By Rebecca Beitsch

Mike Anderson was an 18-year-old freshman at Texas State University when he was busted with less than a gram of weed. Police arrested him, took his mugshot, and he spent the night in jail.

The legal consequences for being caught with such a small amount of marijuana — just enough for a joint or two — were minimal, but expensive. Prosecutors offered to drop the charges if he attended a drug program and did community service, and he could later get the record of his arrest expunged for about $500, wiping the history of his arrest from public view.

“After I got it expunged I thought it was pretty much a done deal,” he said of the order granted earlier this year.

But the next time he Googled his name, he realized the ordeal was far from over. His arrest photo was posted on Mugshots.com. The page was one of the top results for anyone who might be looking for him. And as Anderson applied for internships — a graduation requirement for mechanical engineering majors — recruiters who initially seemed interested would offer the spot to someone else.

“It wasn’t right,” said Anderson, a junior, who asked that his real name not be used for fear of drawing further attention to his mugshot.

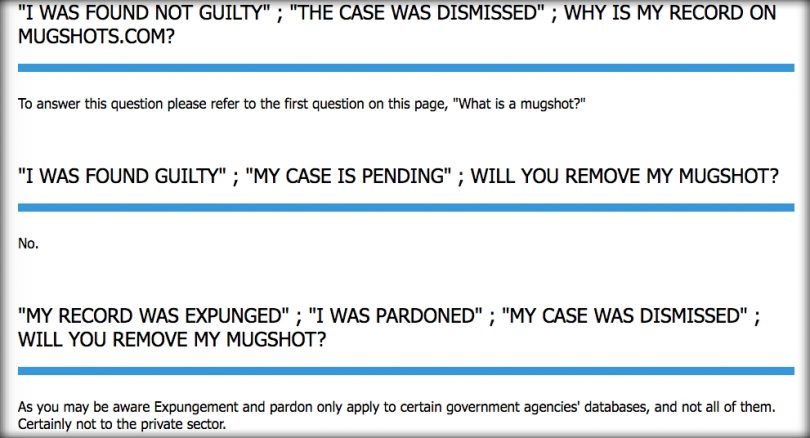

“I called [Mugshots.com] on the phone, and they told me basically the only way I could get the mugshot to come down was to pay a certain fine. Proof of expunction wasn’t valid.”

At a time when personal information can end up online and rocket around the globe in seconds, the estimated 78 million Americans with criminal records are a rich target for websites that collect mugshots from police departments and sheriffs’ offices across the country and typically charge hundreds or thousands of dollars to have the photos removed. Even people who are arrested but never charged have their photos on the sites.

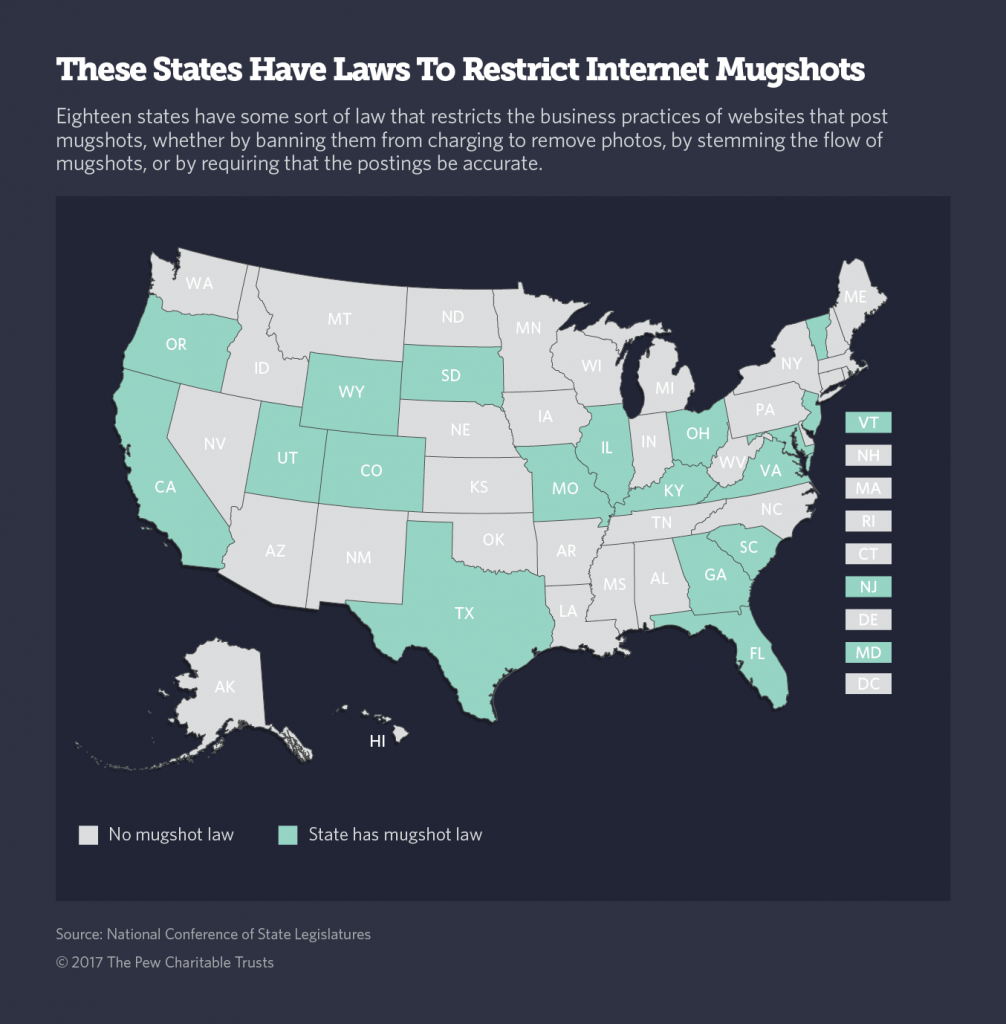

Since their business practices came to light in 2013, the websites have drawn the ire of state lawmakers who criticize them as exploitative. Texas is one of 18 states with laws designed to help people like Anderson, cracking down on mugshot websites by banning them from charging removal fees, stemming the flow of mugshots from law enforcement agencies, or requiring that the postings be accurate.

But so far, the laws have been largely ineffective in providing relief to those whose photos are featured on the sites.

“They haven’t worked,” said Eumi Lee, a law professor at University of California-Hastings who has spent three years studying the effectiveness of mugshot laws for an upcoming legal review article to be published by Rutgers. “But they’ve had a bunch of unintended consequences.”

Mugshot websites have ignored the laws or quickly figured out ways to work around them, Lee said. In places where people can no longer pay to have photos deleted, they often have no remedy to get them removed. And once law enforcement releases the photos, they have little control over where they end up.

Mugshots.com, one of the biggest purveyors, has entries for nearly 30 million people, including people in states that hoped to make it easier to have mugshots removed.

A Stateline review found evidence across the country of the laws’ inadequacy:

- Georgia twice tried to get mugshots off websites, first blocking sites from charging arrestees who were never convicted to have their pictures removed, and then requiring affidavits from any entity requesting law enforcement copies of mugshots. Still, Mugshots.com claims to have 2.3 million records from Georgia on its site, including entries for those arrested after the law took effect.

- California enacted a law in 2014 barring mugshot companies from charging to remove photos. But even its sponsor doesn’t know how well it’s working. Pressed recently by Stateline for evidence of the law’s effectiveness, the office of state Sen. Jerry Hill, a Democrat, found a still-operating site, Whogotarrested.org, requesting a fee to remove photos. He requested a probe by the state’s attorney general.

- And in Illinois, where the law similarly bans fees to remove mugshots, Mugshots.com is being sued for charging arrestees.

One of the plaintiffs in the Illinois suit, Peter Gabiola, said he can’t escape a criminal past — despite time served — because his face keeps popping up on Google searches. Gabiola said Mugshots.com told him it would cost $15,000 to have his information removed from the site. He contends he’s repeatedly been fired shortly after starting new jobs, even when he disclosed his criminal past, because Mugshots.com incorrectly insists he is still on parole.

“I made my life hard enough making some of the decisions I made in the past as a knucklehead, so I don’t need some worldwide company or whatever making it harder by publishing incorrect information,” Gabiola said.

Sheryl Ring, Gabiola’s attorney, said that’s part of the company’s business model — people who are already struggling because of a criminal record will be more likely to pay if the listing makes things look worse than they really are.

Despite the laws’ dubious track records, states keep enacting them. This year Florida, New Jersey, Ohio and South Dakota all enacted laws targeting mugshot websites.

To be sure, trying to rein in mugshot websites is a challenge. In most states, mugshots are a public record. The companies can digitally scrape the photos from law enforcement websites, uploading them to their own sites in just hours, or put in public information requests to get others. When they’ve been sued, the sites’ attorneys have repeatedly argued their work is protected under the First Amendment.

Among those who defend putting mugshots online are newspaper publishers, whose sites often feature local mugshots in crime coverage.

David Ferrucci, an attorney for Mugshots.com, said people featured on the site are being harmed not by the website but rather by their own criminal history.

“If your claim is that the publication of public records has hurt your reputation, then you’re complaining about the publishing of public records,” Ferrucci said.

Most of the state mugshot laws include some sort of criminal component, typically making it a misdemeanor offense for not complying. But it’s not clear that police have ever filed charges against a mugshot website. The onus falls almost entirely on the person whose photo is posted, and lawsuits are no small undertaking, particularly for those who cannot afford an attorney.

“It’s just like anything else. It’s against the law to murder somebody, but people get murdered every day,” said Georgia state Rep. Roger Bruce, a Democrat who sponsored both of the laws Georgia enacted to address mugshot websites. “But now the law is on their side. They can get an attorney and go after whoever posted their mugshot.”

A Stateline review of federal court dockets showed about 10 lawsuits in five states, many of which have come from people defending themselves in court. Several cases taken on by bigger law firms have stalled in court, complicated by an inability to get class certification or fears the firm would not ultimately see much money from the case, lawyers involved in the cases said.

Catch-22

Gabiola’s suit in Illinois is one of the first using a state law that bars mugshot websites from charging people to remove their photo from the site. Among others upset at the website is Terrill Swift, who spent 15 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit and whose photo is still on Mugshots.com five years later.

“They should do the right thing and take our pictures off those websites,” Swift told the Chicago Tribune earlier this year.

Both the lawyer for Mugshots.com and supporters of the law say it puts arrestees whose photos are on the site in a bit of a Catch-22 — they can no longer be charged to remove photos, but they don’t have a legal avenue to get them removed from the site. So Mugshots.com can keep them up.

“Perhaps the cruel irony of the Illinois law is that people who previously were able to have the information removed can no longer do so,” said Ferrucci, the Mugshots.com attorney.

Mugshots.com tried to get the case dismissed on First Amendment grounds, but a U.S. district judge denied the request. Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, a Democrat, intervened in the case in favor of Gabiola, saying Mugshots.com was engaged in an “extortionate practice” not protected by the First Amendment.

Ring, Gabiola’s attorney, says it’s already clear that mere passage of the laws does little to change the companies’ business practices.

“In terms of whether these statutes are effective, we’re going to need to find out if courts will actually enforce them,” Ring said.

If the suit gets class certified, the $1,000 in damages provided by state law could require Mugshots.com to pay out millions.

Finding Workarounds

In Texas, Mugshots.com refused to take down Anderson’s photo without a $300 payment, even though state law requires that mugshot sites jibe with the state’s criminal records — and according to Texas, he doesn’t have one.

Kelvin Bass, an aide to Democratic state Sen. Royce West, who helped craft the state’s mugshot law, acknowledged it doesn’t have a good enforcement mechanism. He’d like to amend the law to put more pressure on the attorney general or local law enforcement agencies to take action.

“This guy’s a college student,” Bass said. “Why should he have to sue to get someone to follow the law when he’s already notified this business that they’re in violation? It should be easier.”

Kayleigh Lovvorn, a spokeswoman with the Texas Attorney General’s Office, said the office has received 19 complaints against Mugshots.com, but the state has taken no legal action against the company.

Sponsors of mugshot laws in several states say they haven’t kept a watchful eye on the laws’ effects, but they’ve been contacted by people who say they’ve been helped by their passage. They say the laws aren’t intended to shut down the websites, just to curb their extortive practices.

But they also say mugshot sites have found workarounds: Attempts to block payment are often ignored, and sites can still make money off ad revenue. Even when mugshots aren’t released, the websites use old arrest photos or mugshots from when people are booked in prison. The private sector has tried to step in; Google tried to change its analytics so mugshot websites aren’t among the first to surface in a name search, but the mugshot sites can game the new algorithms.

Lee, the professor studying mugshot laws, thinks the only way to stop improper use of the photos is to stop releasing them at all, even to the media, ceasing their designation as a public record.

“It completely undermines the efficacy of those efforts,” she said of the laws.

Federal mugshots have largely not been available since 2016, when the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the Detroit Free Press, which wanted access to the photos. But even some who want to crack down on the sites are hesitant to go that far.

“Arrest information is always public, and I don’t know if we want to prohibit that,” said Hill, the state senator from California. “We start sounding like a totalitarian state where people are secretly arrested and no one knows about it. No one can react to it or take action.”

Back in Texas, Anderson continues his search for the internship he will need to graduate.

“I’m a junior right now, and I have about a year left,” he said, but “once a company searches my name, I just don’t get the same attention I did before.”

Rebecca Beitsch is a staff writer for Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Image: Mugshots.com

A mugshot photo is as much public record as the court documents the LA times and other news organizations get to write their news stories. Can’t have it both ways…