At the Los Angeles County Probation Commission Meeting held last Thursday, January 25, the main focus of discussion began with the general topic of how the Department of Mental Health was coordinating with the probation department to best help the youth in the county’s juvenile facilities—the camps and the juvenile halls.

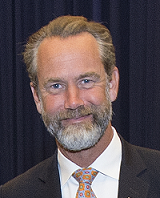

But, Dr. Jonathan Sherin, the man appointed to take over the county’s mental health agency (DMH) in late 2016, wanted to talk specifically about trauma and what his people and probation should be doing to address the trauma experienced by the county’s must vulnerable kids.

“I used to be a neurobiologist and I just want to say this,” Sherin told the commission members, plus the juvenile attorneys and others in the audience who’d made a point of showing up for this meeting. “The human brain is an extremely sensitive organ. Like other organs it is damaged by stress and trauma. If we can recognize that, and work at setting up systems to address that trauma, as opposed to seeing the results of repeated trauma in kids expressed as bad behavior, I think we’ll be doing our kids…a great justice.”

With all this mind, addressing trauma shouldn’t be just one focus when it comes to how the county addresses the kids in its care, according to Dr. Sherin. “It needs to be our main focus. But I don’t think that our justice systems recognize that.”

Probation Chief Terri McDonald agreed.

It was the department’s goal to have “trauma informed care” instituted in all the department’s facilities, said McDonald, who addressed the commission on Thursday along with Sherin, and other members of her command staff, plus two DMH staff psychiatrists.

“But we haven’t rolled it out as fast as we want to,” she admitted.

The LA Model

McDonald brought up Campus Kilpatrick, the $58 million facility the department opened in the hills above Malibu last July. Kilpatrick, with it’s soothing colors and community college-esque design, was billed in its planning stages as “a vehicle to bring LA’s juvenile justice system into the 21st century.” It would purportedly do so by piloting a therapeutic, research-guided, “trauma-informed” environment that helps and heals, not punishes, kids who wind up in one of the county’s youth lock-ups.

Now that Kilpatrick has been open for more than six months with generally good reviews (more on that in an upcoming story), the department intends to implement versions of the same model in the county’s other youth camps and halls. But implementing such a fundamental cultural change department-wide, has not been an easy task, McDonald admitted.

Chief McDonald, and her second in command, Assistant Chief Probation Officer Sheila Mitchell, who heads up the department’s juvenile division, have just passed the one year anniversary since they were appointed by the board of supervisors to run the nation’s largest probation agency. Although they have their critics, many department watchers make a point of praising both women, plus those who work closely with them, as having made measurable progress in addressing the mountains of problems McDonald and Mitchell faced when they each began in January of 2017.

But some mountains, it seems, are more complicated to move than others. Instituting trauma informed care, and the LA Model, outside the confines of the long-awaited Kilpatrick, is evidently one of those harder to budge peaks.

It is at the top of Sheila Mitchell’s list of priorities, said the chief, yet the going has been slow.

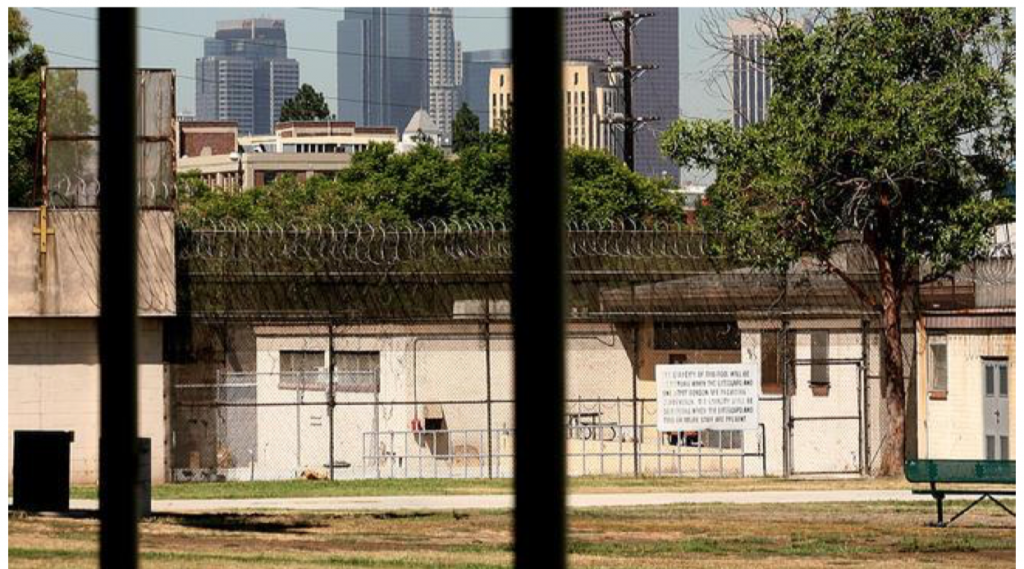

“We have been trying to get it out piecemeal to the facilities where we’re having [the most] problems,” McDonald said. High on that list is Central Juvenile Hall, the county’s sprawling and decrepit facility located next door to LA’s main juvenile court on Eastlake Avenue, northeast of downtown.

“Dr. Sherin and I went to CJH recently, and had a briefing with the clinical personnel,” said McDonald. “They were as traumatized as the kids are.”

(We should likely note here that WitnessLA has reported multiple times on the rapidly expanding body of research indicating that youth who wind up in the nation’s juvenile justice systems show a significantly higher degree of exposure to severe childhood trauma, such as maltreatment, the witnessing of violence, and personal victimization such as physical abuse and/or sexual abuse, than do kids outside the system.)

Trauma and environment

According to Chief McDonald, one of the issues with central juvenile hall is the physical plant, which looks unattractively prison-like and is, in a number of areas, falling apart.

“We have to create a healing environment for the kids for the staff there,” said the chief, which likely means the county will eventually need to cough up some serious money.

“With Central Juvenile Hall we’re going to try to get the board to invest in replacing that facility with a treatment center,” said McDonald. “In the interim we’re trying to go around and upgrade [the hall’s] housing units.” They’ve already done some renovation to the boys care unit.

“We’re just waiting for the furniture to be delivered. Chief Mitchell is going unit by unit, trying to create a more normalized more trauma-informed environment,” McDonald said, then paused. “But we’ve got a lot of work to do.”

A big element of that “work” is putting the probation staff assigned to the camps and the halls through the kind of rigorous “trauma-training curriculum” that the staff at Kilpatrick have already received.

The urgent matter of training

It was Chief Sheila Mitchell who gave the commission an updated status report on the issue of trauma-focused staff training, particularly as it related to the department’s three juvenile halls.

“Most of the kids who come to us,” she said, “are highly traumatized.”

So in developing a trauma-informed system of care, what the department needs to do, Mitchell said, “is to make sure that all parties who are responding to these youth—meaning DMH staff, LACOE (Los Angeles County Office of Education), and probation— are responding to the impact of what kids are faced with in terms of trauma.”

And all that requires in-depth training.

Evidently, however, the curriculum needed for the department’s front line juvenile officers isn’t a one-size-fits-all matter, but must be tailored for each of the various types of facilities. For instance, Mitchell said, training for the detention officers who work in the juvenile halls is, of necessity, different because so many of the kids who come to the halls are there for very short periods. Yet, other kids, like those in certain units at Barry J. Nidorf juvenile hall in Sylmar, may be staying for very long periods, while they fight serious criminal cases.

Thus probation has a team, many of whom worked with the staff at Kilpatrick, that is working on designing the right program for staff at the various juvenile halls, said Luis Dominguez, Acting Deputy Director for the department’s Detention Services Bureau.

Although the implementation of the training, as McDonald said, has not been speedy, some progress has been made, according to Mitchell and Dominguez. For instance, The staff at Dorthy Kirby Center, the department’s intensive treatment facility located in Commerce, has already received their first round of trauma-informed instruction.

In the meantime, the higher ups are attempting to keep the youth populations in the facilities low, “and our staff-to-youth ratio high,” said Acting Deputy Chief Dave Mitchell. “It’s a lot easier to treat kids when you only have 40 or 50 kids in a facility, instead of 100 or a 120,” he said.

Part of keeping our population low, added Sheila Mitchell, “is looking at who is coming in our front door” to see if the youth coming in that door “really need to be there to begin with. Are they high needs and high risk? Or are they just high need, which is often the case with some of our girls, who may not need to be here at all,” she said. “And [that issue] is not something that should be treated lightly.”

Dr. Sherin went further, and told the commission that keeping kids out of probation facilities altogether is the most desirable outcome.

“When we have kids who enter this system,” he said, “it’s critical that we provide normalizing, nurturing environments in the halls and the camps.”

But, added Sherin, “we need to really, really need to work upstream of those systems [foster care and probation]” to identify kids far earlier who are reaching out for help. Right now,” he said, “we don’t identify and act on those red flags in a very proactive or robust way.”

The county’s goal must be to set up a system, according to Sharin, that connects DMH, probation, the foster care system, and community groups in order to push out resources and support to kids earlier “so they will not act out and be punished when they are actually asking for help and care.”

And so it goes. As is often the case, genuine change comes slowly.

Top photo, left to right, Probation Chief Terri McDonald, Dr. Jonathan Sherin, director of DMH, also from DMH, Dr. Hanumantha Damerla, and Dr. Christopher Thompson. Photo by WLA

For some reason I start thinking of the Music Man and Professor Harold Hill character looking at this photo. Flem flam, sham, smoke and mirrors, speaking with forked tongue, there’s a sucker born every minute are just a few amongst the many other colorful descriptors that come to mind.