The Cost

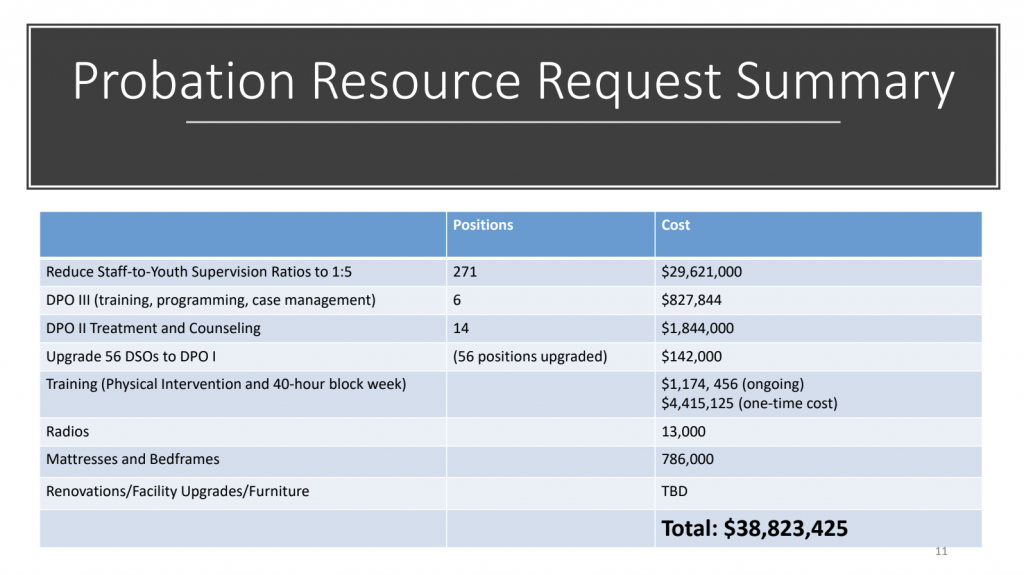

The phase-out, with its package of kid-supportive reforms, is expected to cost the department nearly $39 million. Probation will need the supes to come up with part of that money, but a portion is set to come from the probation department’s own reserves–savings from closing other juvenile facilities, according to McDonald.

“The truth of the matter is we’re not going to be able to provide the kind of services and support to do the kind of programming we need–the profound shift–with our existing staffing complement,” McDonald told the board on Tuesday.

Matters are complicated by the fact that, right now, there are chronic staff shortages at the county’s juvenile halls in particular, due to staff calling in sick, and other issues.

According to McDonald, reducing the staff-to-youth ratios from 1:8 to 1:5 will require 271 positions at a cost of $29,621,000. In addition, the plan includes the creation of 20 new deputy probation officer positions focused on training, treatment, counseling, programming, and case management, and the promotion of 56 officers to deputy probation officer positions. Meeting these additional staffing needs comes with a price tag of just under $2,814,000.

“We know that the county doesn’t have unlimited dollars,” Chief McDonald said. Then she pointed out that, since she took over as chief probation officer, with Chief Deputy Sheila Mitchell in charge of juvenile probation, the department has closed six juvenile camps, with a seventh on its way out. And “for the first time ever, we are closing a juvenile hall.” To bring “profound change” that results in rehabilitation, engagement, and “flourishing youth,” probation is “going to have to really profoundly change how we’re going to do business.” And profound change will require more money.

McDonald’s plan estimates that much-needed additional training for staff, including training on appropriate “physical intervention,” will run the county a one-time $4,415,125 and an ongoing $1,174,456.

Some of the costs McDonald listed were smaller than others. LA’s juvenile lockups also need new bedframes and mattresses ($786,000), radios ($13,000), and renovations (a TBD cost), according to the new report.

“Whether it’s the institutional design of the facilities, or just the bedding and mattresses” and group spaces in the halls, the facilities need an upgrade, McDonald told the board, “so that when a young person enters our facility, it doesn’t add additional trauma.” The halls should feel “more like a treatment space than a local jail,” she said.

None of the board members looked particularly thrilled, but no one appeared ready to say “no,” either.

“It is a large amount of money,” Supervisor Kathryn Barger said. “But at the same time, even the [staffing] ratio is something that, with or without the OC-spray debate,” requires careful consideration. “We need to look at this because the population that we currently have is far more complex than has been in years past. In part, its because we have not provided adequate resources to give them the services they need–and some would argue–the dignity that they deserve.”

The $39 million price tag was “a little bit of shock” said Supervisor Janice Hahn, when it was her turn. And that sum, she noted, does not include an additional $40 million for the Department of Mental Health’s part in the reforms. Yet, many of the reforms itemized in the plan, Supervisor Hahn conceded, should be implemented regardless of the pepper spray ban.

The county, Supervisor Sheila Kuehl said, has “been long on ideas” about how to fix juvenile probation, but “short on providing funding.”

The easy scapegoat

The county must continue to usher in reforms that reverse the harshly punitive culture that arose from the nation’s tough-on-crime movement, said Kuehl, who referenced the rise of the “superpredator” myth that came into being during the 80s and 90s, and pushed the idea that lawbreaking kids were inherently more dangerous than in previous generations.

“But it was really a difference in attitude” toward the kids, she said, not “a difference in the kids themselves.”

“We’ve seen some portion of probation officers here at the board telling us how threatened they feel, how dangerous the kids are,” Kuehl said. “Attitudes have to change, and eventually they do.”

According to Saul Sarabia, who chairs the LA County Probation Reform Implementation Team, “training and retraining,” alone will not bring about a full culture change that captures all of the people stuck in the old punitive mindset.” Probation “needs a specific strategy to … identify and deal with whatever it is that is allowing” that old culture “to continue to hold root in a very small population.”

That’s not to say that working with kids in juvenile halls is not often highly challenging work, Sarabia and others were quick to add. The probation department hopes to educate staff on “vicarious trauma”–or “compassionate fatigue”–that can arise when working for years in juvenile lockups—and to provide detention and probation officers with more tools and services to address their own needs.

The overarching attitude shift requires more than just the elimination of pepper spray, said Kuehl. “It’s training about de-escalation.” It’s “‘How do I do this without beating them up, how do I do this without twisting their arms?’ And we’re saying, there are ways. People have done it. And we want you to learn.”

Hoping to counteract a common theme that has often been put forth by some staff and others, Ricardo Garcia, LA County’s public defender, emphasized to the board that the kids the county’s camps and halls are not “the worst of the worst.” They are the same kids who have been in the facilities “all this time.”

The difference we see now, he said,” is that because of the work of our legislature, of this board, and even of the probation department,” the thousands of kids and teens accused of low-level offenses, who should not be “detained and caged, have been removed from these halls. And so we’re left with a smaller number—800.”

So while it may appear that these kids are “the worst,” said Garcia, “they are not.”

The kids currently in the county’s care are no different than the kids that have been there all this time, the public defender said. “They just, in my honest opinion, make an easy scapegoat.”

It’s easy to “point the finger at the person that is being traumatized,” Garcia continued. But that’s just an unwillingness to take responsibility “for the failure of ourselves” for not providing kids with the services they need and “desperately want.”

It’s crucial, he said, that the department doesn’t find itself in the same place in two years, “asking the same questions, articulating the same concerns, because, as you know, we’ve been down this road before.”

Garcia urged the probation department to take him up on his offer to provide kids with advocates from the public defender’s office who can work with youth and their parents and serve as their voice, and to “supplement the process.”

Supervisor Ridley-Thomas too said that change was way past overdue. The probation department’s “status quo simply is untenable … and blatantly indefensible,” he said.

Reforming the probation department will not be easy, Ridley-Thomas said. “It’s a heavy lift, but that’s why we use the language of transparency, of accountability,” and of “commitment that says: care first.”

[…] Probation Chief Terri McDonald Presents Plan to Phase-Out Pepper Spray in Juvenile Lockups (Witness LA) […]

LOL! Please remember these names Terri McDonald & Mark Ridley Thomas. These 2 have absolutely no idea. Remember them both because when this “plan” of theirs hits the fan & backfires & doesnt do anybody good but cost alot of tax people money. We’ll for sure know who to blame. This is absolutely criminal to your current employees & good luck trying to recruit new people to work here. Anyone with common sense will say No Thanks & go work elsewhere.

Terri McDonald is doing to Probation what she did to LASD Custody Division. She ran it right into the ground with her absolute incompetence and mismanagement. Is anyone surprised?