On Tuesday, Nov. 19, a coalition of community organizations called Let’s Get Free LA, presented the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors with a 30-page report calling for an end to the use of dozens of criminal justice system fines and fees in LA that disproportionately burden low-income families and communities of color.

The coalition is made up of the ACLU of Southern California, the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, the Community Coalition, Homeboy Industries, the National Lawyers Guild-LA, Public Counsel, and the Youth Justice Coalition, and criminal system-impacted people.

Some of those people weighed down by the outsized financial burden of the maze of administrative fees and penalties showed up to the meeting to urge the board to not only eliminate the fine and fee systems, but to also wipe the ongoing debts of those from whom the county has tried to collect. Some even called on the board to return money to those who had already paid for their entanglement with the criminal legal system.

Community Coalition’s Belen Flores called on the board members to get rid of the fines and fees “that are impacting grandmothers, mothers, [and] partners” of criminal justice system-involved people. “A lot of us are overwhelmingly women of color, low income,” she said. The fees are “stifling our communities more than anything.”

Indeed, in 2015, a national report from the Ella Baker Center revealed that of those family members specifically responsible for the costs associated with a loved one’s incarceration, including court fees and fines, a whopping 83% were women.

Among the other alarming bits of information from the survey of more than 2,000 people in 14 states, was the news that a fifth of respondents said they were forced to take out a loan to cover incarceration costs.

A separate UCLA Million Dollar Hoods study found that 43 percent of the people the LAPD arrested between 2012 and 2017 were unemployed.

Fines and fees follow individuals out of jail and back into their communities, where they make successful reentry all the more challenging to achieve.

“Criminal system debt makes [reentry] even more difficult by making people ineligible for record-clearing and by damaging people’s credit reports, eliminating opportunities to secure jobs, housing, and commercial leases or loans,” says the report. “Status hearings to enforce fees payments disrupt work schedules, making it hard for people who owe such debt to hold down jobs. Research and anecdotal evidence shows that fees often push people into the underground economy in order to make their payments to the county or court and still make ends meet.”

In its report, Let’s Get Free LA argues that these fines and fees entrap people in a cycle of debt and criminalization, all for a minimal financial benefit to the county.

In January 2019, an LA County Probation Department report revealed that the department had collected just 3.8 percent of the fines and fees it imposed on adults under its supervision.

Every year it spends an astonishing amount of money to hound probationers for that 3.8 percent.

LA County’s probation system is the largest in the nation with 57,000 adult probationers, and an annual budget of more than $850 million.

Yet Los Angeles County dedicates over $4 million of those funds “to staff probation collection efforts — more than the total probation supervision fees collected,” the report says.

The costs levied against people who come into contact with the criminal legal system — from jails, to courts, to probation — include public defender fees, probation supervision fees, penalty assessments, lab fees, drug test fees, various processing and service charges and surcharges, and more.

“I could not believe that I had to pay for my own probation supervision — a program that didn’t help me find a job or get into school,” said Anthony Robles, a young man whose story of being shackled to justice system fines and fees ($4,000 for probation, for example) after his actual incarceration, is included in the report. “Probation never offered bus passes, access to computers, or life counseling. It was my struggling family who provided that support.”

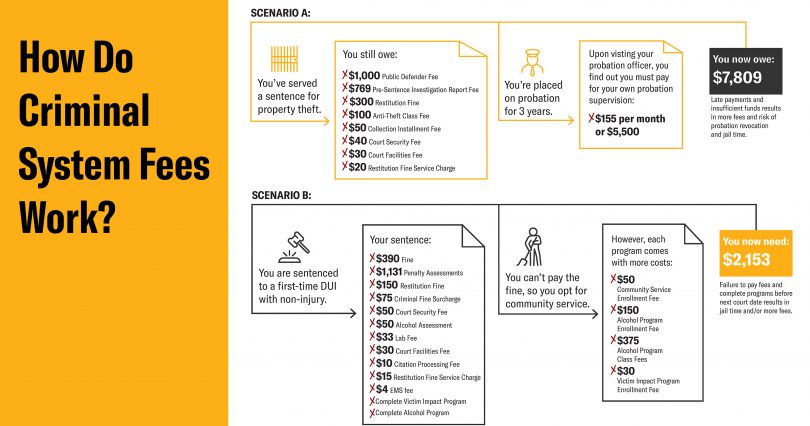

In addition to the stories of financial hardships faced by Robles and other Angelenos, Tuesday’s report lays out a couple of possible scenarios. In one, a first-time DUI fine of $390 balloons into more than $2,000 in debt, with 10 other administrative and penalty fees tacked on.

Even the alternative — community service — requires payment to participate.

One woman, Erica M., told the board that she was assigned 70 hours of community service — an untenable number of free labor hours for a woman who works a minimum wage job and already served her time in jail. And the community service hasn’t even freed her from having to pay up. “I have to choose between groceries and paying the fines,” Erica said.

“I have seen people,” said Youth Justice Coalition’s Kim McGill, “with 900 hours of community service.” That’s 22 weeks — or 5 months — of full-time work.

In LA County, more than 100,000 people register for community service every year, and perform approximately 8 million hours of unprotected free labor, according to a UCLA report released last month. Court-ordered community service, the report says, amounts to little more than “a fundamentally coercive system situated at the intersection of mass incarceration and economic inequality, with the most profound effects on communities of color.”

Community service is often portrayed as a progressive alternative to incarceration and court fees, but it, too, pushes people deeper into the criminal justice system when they can’t either finish all the hours on deadline or pay the rest of their debt.

And when people can’t pay their justice system debts, they often face extended probation or lockup. This system amounts to a debtor’s prison pipeline, the report says.

Not only does this strategy have a severely detrimental impact on individuals, but milking low-income Angelenos and their families for cash burdens the very systems the scheme is intended to fund, according to the report.

Court hearings triggered by a failure to pay fines and fees eat up “resources allocated to county public defenders, prosecutors, and the Probation Department, as well as to the court,” the report explained. Such a hearing can result in a court requiring someone to spend even more time on probation “for the purported purpose of giving the person time to demonstrate they can make consistent payments, to pressure them to pay fees, or to punish them for failing to pay fees.” And extending probation ultimately leads to even more fines and fees and an additional burden on Probation Dept. resources, while increasing the odds of a person returning to jail for a technical probation violation, according to the report.

If LA elects to cut justice fines and fees out of the local government funding equation, it will follow in the footsteps of Alameda County and San Francisco.

In 2018, SF leaders chose to get rid of a pile of fees that included an automatic, upfront $1,800 charge for probation supervision. The city-county then forgave $30 million in related debt that residents owed.

The Youth Justice Coalition successfully lobbied the Los Angeles County supervisors to get rid of fees and fines in the juvenile justice system in 2017. Los Angeles and a handful of other counties, including Alameda, Contra Costa, and Sacramento, Contra Costa, stopped passing juvenile justice system costs on to local families. (They joined San Francisco, which had never charged kids’ families such fees.)

In 2017, YJC, the Western Center on Law and Poverty, and the ACLU (among others) advocated for SB 190, CA Senator Holly Mitchell’s bill banning all 58 counties from charging for kids’ involvement in the juvenile justice system. Then-Governor Jerry Brown signed the bill on Oct. 11, 2017.

Earlier this year, Sen. Mitchell partnered with Sen. Bob Hertzberg to produce a follow-up bill that sought to end most administrative fees in the adult system, statewide. That bill, SB 144, also known as the Family Over Fees Act, failed to gain enough traction this past legislative season, but will be on the table again next year.

In the meantime, advocates and community organizations have focused their attention on Los Angeles County, which should “immediately eliminate all criminal system fees under county control, end their collection, and discharge previously assessed fees.” The county should also push for state-level reform by supporting SB 144, according to the report.

The coalition also recommends that the money the county will save on fee-collection should be redirected into community-based services, including cost-free diversion and rehabilitation programs. Additionally, the supes should create a system of oversight that ensures these criminal system program providers do not exploit families.

Finally, the report urges the county to “change policies and practices that lead to excessive pretrial time in detention, forcing plea deals that impose burdensome fees.”

The report stresses that LA County’s fee system is rooted in “past systems that have trapped people in detention, debt, and unpaid labor due to an inability to pay for freedom: debtors’ prisons, workhouses, and convict labor.”

Image by ACLU of Southern California.

More elimination of consequences for criminals means another step toward socialism. The taxpayers have a seemingly endless supply of money to take care of your pet miscreants.