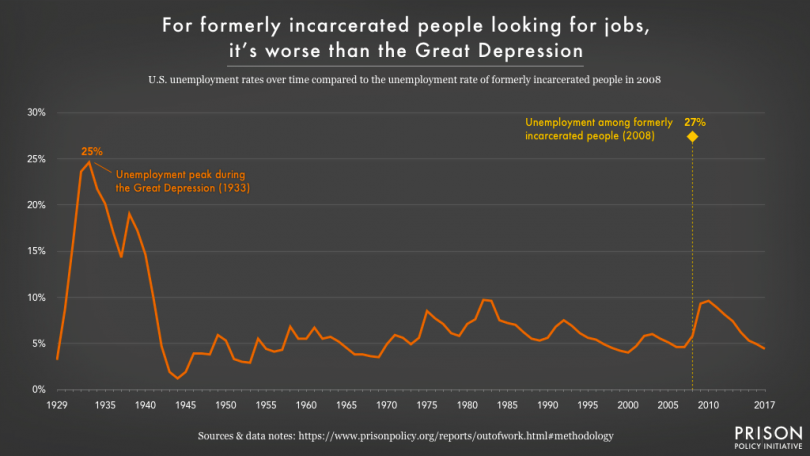

Approximately 27 percent of formerly incarcerated people are looking for a job, but are still unemployed, a rate higher even than the general U.S. unemployment rate of 24.9 percent during the Great Depression, according to a new study by the Prison Policy Initiative.

According to PPI, the statistic is the first-ever national estimate of unemployment among formerly incarcerated Americans. Researchers used data for 2008—the most recent year for which data was available—to calculate the unemployment rate. People released from prison who were between the ages of 25 and 44 had an unemployment rate (27.3 percent) that was nearly five times the unemployment rate of their general public peers (5.8 percent) in 2008.

“Unemployment among this population is a matter of public will, policy, and practice, not differences in aspirations,” according to PPI.

Researchers found that the formerly incarcerated population was more likely to be actively seeking employment than the general public. A total of 93.3 percent of formerly incarcerated are either employed or looking for work, according to the report, while 83.8 percent of their peers in the general population had or were actively seeking jobs.

“Although we have long known that labor market outcomes for people who have been to prison are poor,” says PPI, “these results point to extensive economic exclusion that would certainly be the cause of great public concern if they were mirrored in the general population.”

Every year, more than 600,000 people are released from prison, and face the formidable tasks associated with re-entering their communities, including finding work.

Research shows that employment reduces the likelihood that a person will be rearrested and returned to lockup.

Yet, people with felony records face massive barriers to stable employment.

There are thousands of legal “collateral consequences” attached to felony convictions that restrict things like voting rights, job prospects, and eligibility for government assistance, and more.

Beyond the legal collateral consequences, people with convictions on their records face stigma and discrimination.

One Northwestern University study revealed that a criminal record reduced the likelihood that a job seeker would receive a callback from a potential employer.

Not Surprisingly, Race and Gender Play a Role

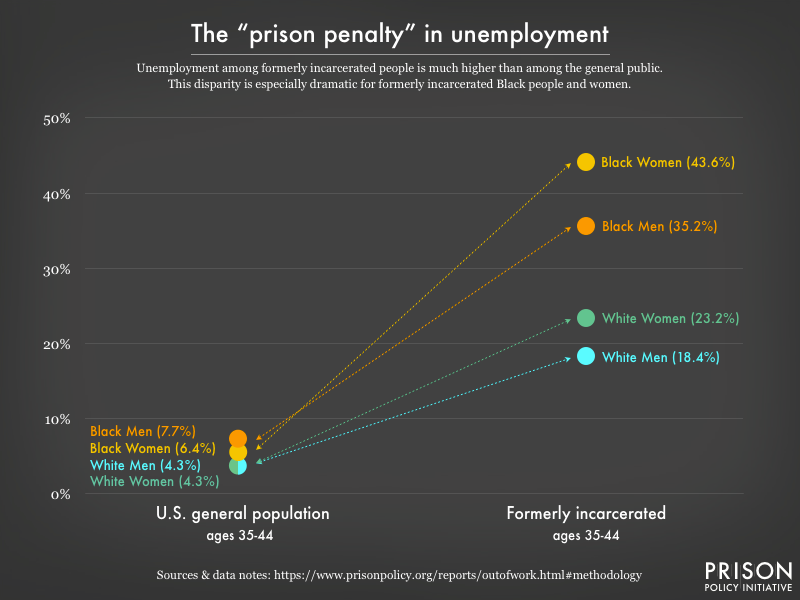

Formerly incarcerated white men have the lowest unemployment rates. Approximately 18.4 percent of white men between the ages of 35-44 with a criminal record are unemployed, compared with 4.3 percent of their peers who are not involved with the criminal justice system. White women, who had the same unemployment rate as white men in the general public, face a 23.2 percent unemployment rate if they are formerly incarcerated.

The numbers jump by double digits for black Americans. Black men have a general unemployment rate of 7.7 percent, while formerly incarcerated black men have a 35.2 percent rate of joblessness.

Black women who have been to prison are hit the hardest with unemployment, however. A general population unemployment rate of 6.4 percent for black women jumps to an incredible 43.6 percent unemployment rate for those who have been to prison.

Moreover, formerly incarcerated black women are the group most often working low-security, low-paying, and occasional jobs, while white men are most likely to have full-time jobs.

“Though Black women in the general public tend to have higher rates of full-time work than their Hispanic or white peers, low rates of full-time work among formerly incarcerated Black women illustrates that gender and race operate together in the context of reentry,” says PPI.

The Time Since Release From Prison Factor

Unemployment rates are highest in the two years immediately following release from lockup, according to the data. The numbers drop from 31.6 percent for the first two years, to 21.1 percent for people who were released between two and three years prior, to 13.6 percent for people who have been free for four or more years.

These numbers suggest that employment focused reentry services are “critical” to reducing recidivism and helping people exiting prison successfully rejoin their communities, say the researchers.

“The transition from prison back to the community is fraught with challenges; the search for employment is one of many tasks that can derail successful reentry,” PPI says. “In the period immediately following release, formerly incarcerated people are likely to struggle to find housing and attain addiction and mental health support. They also face disproportionately high rates of death due to drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide within this crucial period. Taken together, these results make it easy to understand how various barriers to reentry operate as an interconnected system to increase inequality.”

No matter how much i believe in giving a person a first chance or second chance to prove they can handle a job and become a valuable employee, i’m still going to be concerned about potential liability of hiring anyone formerly convicted and incarcerated.

The employer can face claims from customers, clients, co-workers and individuals with only random contact for torts committed by an employee in the course of his job or in connection with the job.

The employer will need to defend against those claims.

If I knowingly hired an employee with a criminal record, that is going to make it easier for the claimant to argue that i should be found liable for their damages.

If I unwittingly hired an employee with a criminal record because I’m very progressive and don’t inquire about criminal record of job applicants, then claimant can argue that should be found liable for their damages due to my negligence in vetting my new hires.