One out of four formerly incarcerated Americans over the age of 25 holds no high school diploma or GED–more than double the rate of their peers in the general public, according to a new report from Prison Policy Initiative, the third in a series exploring the difficulties people face while trying to access housing, employment, and education after incarceration.

People who have been in prison are far less likely to complete college—8 times less likely, in fact—than their non-justice-system-involved peers. While 29 percent of Americans complete a college degree, less than 4% of formerly incarcerated people hold a degree.

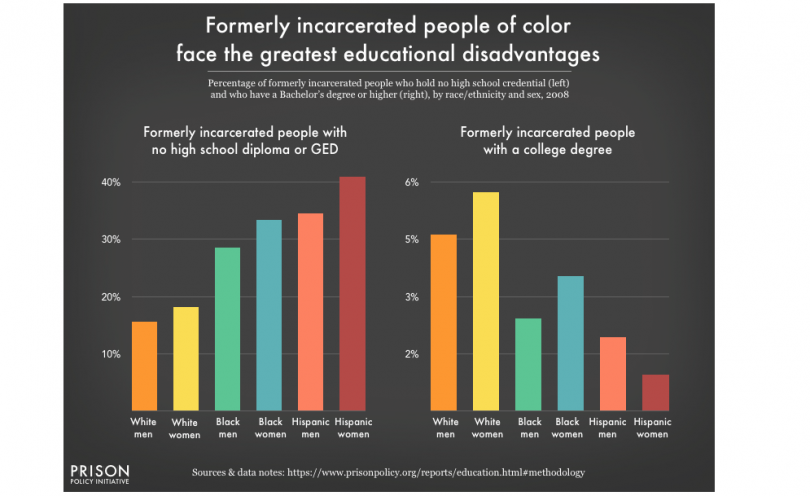

Educational disadvantages vary across genders and races. White men are most likely to have a high school diploma or GED upon release, while more than 40 percent of formerly incarcerated Hispanic women must navigate reentry without any high school completion credentials. And white formerly incarcerated women are most likely to earn a Bachelor’s Degree or higher (6 percent do), while less than 2 percent of formerly incarcerated Hispanic women graduate college.

GEDs are the most common method of high school completion among people who have been incarcerated, with 33 percent of formerly incarcerated individuals holding a GED. Three-quarters of those GEDs are obtained behind bars. Those who take the GED-route, however, miss out on the benefits that accompany four years of high school instruction.

Combined, the GED-earners and those with no diploma make up 58 percent of all formerly imprisoned people in America.

“Of course, an interruption in high school education does not necessarily lead to incarceration, and conversely, many incarcerated people have graduated from high school,” report author Lucius Couloute writes. “But such a low rate of high school completion among formerly incarcerated people adds to the body of evidence that overly punitive disciplinary policies and practices contribute to the criminalization — and ultimately, incarceration — of large numbers of youth.”

The lack of educational attainment feeds other post-incarceration problems, the most notable of which is employment.

The first study in PPI’s series revealed that formerly incarcerated individuals face a 27 percent unemployment rate. According to the latest report, people with lower levels of education completion experience even higher rates of unemployment post-incarceration.

The unemployment rates for formerly incarcerated people who lack a high school diploma or GED are 2 to 5 times higher than those of their peers in the general public. (The numbers range from 25 percent unemployment for white men to an alarmingly high 60 percent unemployment for black women.)

Part of the problem is that the percentage of what would be considered “low-skill” jobs that require only a high school diploma or GED, has been dropping since the 1970s.

Additionally, people with high school diplomas earn approximately 33 percent more than their peers with GEDs, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation.

“It is nearly impossible for formerly incarcerated job-seekers to compete in an economy that increasingly demands highly skilled, credentialed workers,” the report says.

And as the number of jobs requiring a college education increases, most people in American prisons have limited or no access to Pell Grants, federal loans, and programs that grant college degrees.

In order to remedy these educational disparities, the report calls for “a new and evidence-based policy framework that addresses K-12 schooling, prison education programs, and reentry systems.”

The United States should return the use of Pell Grants to justice-system-involved Americans, and do away with the legal barriers to financial aid that incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people face.

States should also “ban the box” on college applications. “Postsecondary educational institutions should give everyone a fair opportunity to pursue their educational goals, not further punish criminalized people looking to get their lives on track,” the report states. And prisons should offer “robust” educational programs. “Educational opportunities should be conceptualized as a means to begin the reentry process, not as a frivolous “extra,” says PPI.

We must also work to break down the inequalities in K-12 schools that contribute to low educational attainment “such as those arising out of zero-tolerance disciplinary policies,” the report says. “Students — particularly students of color — should not suffer from a lack of educational resources or overly punitive school policies that funnel them into prisons simply because of the neighborhood in which they live. In order for education to truly be the “great equalizer” it first has to operate equally.”