California’s controversial gang-involvement tracking database—CalGang—lacks necessary state oversight and does not adequately protect the rights of more than 150,000 people listed in the database, according to an audit of the tool and its use by State Auditor Elain M. Howle.

People who admit to law enforcement officers that they are gang members or who have gang-related tattoos are added to the database, but associating with known gang members and wearing clothing that might be gang-related also sends people into the CalGang database.

The full criteria for designating someone as a gang member on CalGang is outlined in California’s Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention Act (STEP Act), which also created sentence “enhancements” for crimes committed “for the benefit” of a gang. The outcomes can be catastrophic. These enhancements can turn a sentence of a few years into one of multiple decades, and disproportionately affect poor and minority people.

“Although CalGang is not to be used for expert opinion or employment screenings, we found at least four appellate cases referencing expert opinions based on CalGang and three agencies we surveyed confirmed they use CalGang for employment screenings,” writes Auditor Howle.

CalGang identification can also lead to inclusion in a gang injunction.

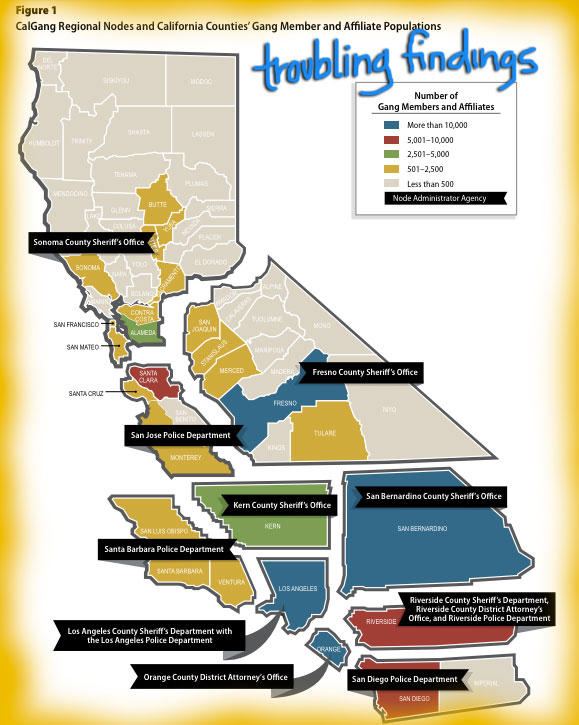

The audit looked at how four agencies—the Los Angeles Police Department, the Santa Ana Police Department, the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office, and the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office—interact with the database.

Out of the 100 individual CalGang profiles closely examined as part of the audit, the agencies could not support the inclusion of 13 of the people based on the database entry criteria.

There were also significant data errors in the profiles. For example, out of all of the CalGang entries, there were more than 40 profiles for people who were reported as being younger than one year old when entered into the database. Twenty-eight of those infant gang member entries were for people who “admitted to being gang members.”

Often, in Los Angeles and Santa Ana, gang-designated minors and their parents were not properly notified and given a chance to contest an entry into CalGang. In 2013, CA Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill requiring both notification and an opportunity to fight a juvenile’s designation.

Another long-reported issue is that once a person is in CalGang, it’s extremely difficult to get off the list. In fact, more than 600 people listed in CalGang are scheduled to be taken out of the database at a date beyond the purge date of five years for profiles that haven’t been updated. Many of those 600 are not scheduled to be dropped from the database for more than 100 years.

And the CalGang Executive Board and the California Gang Node Advisory Committee operate without transparency, legal authority, or public engagement.

The “weak leadership structure has been ineffective at ensuring that the information the user agencies enter is accurate and appropriate, thus lessening CalGang’s effectiveness as a tool for fighting gang-related crimes,” the audit says.

Peter Bibring, director of police practices for the ACLU of California says the audit backs up knowledge community members have had all along, namely that “CalGang is an ineffective tool full of inaccuracies that results in violations of people’s rights.” The inadequate oversight and faulty system “have a real impact on people’s lives when law enforcement relies on such a flawed system for judgments about prosecutions, employment and even deportation,” Bibring said.

The audit recommends putting the California Department of Justice in charge of overseeing and regulating use of the database, publishing yearly statistical reports, and standardizing and enforcing training for CalGang users. Law enforcement users would then implement review procedures and report results back to the CA DOJ. The state auditor also says a technical advisory committee should be established to make recommendations to the Justice Department regarding policies and procedures, and to obtain input from the public.