A California bill would offer mentally incompetent juveniles held in detention the same legal protections as adults in the justice system.

With the deadline to sign legislation looming, California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) is considering a bill that would limit how long young people who are declared mentally unfit by a judge can be held in juvenile halls.

Assembly Bill 1214 seeks to prevent months- or years-long stays in halls as a result of mental incompetency. It would require counties to provide timely mental health services to stabilize these young people if possible. If not, most would be released to other placements. Those policies would be similar the protections now offered to adults during competency proceedings in the justice system.

Adults accused of a crime are provided mental health services to determine if their competency can be restored. If they are determined to be unfit for trial, those people must be given needed mental health services or placed in a mental health facility until they meet a standard of competency.

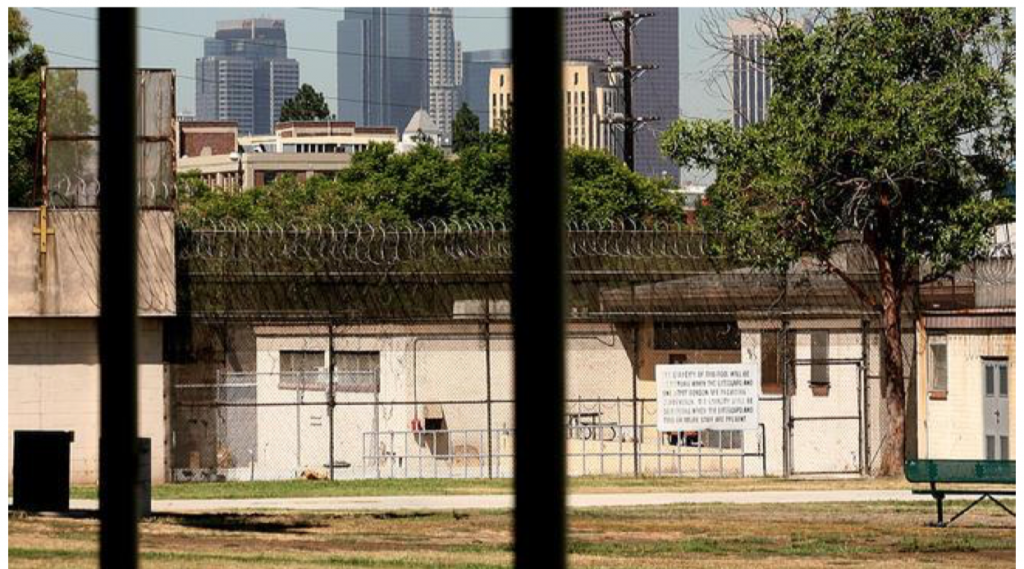

Delinquency courts in the state can declare young people who have been charged with a crime incompetent if they are dealing with significant mental health issues, developmental disabilities or developmental immaturity. But there is no cap on the length of time young people can spend in pre-trial incarceration, with few mental health treatment options available. According to supporters like the Chief Probation Officers of California, that has meant that a small subset of youth in California’s juvenile justice system are left to languish for months or years in facilities that are only meant for temporary stays.

Current competency procedures for juveniles neither improve public safety nor serve the youth in need of help,” said Assemblymember Mark Stone (D) in a statement to The Chronicle of Social Change. “This measure is necessary to improve the outcomes of juveniles and ensure that they aren’t languishing in juvenile halls when they should be receiving mental health services.”

AB 1214 would create a new set of court protections and timelines for youth who have been determined to be mentally incompetent. The bill hopes to resolve confusion in the current law around the type of mental health services that could be provided to youth and how long they would receive those services, according to Stone’s office.

Along with requiring mental health evaluations, the new legislation would require courts to regularly review the cases of youths who have been declared mentally incompetent — every 30 days for young people who are locked up and every 45 days for those youth who are being served in the community. If a youth does not achieve competency within six months, youths accused of less serious crimes would be released.

In addition to encouraging the court to consider alternatives to incarceration at juvenile halls, the legislation would allow courts to dismiss misdemeanor charges for mentally incompetent youths, bringing it in line with existing rules for adults.

According to San Francisco County Probation Chief Allen Nance, the issue of youth who stay at juvenile halls for long periods of time is a persistent issue for most probation departments across the state.

“Unfortunately, because of the way the current laws are written, a young person simply by virtue of their mental or developmental disability can end up spending far more time sitting in juvenile hall than they would if their matter were simply adjudicated and proceeded to a disposition,” said Nance, who works on juvenile services for CPOC. “Surely that can’t be the best California can do.”

Supporters have said the exact number of mentally incompetent youth in custody in the state is hard to come by. A report last year from Stone’s office estimated that about 300 of the approximately 7,000 youth in the state’s juvenile justice system were languishing in juvenile detention without adequate mental health support.

Nance said several young people have stayed for a year or longer in facilities in his county. When vulnerable youth are kept in juvenile halls for long periods of time, they don’t do well, and the odds they will become more deeply entrenched in the system only increases, he said.

“We know young people are much better off in the communities, where they can be linked to community supports, engage with families and are able to continue to thrive,” he said. “That is far more healthy and far more suitable than staying in our juvenile halls with uncertainty.”

Placing mentally incompetent youth in the community instead of in secure custody has brought criticism from several district attorney offices in the state.

In a letter of opposition signed by Los Angeles County District Attorney Jackie Lacey, public safety is cited as an important concern, along with funding to support mental health treatment.

“If a juvenile petition is dismissed, the juvenile, regardless of how dangerous or violent they may be, would likely be placed in an unsecured facility, which potentially places the family and community at risk,” the letter reads. “In those unsecured facilities…not only would the minor be free to leave, but the minor would present a dangerous risk to the other vulnerable youth in our dependency system.”

Gov. Brown also expressed qualms about public safety risk when he rejected a nearly identical version of the bill last year, sharing concerns about youth accused of “very serious crimes.”

At the end of this year’s legislative session in August, California lawmakers made several substantial revisions to the bill as they passed it out of both chambers of the legislature, including a new compromise to address those concerns about public safety. Now, the bill would ensure that youth charged with a serious or violent charge would be kept in secure confinement for up to additional year, for a total of 18 months, if it is “in the best interests of the minor and the public’s safety.”

Gov. Brown must quickly decide if the bill meets his standard for public safety. The last day for the governor to sign pieces of legislation is September 30.

Jeremy Loudenback is the child trauma editor for The Chronicle of Social Change, where this story first appeared. The Chronicle of Social Change is a national news outlet that covers issues affecting vulnerable children, youth and their families. Sign up for their newsletter or follow The Chronicle of Social Change on Facebook or Twitter.