This essay was adapted from oral remarks given by Wendy Smith during a Congressional roundtable sponsored by the National Foster Youth Institute and the Congressional Caucus on Foster Youth in February. Smith is an associate dean at the University of Southern California’s School of Social Work.

KIDS & TRAUMA: FIGURING OUT WHEN TO INTERFERE

by Wendy Smith

Advocates, professionals, legislators, families, caregivers and all those who interact with the child welfare system grapple with the question of when and how resources should be invested at local, state, and national levels, to most effectively help children and families who may be touched by the foster care system.

If we are serious about helping children, we must ask ourselves with greater urgency: At what point should we begin to pay attention to families who are at risk?

The vital importance of the early years of children’s lives in setting the stage for their futures cannot be overstated.

To understand why foster care, as critical as it is in some instances, is a less effective intervention than assistance in advance of removing children from their homes, it will help to know something about stress, trauma and brain development. Some of what I will describe we know and have known for a long time, and some we didn’t really know until quite recently, but all has important implications for how we approach child welfare decisions and policies.

Some 415,000 children are in foster care in the U.S. on any given day. As a nation, we know and believe that the safety of children who are determined to be at imminent risk of neglect or physical, sexual or emotional abuse, and for whom remaining in their homes poses immediate danger, must be protected. Before that moment when a child is taken from her home and family, a great deal has already happened to all of the people in the family. And a great deal happens afterward as well.

In the past 10 years, there has been a veritable explosion of research in brain development, trauma and its long-term effects, and the importance of early attachments.

This new knowledge is crucial to the strengthening of families and the protection of children’s development and well-being. I want to highlight each of these, but first, let me share some sobering statistics:

Children in foster care are more likely than other children to exhibit high levels of behavioral and emotional problems. They are more likely to be suspended or expelled from school, to have received mental health services, and to have a limiting physical, learning or mental health condition. In one study, 60 percent of children aged two months to two years in foster care were at high risk for a developmental delay.

Things do not improve for youth who age out of care (those who graduate from foster care without being reunited with their families or adopted): While many are highly resilient, too many have fared poorly. In one study, 38 percent had emotional problems, half had used illegal drugs and a quarter were involved with the criminal justice system.

Only 48 percent had graduated high school at the time of discharge, compared with 81 percent of their peers. Only 13 percent of foster youth enroll in college (compared with 78 percent of high-income peers, and 55 percent of low-income peers), and only 2-4 percent of foster youth graduate (compared with 41 percent in the U.S.). From 41 to 60 percent of those who aged out were unemployed, and up to half had received public assistance.

Most critically, nearly 40 percent of foster youth are homeless within 18 months of discharge from foster care. As adults, those who spent long periods in multiple foster care homes were more likely to be unemployed, homeless, incarcerated, become early parents, to be dependent on financial assistance and to have chronic health conditions.

These dismal outcomes for children in our care shame us all. Why should these outcomes be so dire, and the costs to young lives, and to society, so great?

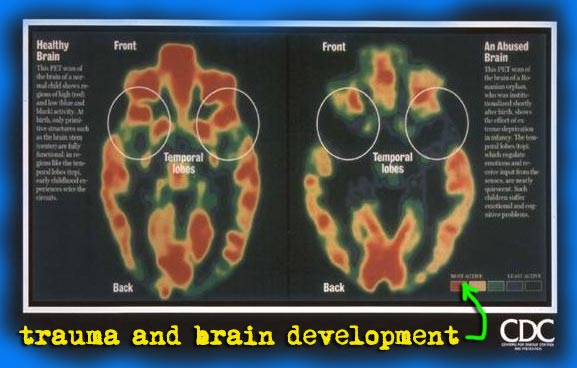

BRAIN DEVELOPMENT AND THE EFFECTS OF TOXIC STRESS

Let us consider some of what recent research on brain development, attachment, and the effects of toxic stress and trauma tells us.

Early experiences profoundly affect the development of brain architecture, the foundation for future learning, behavior and health. The architecture of the brain is constructed over time, beginning before birth and continuing into adulthood.

It becomes increasingly complex over time, with brain cells (or neurons) proliferating most rapidly during the first few years, and another period of important changes during adolescence. The majority of brain development occurs in the first five years; however, throughout life, new connections continue to occur, and connections that are not used are pruned away.

Brain development is experience dependent; our genes interact with our experiences to shape our brains. Genes provide a kind of blueprint of circuits, but experience and use determine whether certain capabilities or potentials will emerge and be firmly established or die away. Experiences of both positive and negative kinds have this shaping potential.

So, for example, exposure to certain types of stimuli–intellectual, athletic, musical–might set the stage for intellectual or athletic potentials to be realized—which is why we often see succeeding generations of exceptionally talented individuals in one family.

In the same way, for infants who are rarely spoken or sung to, language development will be negatively impacted. The occurrence of abuse or neglect during the first three years can produce changes to important parts of the brain, sometimes leading to learning difficulties, attention deficits, problems in self-regulation and self-control.

Environment and relationships play an important role: Interaction with parents or other important adults is the medium or vehicle through which the infant or young child experiences the world and him or herself.

Responsive caregiving is the key ingredient that drives optimal brain development. When caregiver responses are unreliable, inappropriate or absent, the child’s brain architecture cannot develop as expected, and this can lead to disparities in learning or behavior.

When parents’ mental health is compromised, when the need to find shelter or addiction to drugs precludes a parent from attending to a child’s needs or distress, the child is not soothed, and therefore cannot fully develop the capacity for self-soothing or self-regulation. The lack of ability to self-regulate can set the stage for all kinds of problems, including the use of substances to self-soothe.

CHILDREN’S BRAINS CAN ALSO CHANGE FOR THE BETTER

Our brains have neurobiological plasticity, giving us the capacity to change throughout life in response to new opportunities, both positive and negative. The message here is that what happens before, during, and after engagement with the child welfare system can make profound differences to the ongoing development of children and youth.

Stress, toxic stress and trauma frequently, if not always, play a part in the lives of children and families who come to the attention of child welfare systems. Stress results when demands—either physical or psychological—exceed our coping resources. It is a normal part of human existence, and an effective stress response is necessary in the face of daily challenges. It becomes a problem when stress is excessive or when it is not followed by a period of rest and recovery.

There are three basic categories of stress: positive (brief increases in heart rate and mild elevation of stress hormones); tolerable (serious, temporary stress responses, buffered by supportive relationships); and toxic (prolonged activation of stress response systems in the absence of protective relationships).

An example of toxic stress might be a homeless teen single mother with a colicky infant. These compound stressors over days or weeks, in the absence of a supportive other, might overwhelm the coping capacities of any young person; imagine if layered beneath the current difficult situation are experiences of childhood trauma.

The effects of early childhood abuse on the stress response system have been shown to continue into later life. Research suggests that many of the leading health and social problems have common origins in the enduring consequences of abuse and related negative experiences during childhood.

The ACE (adverse childhood experiences) study revealed the strong connections between trauma in childhood, cognitive and social problems, adoption of health risk behaviors, disease, disability and social problems, and, in fact, premature death.

Attachment plays an important role: The parent or caregiver mediates stress for the child. On a very basic level, think of an infant who is frightened and dysregulated by a loud noise. Ideally, a responsive adult picks up the child, providing reassuring contact and soothing, and the infant regains equilibrium.

Repeated cycles of equilibrium, disturbance and timely repair are what help us develop the ability to tolerate stress. If there is no responsive caregiver to act as a psychobiological regulator, the stress response remains in high gear, and the infant does not internalize the capacity to self-soothe. These are often the children who can’t manage themselves on the school yard, seeing threats where there aren’t any, getting into fights, or breaking down when frustrated.

Trauma is a particular version of toxic stress: high-risk events or situations in which one’s physical or psychological integrity is threatened (school shooting, gang violence, natural disaster, sudden or violent loss of loved one, physical or sexual assault). The child feels intense fear, helplessness and horror. Serious incidents of child abuse or neglect can be composed of one or more trauma events. In situations of abuse or severe neglect, the adult who is the abuser or psychologically unavailable cannot be turned to as a source of comfort, soothing and recovery.

Trauma can be acute or chronic. Chronic trauma is more likely to lead to negative developmental outcomes. Reactions to traumatic events vary based on a child’s coping responses and on the relationship between the child and perpetrator. The neurobiological response to trauma results in increased adrenaline levels and increased cortisol, the stress hormone.

COUNTERACTING THE EFFECTS OF CHRONIC ABUSE

Chronic abuse leads to overdevelopment of the stress response system (and reduced levels of pleasurable hormones), preparing a child to cope with negative environments, rather than having the expectations of a good experience with others. The child’s attention is focused on detecting threats. In the classroom, a child might experience a teacher’s criticism or correction as a threat to be defended against, or be unable to take in the lesson because he or she is caught up in worrying about a possible negative reaction from the teacher or other children. High levels of stress hormones also affect memory, and can interfere with learning in this way as well.

Foster children with histories of chronic abuse may have found themselves, in one placement after another, unable to make use of the best efforts of concerned caregivers because they have learned at the biological level to remain on alert.

What does all of this have to do with foster care? How can we best make use of what we now know about stress, trauma and attachment?

I would suggest that we can do much more to shore up families before they come to the point where children are in danger and must be removed, and that by doing so, we can substantially improve the lives of children and families at the same time that we decrease the injuries to them and the ultimate costs to society of our having to take over the role of parent for so many children.

We now know, as we didn’t before, that experience and environment have profound effects, not only on social and psychological behavior, but at the biological level. Now we know that improving the quality of experience and family environments early in a child’s life will positively affect every domain of functioning.

We all know, from having been children, or having our own, how frightening it might be when a parent is impaired or absent, or if you couldn’t go home because the rent hadn’t been paid. You might cling all the more tightly to your parent.

Many of the families of children who come into care are struggling with poverty, homelessness, health or mental health problems, addiction, or incarceration. The entry into care, while a lifesaver for some families or children, is for most a traumatic disruption of primary relationships, bringing the loss of parental figures, siblings, home, school—in short, all that is familiar or predictable.

FAMILIES AT RISK NEED HELP BEFORE CHILDREN ARE IN DANGER

So, layered atop the underlying problems, which may or may not be addressed, is a series of additional losses, stressors and problems. Families at risk can benefit from services that address these problems before children are in danger.

Our investments have typically been greater at the back end—trying to ensure that foster care is as good as it can be—and that is important, of course. But even if/when foster care is at its best, strengthening that family in advance of the extreme step of removal of a child sets the stage for more optimal development of the brain, and of the person.

When a child does not have to be occupied with managing or recovering from the trauma of maltreatment or removal, that child is much more likely to be healthy, to be able to learn and to grow into a successful member of society.

This story originally appeared in the Chronicle of Social Change