This week, the U.S. Supreme is going to be asked to grant a northern California deputy a special form of immunity from being sued by the parents of a 13-year-old boy that the deputy shot and killed in 2013, mistaking his pellet gun for an AK-47.

It will be an important and interesting legal matter to watch.

(There’s another equally intriguing case that the Supremes will decide whether or not to take later this week. But we’ll get to that other case in a minute.)

The shooting

Here’s the backstory on the 2013 matter of the deputy and the boy with the replica gun:

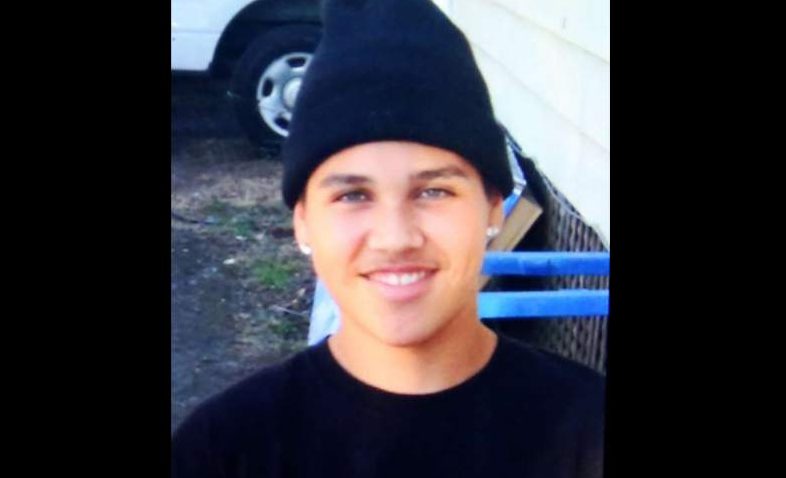

On October 22, 2013, a Sonoma County deputy fired eight shots in approximately ten seconds at a 13-year-old Santa Rosa boy who was walking down a residential street carrying a pellet gun. The boy, whose name was Andy Lopez, planned to return the airsoft-type gun to his friend who lived nearby, and was the gun’s owner.

The toy gun was shaped like an AK 47, but had no orange tip that distinguished it as a toy. The tip, it seems, had broken off prior to when Andy borrowed it, which reportedly worried the friend who had lent it to Andy.

As Andy walked to his friend’s home from his own house a few blocks away, according to the observation of two witnesses, the boy was carrying the gun in his left hand with the barrel pointing toward the ground. One witness observed the boy swinging the gun slightly as he walked.

That same day, Deputy Erick Gelhaus, a 24-year veteran of the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department, and an Army veteran, was training Michael Schemmel, who’d worked in law enforcement elsewhere, but had been hired by the Sonoma department just the month before. According to his own words, Gelhaus was hoping to give his trainee a more “proactive” experience that day.

The two had been on shift since 7 a.m. At approximately 3:14 p.m., the two deputies spotted 5-foot-3, 140 pound Andy Lopez, who was wearing a hoodie, walking on the west sidewalk of the street on which the deputies were driving northbound. Andy had his back to the deputies and was walking past a large vacant lot on his left, where kids often played (although it was empty at the time), proceeding toward his friend’s house.

Gelhaus called in a “Code 20,” which is used to request that all available units report immediately on an emergency basis.

There had been no reports of suspicious activity in the area, no radio reports at all, or any other triggering cause for concerns. The deputy’s actions from their radio call onward were precipitated solely by the sight of the boy walking up the residential sidewalk with what they believed to be a real gun, “walking away from us,” in Gelhaus’ words. Andy’s actions did not appear to be agressive.

In the following seconds, Schemmel, who was the driver, veered into the southbound lane and stopped at a forty-five degree angle facing toward the west sidewalk. According to his account, Schemmel also chirped the patrol car’s siren, although Gelhaus did not remember hearing the chirp. The boy, who was around 40 feet from the two officers, still with his back turned, did not respond to the sound, according to Gelhaus, but continued to walk at the same speed down the sidewalk, away from the deputies.

As their vehicle was slowing down, Gelhaus removed his seat belt, drew his weapon, and shoved the passenger side door open. When the car stopped, he launched himself out, and positioned himself squatting behind the open door of the squad car. Gelhaus shouted at least once at the boy to “drop the gun.”

According to both civilian witnesses, in response to the shout, Andy, who appeared previously to be unaware of the presence of the police, began to turn to his right, presumably to see who was shouting at him. He was still carrying the airsoft-type rifle in his left hand, according to Gelhaus.

The senior deputy reported later that the gun was being raised as Andy turned, with “the barrel of the weapon coming up,” according to one of Gelhaus’ accounts.

Later, Gelhaus conceded that he didn’t know if the gun was ever up or pointed his direction. And in a video demonstration by Gelhaus of how Andy held the gun when he turned, the deputy showed the boy’s gun consistently pointed at the ground, even after the turn.

In any case, Gelhaus fired his service weapon at Andy Lopez eight times, the first shots reportedly hitting his hand.

Seven bullets hit the boy. Three of the bullets remained lodged in his body. Several of the shots appear to have been fired after he fell to the ground.

Two of the shots were fatal, according to the coroner’s report. And one bullet went far past its target and lodged in a neighbor’s kitchen hutch.

Schemmel, as the driver, said he was not able to get into place until Gelhaus had stopped firing.

When, Gelhaus saw that Andy was no longer moving, Schemmel called in to say that shots had been fired, according to the DA’s 56-page report.

Other officers arrived on the scene quickly.

Andy Lopez was pronounced dead at the scene at 3:27 p.m..

He was a well-liked kid, and as many as 1,000 people, many of them school kids, attended a viewing of Lopez at a local funeral home the Sunday before his funeral.

His death also resulted in days of vigils and several large, but peaceful protests.

Legal actions and lack thereof

In early July, 2014, Sonoma County District Attorney Jill Ravitch announced the decision that her office would not file criminal charges against either of the deputies, and cleared both of any criminal wrongdoing.

As is often the case with high profile police shooting incidents where no criminal charges are filed, the family of Andy Lopez, proceeded with their civil suit against Deputy Gelhaus and Sonoma County, which they had filed earlier.

After some unsuccessful attempts to settle the lawsuit, in the fall of 2015, Sonoma County and Gelhaus filed a motion asking the federal court to shield the deputy from the lawsuit with “qualified immunity,” saying that his actions, while tragic in the outcome, did not violate anyone’s Fourth Amendment rights, as the plaintiff’s contended.

On January 20, U.S. District Court Judge Phyllis J. Hamilton ruled against the request for immunity writing that the court could “conclude only that the rifle barrel was beginning to rise; and given that it started in a position where it was pointed down at the ground, it could have been raised to a slightly-higher level without posing any threat to the officers.”

In light of that finding, according to Hamilton, a Bill Clinton appointee and the Chief United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, the record did not compel the conclusion that Gelhaus was threatened with imminent harm. Thus, a jury should decide whether or not the shooting was reasonable or violated Lopez’s civil rights.

The route to SCOTUS

After Judge Hamilton’s turn down, Deputy Gelhaus’s attorneys, and those of Sonoma County turned to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to shield Gelhaus from a jury trial.

In September of last year, the 9th Circuit upheld Judge Hamilton’s opinion, and ruled in a 2-1 split decision that there was “sufficient evidence that could lead a jury to conclude a Sonoma County sheriff’s deputy was not in imminent danger when he shot and killed a Santa Rosa teenager carrying a replica assault rifle in 2013.”

Deputy Gelhaus “also shot Andy without having warned Andy that such force would be used and without observing any aggressive behavior,” wrote Judge Milan D. Smith Jr., a George W. Bush appointee, in the majority ruling.

Furthermore, Smith wrote, “the district court’s finding is amply supported by the record. Gelhaus himself reenacted how Andy was holding the gun, “his turning motion,” and “what [Gelhaus] saw him do.”

The video, according to Smith, “depicts the gun in Gelhaus’s fully-extended arm and at his side as he turns, consistently pointed straight down towards the ground. Gelhaus also concedes that he does not know where Andy was pointing the rifle at the time that he was shot. Nor does Gelhaus know if Andy’s gun was ever actually pointed at him.”

Another element Smith noted in the 45-page ruling, was that one of the witnesses initially thought the gun Andy was carrying might be real, but “when he got within approximately fifty feet of Andy—which is further away than Gelhaus stood when Gelhaus first confronted Andy—he thought the gun “look[ed] fake.”

Judge J. Clifford Wallace, a Nixon appointee, disagreed.

“The facts of this case are tragic,” he wrote. “A boy lost his life— needlessly, as it turns out. We know now that he was carrying only a fake gun, albeit a realistic-looking one. Deputies Gelhaus and Schemmel therefore never were in any real danger and deadly force was not necessary. In view of these facts, the inclination to hold Deputy Gelhaus liable for shooting Andy Lopez is understandable. But it is a well- settled rule that a court may do so only if precedent clearly established at the time of the shooting that the use of deadly force in the circumstances Deputy Gelhaus faced was objectively unreasonable. I do not agree with the majority that such a case existed on the day Andy died. Respectfully, I therefore dissent.”

On March 22, Gelhaus and Sonoma County appealed the decision of the 9th to the U.S.Supreme Court.

Endangering the lives and safety of law enforcement officers

Several of the state’s law enforcement organizations supported Gelhaus’s entreaty to the Supremes with passionate amicus briefs.

For example, the lawyers for the Peace Officers Research Association of California (PORAC), wrote in their brief that the Ninth Circuit’s decision, “…would cause significant tentativeness on the part of officers facing life-threatening dangers.”

The decision, PORAC’s attorneys wrote, “implies that an officer must wait until a high-powered rifle is actually pointed at the officer before engaging a suspect, and that the use of force while the rifle is being raised may violate the Fourth Amendment rights of the suspect.”

Such a standard, PORAC concluded, “is unrealistic and would only serve to further endanger the lives and safety of law enforcement officers across the Ninth Circuit.”

Andy’s family also replied with an “Opposition to the Writ Of Certiorari, meaning the filing by Gelhaus, et al.

SCOTUS possible leanings

So will the Supremes go against the two lower federal courts?

Hard to say. Yet, given certain precedents, it is entirely possible that the nation’s highest court could be sympathetic to Gelhaus’s case.

“As this Court has repeatedly recognized,” the deputy’s attorney, Timothy T. Coates, wrote in a petition for writ of certiorari requesting immunity for Gelhaus, “officers are entitled to qualified immunity.. unless they violated a federal statutory or constitutional right, and the unlawfulness of their conduct was clearly established at the time of the events in question.”

To be clearly established, a legal principle must have a sufficiently clear foundation in then-existing precedent. The rule must be “settled law,” which means it is dictated by “controlling authority” or “a robust ‘consensus of cases of persuasive authority.’” It is not enough that the rule is suggested by then- existing precedent. The precedent must be clear enough that every reasonable official would interpret it to establish the particular rule the plaintiff seeks to apply. Otherwise, the rule is not one that “every reasonable official” would know.

Finally, attorney Coates concluded that, “in a post-Sandy Hook, post-Parkland world, “neither law enforcement officers nor the public they protect, have the luxury of assuming that someone in their mid to late teens carrying what appears to be an assault rifle on a sunny afternoon is more likely to be plinking cans with an illegal BB gun than presenting a credible threat of violence. This was a tragic incident, but under the governing decisions of this Court, Peti- tioner Gelhaus should not, and cannot, be held liable under the Fourth Amendment.”

The attorney for Andy Lopez’s family, Gerald Peters, naturally painted a very different legal picture.

“In this case, it is clear from at least three converging lines of established constitutional law” Peters wrote, that “Gelhaus violated Andy Lopez’s constitutional rights by shooting him seven times, resulting in Andy’s death.”

Peters then ticked off his three “converging lines,” along with SCOTUS rulings to support them.

• Ninth Circuit precedent established a body of law which clearly demonstrated it was not constitutionally permissible for Gelhaus to fatally shoot Andy Lopez since he presented no imminent threat to the deputies.

• Andy, a 13-year-old boy, who was de- scribed by passersby as “a kid” and “eleven or twelve years old,” was not an adult and could not, constitutionally, be treated as if he was an adult.

• Gelhaus violated clearly established law by shooting Andy, who was likely disabled by the first shot, which hit him in the upper left arm (the arm holding the toy rifle’s grip), six more times

There’s more to the arguments put forth by both sides, of course.

Yet, there are also couple of recent cases that suggest the high court could lean toward the law enforcement perspective.

Prominent among those cases worth examining, as David Savage from the LA Times pointed out, is a 2016 decision by the 9th Circuit to allow a trial to go ahead regarding a 2010 shooting of a knife-wielding mentally ill woman by a University of Arizona Police officer.

The majority of the the justices on the nation’s highest court disagreed.

“Police officer Andrew Kisela is entitled to qualified immunity because his actions did not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known,” the Supremes opined, on April 2018.

So, what will they do with this case?

We could know as soon as tomorrow.

Brendan Dassey, the Supremes, and false confessions

Another riveting and very important case that the U.S. Supreme Court will decide whether or not to take this week, is that of Brendan Dassey.

As those of you who were among the millions who watched the 2015 series, “Making a Murderer” are aware, one of the most disturbing elements of the show was the videotaped interrogation of then 16-year-old Dassey, the nephew of the show’s main character, Steven Avery.

Dassey’s halting, confused, and very frightened confession was virtually the only thing that supported his conviction and subsequent sentence to life in prison for the rape and murder of 25-year-old photographer, Teresa Halbach.

(Avery was also convicted of the rape and murder. Opinions on his guilt vary.)

On Thursday, the high court will decide whether or not to hear Mr. Dassey’s appeal.

According to an excellent story on the matter by the New York Times’ Adam Liptak, the court doesn’t usually take such cases. And yet, Liptak points out, “the court has long said that ‘the greatest care must be taken’ in making sure that confessions obtained from juveniles are voluntary.”

And Mr. Dassey’s case, Liptak writes, “could allow the justices to assess whether that command was taken seriously by courts in Wisconsin, which refused to suppress his confession.”

(WLA wrote about the problem of juveniles and false confessions most recently here.)

We’ll keep you up to date on both cases.

Under what is Objectively Reasonable (Graham V Tennessee) was the standard. The lower courts, especially the 9th, hasn’t a clue. The SCOTUS will determine that the shooting was Objectively Reasonable unless there are facts that are not in the article. The boy had very chance to drop the weapon and save his life. I do agree that toy guns should be painted some high tone florescence color. Whoever removed the orange tip knew that danger involved and that person should be held liable.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

“Um,” I’m in no way taking a side here on what the Supremes will or should do. But the 9th used Graham prominently in their ruling. Whether they got it right is very much at the heart of the matter, I agree. (It’s Graham v. Conner, by the way. You’re fusing Graham with Tennessee v. Garner, which was an earlier but related ruling.)

Thanks for bringing it up, though. (I was reluctant to get into case law, since this thing is already approaching novella length, and the dog needs a walk. But it was tempting, because it’s interesting—on both sides.)

For those readers who wonder what in the world we’re talking about, the precedent-setting cases in question are here: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/490/386.html and here: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/471/1.html

Happy Monday night.

C.

Such a tragedy on both sides.

Celeste:

“Um” posted his complaint at 8:53 pm and your response was at 9:12 pm. Quick work, and thanks for that.

On the Andy case, Points to Ponder:

1. Steven Mitchell was the lead attorney for Sonoma County on this case.

About a year and a half ago he drove out to the Sonoma Coast, parked his car, and swam out into the ocean.

His decomposed body washed ashore a few days later.

He was a high school valedictorian; his Baccalaureate was from Stanford University; and his Law Doctorate was from the University of California.

In other words, his shit was together.

He was the lead attorney for Sonoma County on the Andy case.

Full particulars can be Googled: Steven Mitchell, Sonoma County attorney.

2. Gelhaus was promoted to Sergeant, and he is now in charge of a crew of Deputies in the Sonoma Valley, one mountain range over from the Napa Valley.

He did in fact get the highest scores in the Civil Service promotional exams for the Sergeancy position.

Kudos to Celeste and to you Cognistator. Facts matter as it does require research, be it Google or the Law Library

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Dear Cognistator,

Thanks for the information. That’s so, so painful about Steven Mitchell. I had no idea. I saw in the line up of docs for the civil case that there was a change of attorneys notice part way through, and I wondered about it in passing. Now I know the reason.

C.

PS: I did indeed Google Mitchell, at your suggestion, and read the North Bay Business Journal story, which was very thoroughly, and heartbreakingly reported.

C.

No C: You have it wrong. We are talking about an armed fleeing suspect. And the 9th has it wrong also. Nothing new here. It’s Garner V Tennessee not Conner as I wrote, my mistake. The suspect, in the cited case, was a cat burglar and committed the crime while people were home, at night. He was seen with a pillow case full of the stolen items. At the time the PD had a policy that an officer could use deadly force if the suspect did not stop. This is important! The officer testified that he felt reasonably sure that the suspect was not armed. He followed policy but was wrong to shoot at a fleeing felon that posed no danger. Sandra Day O’Conner dissented and felt the shooting was according to law. I spoke to her about her decision in 2009 at a law lecture. She admitted that she was wrong. However, she was one of the best jurist on the SCOTUS. In this case the police were chasing an armed feeling felon and force was used.

Graham V Conner was case were two knuckleheads stopped at a store where the driver ran into the store and started running around hysterically(my words.) As I recall the suspect was in line and suddenly ran out of the store. Both suspects left the store at a high rate of speed. An officer saw the whole thing and pursued the suspects. The suspects stopped and the driver said that the passenger was diabetic and need something to eat. This would explain their behavior at the store. However,(another important point) there was no way the officer could know anything about the suspects and he didn’t have time to check at the store. One officer said to the suspect ‘Shut the F up” One suspect ends up with a broken arm and slammed against the hood of the patrol car. No crime at the store. There’s a lot more facts but you get the picture.The SCOTUS said the force was justified; as what was IN THE MIND OF THE OFFICER AT THE TIME WAS THE CRUCIAL POINT OF THE CASE!

Again, if the officer knew the gun was fake then liability is attached. According to the article there is nothing to suggest that the officer acted improperly. The kid’s age is not an issue in either case.

Last, if the decision stands then no one should become a cop!

Cog, how do you know his shit was together? Sometimes it only seems that way because of the type of work he did, where he went to school, the level of education he attained or his work rep. When one of the best officers, most street smart guys I ever worked with took his own life I couldn’t believe it. Rumors flew about why he did it and it wasn’t until about 3 years after that I found out why. Stress because he knew he’d fucked up big time and they had him. Not go to jail fucked up (close) but lose your job for sure and that was his life. Sorry this man came to this decision, just like my friend and two family members. Way too much of it going on, be cognizant of friends and family that seem off and take the time to reach out.

https://www.google.com/amp/www.northbaybusinessjournal.com/northbay/sonomacounty/5358738-181/lawyers-stunned-steve-mitchell-death%3fview=AMP

“Cog, how do you know his shit was together.”

That seems to be the consensus opinion of his work colleagues in the link you cited; this is the same citation that Celeste gave (North Bay Business Journal) in her response.

The last sentence in your citation probably says it all:

“He was a lawyer of great integrity.”

Outward appearances that people display to others doesn’t always paint the true picture of what’s going on with the person. Obviously his shit wasn’t together or he wouldn’t have taken his own life, man of integrity or not and I’m not disputing that he seemed to be. Tragedy for sure though.

Celeste!!!

In a ruling just now made (6-25-2018; Monday) the U.S. Supreme Court O.K.d a Civil Trial for Sgt. Erick Gelhaus.

Follow-up?

EDITOR’S NOTE:

“Cognistator!” Thank you for your info. (I checked on Friday, but hadn’t checked today!) Right now, I’m finishing a story that has to get out, but yes we need some kind of update! Thanks again for your eagle eye!

C.

PS: I just checked and see that, at the same time, SCOTUS has declined to hear Brendan Dassey’s appeal. Interesting. I’d have loved to have been a mouse in the corner for both of those discussions.