On Tuesday, May 2, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a motion to move the county closer to a goal of having 1,750 new beds to divert people experiencing mental illness out of LA County’s jail system and into supportive housing.

In October 2022, in a years-in-the-making decision, the supervisors voted to expand the Office of Diversion and Reentry’s housing programs by 750 beds.

ODR’s clinical diversion system cares for those deemed incompetent to stand trial, people with mental illness and drug use issues, pregnant people, and others better served by clinical care and community housing.

By the time the board agreed to add 750 beds, ODR’s much-lauded housing programs had already been operating at a maximum capacity of 2,200 beds for a year and a half, leaving people experiencing mental illness and others who could otherwise qualify for diversion waiting in jail.

While those 750 beds are in the process of coming online, the county is also figuring out how to make 1,000 additional beds available to ODR.

The issue is particularly urgent as the county is failing to comply with the terms of a 2015 federal consent decree over conditions and mental health services for people with mental illnesses in the jail system.

The county is also beholden to, and failing to comply with, the longstanding Rutherford v. Luna judgment, the result of a 1978 decision on a 1975 class action suit led by the ACLU, alleging unconstitutionally bad conditions within the jails. This lawsuit resulted in the ACLU being assigned to send monitors into the county’s jails.

Trouble at the IRC

Last year, conditions at the county’s jail intake center were so disturbing that the ACLU filed an emergency motion on September 8, 2022, asking U.S. District Judge Dean D. Pregerson, who oversees both the Rutherford agreement and the county’s federal consent decree, to issue a temporary restraining order against the county in the Rutherford case.

As WLA has previously reported, staff from both the ACLU and the LA County Office of Inspector General found that people were being chained to benches for days in the Inmate Reception Center (IRC). Some who were denied medications and medical and mental evaluations, died as a consequence.

Because of overcrowding, people not chained to chairs were often forced to sleep on floors covered with excrement and trash.

In his preliminary injunction, Judge Pregerson ordered the sheriff’s department to stop chaining people to chairs and other objects for more than four hours, to give medications out in a timely manner, and to keep the IRC sanitary, among other changes.

But the sheriff’s department found ways to subvert the judge’s rules, according to the ACLU. Thus, on February 27, 2023, five months after Pregerson issued the temporary restraining order, the ACLU filed a motion asking the judge to hold LA County, the Board of Supervisors and the new sheriff, Robert Luna, in contempt of court for failing to abide by the preliminary injunction.

The county has not fared much better with the consent decree, according to ACLU of Southern California Chief Counsel Peter Eliasberg and Senior Staff Attorney Melissa Camacho.

LA County’s non-compliance with the 2015 federal agreement “has been so flagrant,” Eliasberg and Camacho wrote in a letter to the Board of Supervisors on May 1, that the court recently set a series of smaller deadlines to lead the county gradually to full compliance.

The deadlines

The jail system categorizes people based on the level of mental health care they need. The two highest categories are P3 and P4.

P3-level people, according to the LA County Sheriff’s Department, are acutely mentally ill residents, who are not so ill that they require in-patient treatment, meaning they could be treated in community facilities. A person in the P4 category would be hospitalized for psychiatric care if they were not in jail.

P3 is a much larger group of people than P4, which only accounts for about 200 of the 7,000 or so people in LA’s jails with diagnosable mental illness, as of September 2022.

By the end of 2024, the county must reach full compliance on having adequate High Observation Housing (HOH) for people in the P3 category.

The county must also have enough inpatient beds for people assessed as P4 by the end of the third quarter of 2024. People in HOH must also have at least 20 hours of out-of-cell time per week by the end of the second quarter of 2025.

The county has said the county would have to create 1,500 new beds for individuals classified as P3 and P4 to successfully meet the deadline for full compliance on HOH housing in the jails.

As WLA has reported, the Office of Diversion and Reentry has had success in diverting jailed people in the P3 category, as well as those in lower tiers, into community-based housing and care.

Yet, even with this latest motion, the Board of Supervisors’ efforts to bring the jail system into compliance are projected to fall short.

The motion

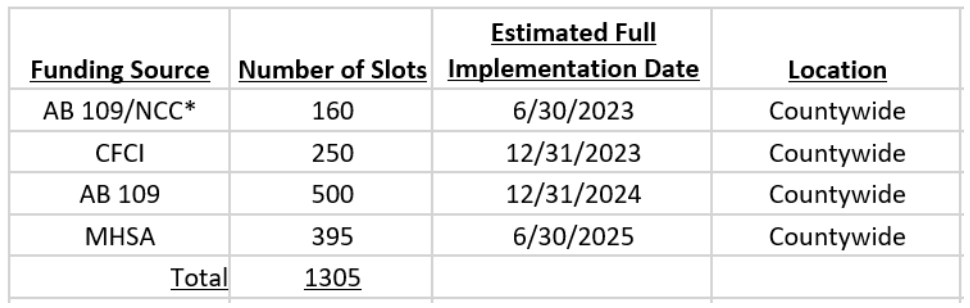

The motion, by Supervisors Holly Mitchell and Lindsey Horvath calls on the Interim Director of the Office of Diversion and Reentry to report back to the board in 90 days with an update on the 750 ODR housing beds that the board approved in October 2022.

Specifically, the board wants to know how many of the 750 beds are ready and available for use, how many are currently filled, and any difficulties ODR has experienced getting the beds online.

The supervisors also want an estimate for how long it would take ODR to increase the number of new beds by an additional 1,000.

The board has also asked what ODR needs to sustain and expand community-based programs, interim housing, permanent supportive housing, and staffing.

In the seven years between ODR’s 2015 inception and May 2023, county courts have taken 9,643 people out of jail and placed them in ODR’s programs. In those years, the department has produced impressive outcomes for those people who, for the most part, would have otherwise languished in jail.

Tuesday’s motion further directs the county’s CEO and ODR to report back to the board in 90 days with an update on efforts to establish formal data sharing and outcomes analysis for ODR’s programs.

Another 90 days later, the board wants the CEO and ODR to turn in a list of potential funding sources for fiscal year 2024-25 with which the county could begin establishing 1,000 more beds “over a multi-year timeline.”

That multi-year timeline is a serious problem, according to Eliasberg and Camacho.

Not enough beds to avoid contempt of court

Mitchell and Horvath’s motion, while necessary, the two attorneys said, is “not sufficient” to keep the county from being in contempt of court.

According to the timeline in the board’s latest motion, only 660 new mental health beds will open to divert people from the jails by June 30, 2024. Six months later, the motion estimates the number of new beds will increase to 910.

The county has a track record for dragging things out, including the necessary closure of the dangerously dilapidated Men’s Central Jail, and the community-based treatment and services that were meant to replace the jail. It took years for the board just to agree to expand ODR’s housing.

Even if the county meets the goal of 910 beds by the end of 2024, it’s far from the 1,500 beds needed in order to reduce the HOH population by 750.

Using the motion’s timeline for expanding ODR, the county would “in contempt of all the interim court-ordered compliance deadlines” for High Observation Housing between June 30, 2023, and December 31, 2024, according to Eliasberg and Camacho.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s legal team has said that the United States was willing to move for contempt if the county fails to meet those interim deadlines.

After passing the motion, “the county must do much more on an expedited basis to ensure the court does not impose substantial fines and other relief for violations of these court orders,” Camacho and Eliasberg wrote.