Editor’s Note:

A growing body of research in the realm of neuroscience shows that young adulthood—meaning between the ages of 18 and 24—is a distinct period of development, with significant cognitive changes occurring into the mid-20s.

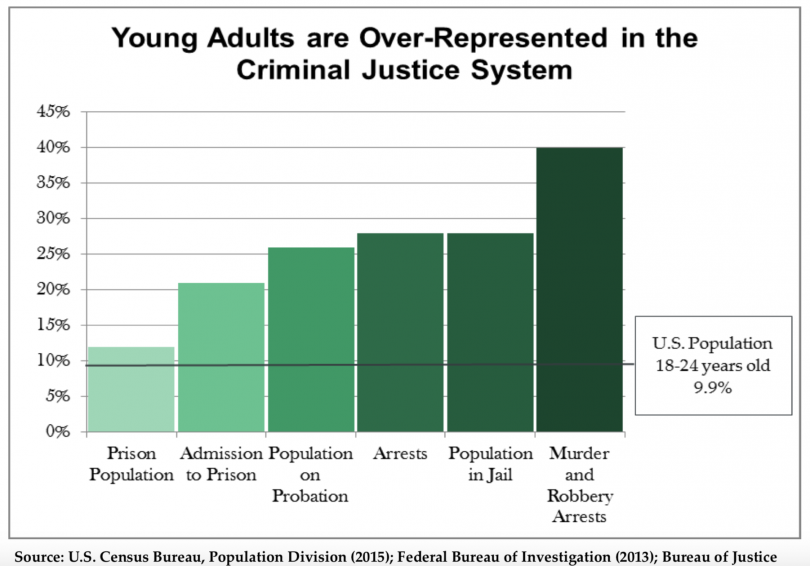

In the criminal justice realm, the “young adult” age group is disproportionately likely to commit crimes, including violent crimes, and to reoffend, which makes the research, and the issue, of particular relevance both to public safety, justice reform—and to state budgets.

(In Massachusetts justice experts unhappily reported that the state “currently spends the most money on young adults in the justice system but gets the worst outcomes.”)

In response to this enhanced understanding of young adults’ development, a growing number of jurisdictions have explored strategies to use resources more efficiently to improve outcomes for young adults in both the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems.

One example is the California Department of Corrections’ Youth Offender Program (YOP), which delegates a special classification committee to review cases of young adults transferring to the adult system. Based on the youth’s merits, the committee may place the young inmate in a lower-security prison yard, with a wider variety of programs and classes. The goal is to keep youth away from “more serious and violent criminal influences, found at high-security level prisons, and to better prepare these same young people to succeed when they are released. Some of the newer YOP programs even provide mentors for the young inmates.

These same issues got San Francisco DA George Gascon, together with then SF probation chief, Wendy Still, to launch a Young Adult Court (YAC) for eligible young adults, ages 18 to 24. The YAC, which came into being in 2015, and was the first program of its kind in the nation, is a hybrid of the adult and juvenile court systems, but specifically designed to “align opportunities for accountability and transformation with the unique needs and developmental stage of this age group,” according to the court’s website.

Now there are such courts in Brooklyn, Chicago, Idaho, Nebraska and other areas.

Meanwhile, European nations such as Germany, the Netherlands, Croatia are exploring their own models of specialized justice for young adults, or “emerging adults” as some call the 18 to 25 (give or take) age group.

Curious about what the Europeans were doing, in March 2018, the Emerging Adult Project at the Columbia University Justice Lab organized an educational trip around Europe to explore some of these emerging models. The director of the Emerging Adult Project, Lael Chester, and the co-director of the Justice Lab, Vincent Schiraldi, had meetings with officials in the Netherlands and Croatia in the first part of this trip, and then went to Germany with a Massachusetts delegation.

The report below by Vincent Schiraldi, which first appeared in The Crime Report, is the first of several accounts of what he and the group learned.

Raising Age to 23? It Works for the Dutch

by Vincent Schiraldi

Can The Netherlands teach Americans anything about how to address young, court-involved adults?

My colleague Lael Chester, Director of the Columbia University Justice Lab’s Emerging Adult Project, and I recently spent two days in Rotterdam and The Hague touring the Dutch justice system as part of our exploration of how Croatia, Germany, and the Netherlands work with young adults who become involved in the justice system.

We focused on the Netherlands’ approach to sentencing young people up to age 23 under juvenile law and, on the rare occasions they are incarcerated, confining them in juvenile facilities.

The Netherlands has had a separate juvenile code and judiciary for juveniles since the beginning of the 20th Century, and has debated special treatment for young adults since the 1950s.

In 2011, conservative Dutch State Secretary of Security and Justice Fred Teeven proposed to raise the age at which emerging adults could be treated as juveniles.

After several years of debate, the Adolescent Criminal Law passed in 2014, allowing youths whose crimes occurred prior to their 23rd birthday to be included in the juvenile system. Ironically, this wasn’t much of a legal change: it has been possible to sentence youth up to age 21 under Dutch juvenile law since 1965, but in practice this provision was rarely used.

Vincent Schiraldi, Senior Research Scientist. Columbia University School of Social Work/ courtesy of Columbia University

Due to a quirk in adult vs. juvenile court funding, cases of youth over age 18 originate in adult, rather than juvenile court, which has limited the impact of the law. Some of those we interviewed seemed to consider the opportunity to sentence emerging adults under juvenile law as being limited to youth who demonstrated special immaturity, often through borderline IQ levels; to “juvenile” type offenses behavior; and to other indicators of immaturity like living with one’s parents, still being in school, and not yet attaining stable employment.

Dutch emerging adults are specially evaluated by probation and forensic psychologists who recommend whether they should be handled under adult or juvenile law. These evaluations were especially valued by several interviewees.

A range of “educational” options are available for young adults including specialized probation caseloads and rehabilitative programming. And, as mentioned above, if they are treated under juvenile law, they may be incarcerated in juvenile facilities.

A change in state vs. local funding for juvenile programs was enacted in 2015, which may be limiting the impact of the law by making accessibility of programs for juveniles, as one interviewee put it, “a pain in the ass.”

Several of those interviewed agreed, if more gently.

During our tour we interviewed a professor from Erasmus University Rotterdam’s School of Law who is also a part time judge (Jolande uit Beijerse); a full time juvenile judge (Lian Pit); a Rotterdam-area probation official (Ruben Laats); a prosecutor (Rolan van Dongen); a juvenile correctional administrator (Marijke van Genabeek); a defense attorney (Luns Van der Velden) and a group of researchers led by Andre van der Laan, PhD, from the Ministry of Security and Justice.

We toured a youth correctional facility in which young people could be confined for crimes they committed up to age 23. We also had the opportunity to sit in on the trial of an emerging adult and to chat with him before sentencing.

It’s still early, so there’s not much data on outcomes (but thankfully, van der Laan and his colleagues are conducting quasi-experimental research on the Adolescent Criminal Law’s impact).

Although only .9 percent of those 18 through 20 were tried under juvenile law prior to 2014, that percentage has steadily risen to 7.3 percent by 2016. Meanwhile, 1.1 percent of those 21-23 were sentenced as juveniles in 2016.

Dutch youth age 16 and 17 can be tried in adult court for more serious offenses, but that rarely happens.

An argument against raising the age beyond 18 in the U.S. is that crossing that line might make it easier for policymakers to cross the line the other way and try more juveniles as adults.

A counter-argument is that the presence of older youth in juvenile court may promote more leniency for 16 and 17-year-olds who were formerly considered older and more serious in juvenile court.

Early results in the Netherlands—and they are early—seem to support the latter argument. Two-tenths of a percent of 16 and 17-year-olds were prosecuted as adults in 2016, down from 2.1 percent in 2014, a 90 percent decline in two years.

Put another way, in 2014, 3.1 percent of 18- to 23-year-olds in the Netherlands were tried as juveniles, while 2.1 percent of 16 and 17-year-olds were tried as adults. By 2016, only .2 percent of 16 and 17-year-olds were tried as adults while 4.7 percent of 18 to 23-year-olds were tried as juveniles.

The Dutch we interviewed were divided as to whether a system that more resembled the German system (where cases of emerging adults up to age 21 originate in juvenile court and two-thirds stay there) is better. Some felt more young adults should be treated in juvenile court; others were comfortable with such treatment being exceptional, while still others were waiting for the evidence to come in.

We’ll be paying close attention.

One final point…

There are about 400 youth incarcerated in public or private, non-profit facilities in the Netherlands, a nation of about 17 million people. That number is dwarfed by the 53,000 youth incarcerated in the U.S., a nation of 326 million.

The number of Dutch juvenile institutions has decreased dramatically from 15 facilities with 2,600 beds in 2007, to only five with 500 beds in 2016, despite adding the possibility of sentencing youth up to age 23 as juveniles.

Juvenile institutions are now under review nationwide, with the intention to switch to a customized system of local, small-scale facilities located near the youths’ own social network, combined with a few national facilities with specialized care and higher security.

A small-scale pilot was launched in Amsterdam in 2016 providing places for youth who attend school and/or work during the day and return to the shelter in the evening and on weekends.

(Lael and I, along with Harvard Kennedy School student Sibella Mathews, will be publishing a more formal article on thE Netherlands, and the other two countries we’re visiting later this year).

I’ll write more from our next stop, Croatia, soon…

Vincent Schiraldi is senior research scientist at the Columbia University Justice Lab. He has served as New York City Probation Commissioner and director of juvenile corrections for Washington, DC. An earlier blog describing his European trip can be accessed here.

This story first appeared in the Crime Report.

Why do the people who occupy the top rungs of the social justice racket ( Schiraldi) always point to the whiter than white countries of Scandinavia and Northern Europe as examples of socialist engineering? Isn’t that like white privilege or something? Instead of looking to the decrepit and rotting countries of old Europe why not look to places like Singapore for ideas on dealing with juvenile crime?