Unlike their male counterparts, more incarcerated women are held in local jails than in state prisons, according to the Prison Policy Initiative’s latest annual “whole pie” analysis of the “231,000 women and girls incarcerated in the United States, and how they fit into the even broader picture of correctional control.”

PPI’s yearly “big-picture view of incarcerated women helps us see why many recent criminal justice reforms are failing to reduce women’s incarceration,” says report author Aleks Kajstura.

Yet, exactly why women are more often jailed than imprisoned is not clear. We just don’t have all the data we need to understand the issue fully, Kajstura says. “… Data on women has long been obscured by the larger scale of men’s incarceration,” according to the report.

But among the goals of the annual “whole pie” look at how and why women are locked up, is to help to ensure that “women are not left behind” in the push to end mass incarceration.

The report reveals the critical need for local reforms that will keep more women out of jail. As state-level reforms take shape and work to reduce prison populations, the majority of incarcerated women sit in county jails, where they have access to fewer rehabilitative, educational, and job-related programs, than women in prisons, as well as having more limited access to health care.

Not only are more women in jails than in prisons, but the number of women in jails grew between 2016 and 2017, indicating a “growing reliance on jails to solve social problems,” according to the report.

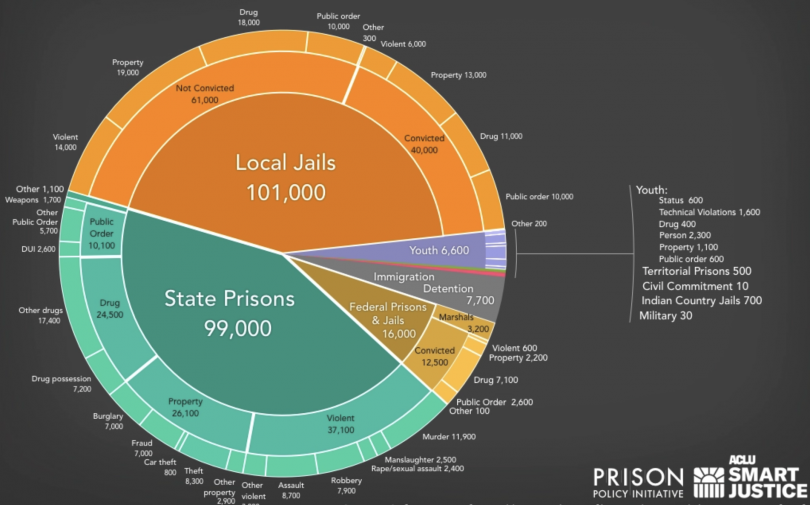

Approximately 60 percent of jailed women are being held pretrial, and thus have not been convicted of a crime. A startling 73 percent of women in jails and prisons have not been accused or convicted of a violent crime. In contrast, of the total national incarcerated adult population (most of whom are men), 57% have been not been accused or convicted of a violent crime.

The most common crimes for which women are locked in jails are property and drug crimes. Most common among women’s property crimes is fraud, followed by larceny/theft. And those women who are being held for drug crimes are most likely to be incarcerated for possession, rather than trafficking, according to PPI’s data.

Approximately 27 percent of incarcerated women are behind bars for violent crimes, including actions taken in self-defense against abusive spouses or partners.

While the population of jailed men declined from 2016 to 2017, the daily population of women in jail increased by more than 5 percent nationally. The increase cannot be explained easily – say, by increases in arrests, as arrest rates dropped slightly among women during that period. Instead, it is likely a combination of factors, which includes arrest rates, pretrial detention, longer case processing times, incarceration for probation or parole violations, or increases in jail sentences, the report states.

All that jail time carries significant costs to both women and their families, and taxpayers.

In January, UCLA’s Million Dollar Hoods Project put a price tag on jailing women in Los Angeles. According to their report, between 2010 and 2016, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department booked 173,023 women into county jail, at a cost to the county of at least $752 million.

A far greater number of pregnant women are sent to local jails than to prisons, according to yet another PPI study. And approximately 80 percent of 2.9 million women jailed each year are mothers. Around 150,000 are pregnant. Most are primary caregivers for their children.

In 2014, a UC Irvine study found that having a parent behind bars can be more damaging to a kid’s well-being than divorce or even the death of a parent. Students with incarcerated mothers and fathers are more likely to receive suspensions in school, and are more likely to drop out than their peers. Kids with incarcerated parents are also more likely to come into contact with the justice system, themselves.

And when mothers return from jail and prison, they are more likely than formerly incarcerated men to experience homelessness, unemployment, and other barriers to successful reentry. Yet most reentry programs are focused on the needs of the nation’s much higher population of justice system-involved men.

Get this and other essential justice stories delivered directly to your inbox by subscribing to The California Justice Report, WitnessLA’s weekly roundup of news and views from California and beyond. Read past editions – here.

For God’s sake, please quit whining about who and how many are incarcerated. Use your liberal Jedi mind tricks on your constituency before they commit crimes so they never end up victimizing society and don’t do any time.

[…] law only applies to federal prisoners and most prisoners are under state jurisdiction. Out of the 231,000 women and girls[5] in correctional facilities, only 16,000 of them are in federal prisons. States have passed laws […]