Is Los Angeles County about to underfund its most important diversion programs, particularly when it comes to mental health diversion?

A new letter sent to the members of LA County Board of Supervisors from the ACLU of Southern California says that is exactly what is about to happen this coming Tuesday, September 29, unless changes are made in the county’s supplemental budget, which is about to come up for a vote.

Furthermore, according to the letter, this underfunding potentially exposes the county to future high ticket lawsuits. (Just in case the board is interested.)

But before we get to the details of the ACLU letter, and the problems it flags, first a little background on the topic of diversion, and related issues.

As WitnessLA has reported in the past, in January of this year, the nonprofit RAND Corporation released an important study which concluded that approximately 61 percent of the mental health population locked inside Los Angeles County’s jail system were appropriate candidates for diversion, meaning they could safely be released into community-based care.

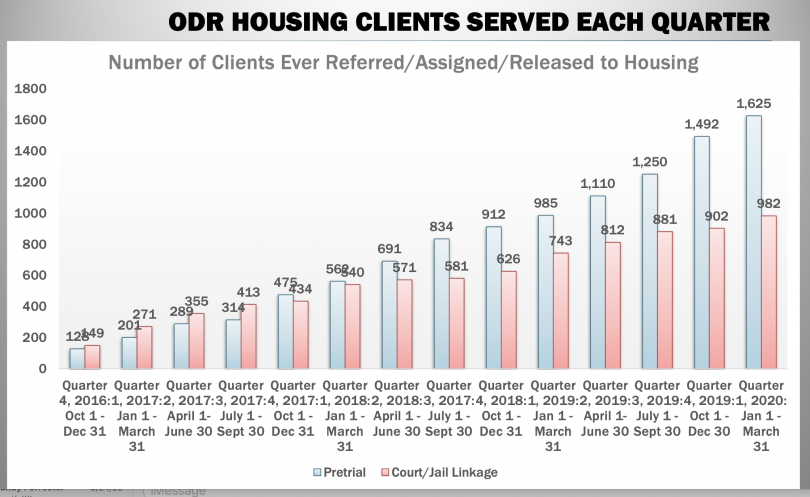

Just to remind you, the Office of Diversion and Reentry Division (ODR), was created in 2015 to redirect individuals with serious mental illness challenges from the criminal justice system. Part of the mission of the ODR, which operates under the LA County Department of Health Services and is run by former judge Peter Espinoza, is to identify individuals currently incarcerated in the county’s large jail system, “who are experiencing a serious mental health disorder.”

Then, if at all possible, the ODR provides those individual with appropriate community-based care, with the goals of reducing their likelihood of future encounters with the justice system, and improving individual health outcomes — and general life outcomes — for the various individuals, both adults and youth.

As of June 2019, according to the RAND numbers, there were 5,544 people suffering from mental illness incarcerated in LA County’s jails, which was about 30 percent of the total jail population.

(RAND’s count included those being held in mental health housing units, and those taking psychotropic medications, who were not in the specialized units.)

This meant, according to RANDs January report, that around 3,368 of the 5,544 people in the jail system’s mental health population would likely do better somewhere other than behind bars.

“There are quite a high number of people in our jails every day who are not there because they actually pose a great risk to public safety, but because their offense was committed through some aspect of their mental illness,” said LA County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl in January after the report came out. “Most of these people don’t actually need to be in jail, Kuehl said. “We certainly know” that jailing people with mental illness doesn’t improve recidivism rates.”

In the past year, the board of supervisors has repeatedly endorsed the necessity of addressing these and related issues with a number of motions.

To use a prominent example, in mid-August of 2019, the board voted to cancel the $1.7 billion contract to replace the dangerous and dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail, and to commit to a “care first” ethic for the mentally ill.

In February of that same year, the board demonstrated its philosophical commitment to this care first perspective, when it asked the Office of the CEO to create “a public-private county work group” to explore Alternatives to Incarceration, or ATI, as it has now become known.

Alternatives to Incarceration

Specifically, the ATI group was to be charged with developing a “road map, with an action-oriented framework and implementation plan,” to scale alternatives to incarceration and diversion so care and services are provided first, and jail is a last resort.

At their March 9, 2020, meeting, the board voted to adopt the ATI’s five main strategies — and asked the county CEO to take the initial steps of instituting a larger plan designed to make the ATI’s recommendations a reality.

But then COVID-19 hit in earnest that same month, and Los Angeles County, along with most of the state’s other 57 counties and California itself, took a series of pandemic-related fiscal body blows.

This, in turn, caused a lot of former budgetary must-do’s to get slashed. Some of that slashing is set to be rewound when the board votes on Tuesday to approve the interim CEO’s supplemental budget.

Meanwhile, the number of people with mental illness in LA’s county’s jails is reportedly higher than it was at the time of the release of the RAND report in January, meaning that the number of those eligible for diversion, is also likely higher.

Specifically, on September 22, 2020 there were 5,743 in the jail’s mental health population, up from about 200 individual since the 5,544 people flagged in the RAND report. In addition to a rise in the raw numbers, the mental health population now comprises a larger portion of the LA jails population as a whole, than it did earlier this year.

On February, before the sheriff’s department began COVID-related releases, the jail system population was 17,156, of which the mental health population comprised 34.4 %.

Less than a week ago, the total jails population was 14,707, but the mental health population was 5,743, which means it now comprises almost 41% of the total jail population, not the previous 34%.

In other words, the ODR and its diversion capabilities are badly needed now, more than ever.

The ACLU points to the problem

All this brings us back to the letter sent to the members of the board of supervisors on Thursday, September 24, by the ACLU of Southern California — plus a group of co-signers from the disability rights community, including Disability Rights California, Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, and the Judge Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law — telling the board that the county is about to disasterously drop the ball when it comes to funding for mental health diversion, unless it makes some changes quickly.

This is happening, the group says, even though the board understands that diversion programs, which provide people with appropriate community services, not only lead to significantly improved outcomes for the individuals involved,” they “also lead to lower incarceration rates and lower county costs.”

“In response to COVID,” writes Eliasberg, “the County has appropriately made efforts to release people from jail. But, these efforts have left people with mental health disabilities behind.”

With all this in mind, the ACLU and co-signers have called on the county’s interim CEO to find an additional $30 million, which will allow the county’s Office of Diversion and Reentry to expand its diversion work, the success of which is closely intertwined with many of the other potentially transformative initiatives, which the board supports.

So, where will the cash come from for additional ODR funding?

Well, according to Eliasberg and the rest, diverting just 500 people from LA’s jails — plus from the county’s youth camps and juvenile halls — will “reduce workload” on both LA County Probation and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. “So perhaps a few small fiscal slashes from those two agencies’ still sizable budgets would help the CEO ” find $30 million,” for the ODR, writes Eliasberg.

And in case the above points don’t persuade the board and the interim CEO to raise the ODR’s new budget, the ACLU and its co-signers point out that “that the failure to fund expanded diversion efforts is inconsistent with the ADA [the Americans With Disabilities Act]” which could put LA County at risk legally.

In other words, county officials might wish to think about the possibility of future high ticket civil rights lawsuits if they don’t get with the program on Tuesday, when it comes to making sure that diversion gets what it needs.

“We’re bringing that fact to the Supervisors’ attention in the context of this budget vote,” Eliasberg writes pleasantly.

The ODR, women, and race

The demands outlined in the ACLU’s letter seem especially essential crucial if the county intends to move ahead on the changes detailed in the Alternatives to Incarceration workgroup’s five primary strategies, to which the board has repeatedly said it is committed.

“The jail setting, exacerbates many symptoms of mental illness and prevents those who most desperately need medical, mental health, and/ or substance use treatment from receiving it,” the ATI report notes. “There is often an overlap between those suffering from severe mental health and/or substance use disorders and chronic homelessness.”

Furthermore, this issue disproportionately affects women, according to ATI report (and multiple other reports).

Around half of all women in the LA County jail are considered part of the “mental health population, wrote the ATI authors. “As of 2015, the rate of mental illness in the jail is significantly higher for women (27%) than for men (19%), and this disparity continues to grow.”

The ACLU letter adds that an underfunding of mental health diversion disproportionately affects Black jail residents, who “comprise about 41% of the jail mental health population,” which is far above their percentage of the overall jail population. (For more on the above issue, see this August 2020 study.)

Right now, the county’s supplemental budget will only fund “current operations,” he said.

“Meanwhile, 5,000 people with mental health diagnoses who could be diverted are sitting in jail in a COVID-unsafe environment, because ODR has not been provided additional resources to provide housing and services to them.

“It’s great that the county says it’s moving in this new direction, but why is it failing to adequately fund the ODR?”

Why indeed.

Postscript

We’ll have more shortly about whether or not the county will or won’t adequately fund the Alternatives to Incarceration initiative. So, stay tuned.