By Jane Ellen Stevens

The overwhelming majority of the 2.3 million people in U.S. prisons have experienced significant childhood trauma.

Now a man who teaches the construction trade to prisoners believes he can, at the same time, teach those men to get to know their trauma, find resilience, and thereby change their lives.

Over the last 20 years, intense research has revealed that people who have a lot of childhood adversity have seven times the risk of becoming an alcoholic, 12 times the risk of attempted suicide, twice the risk of cancer and heart attacks. They’re more violent, more likely to be victims of violence, have more broken bones, more marriages, and use prescription drugs more often than people who have no childhood adversity. They are also more likely to end up in jail or prison.

A big surprise in the groundbreaking Center for Disease Control-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study [known as the ACE Study] — in addition to learning that most of us have at least one ACE — was how “normal” and ordinary some of the types of adversity are. Seeing your parents divorce. Living with a family member who’s alcoholic or depressed, or suffers from other mental illnesses. Experiencing verbal abuse, which includes being screamed at every day as well as being quietly told by your mother, “I wish you’d never been born.”

Then there’s the stuff that you expect will mess with your head — physical and sexual abuse. Physical neglect. Emotional neglect — hardly being acknowledged or talked to during your entire childhood. Watching your mother being hit. Having a family member in prison.

Since the ACE Study was published, dozens of other ACE surveys showed similar results. Recognizing that definitely more than 10 types of ACEs exist, other surveys have included racism, bullying, witnessing violence outside the home, serious illness or accident in the family, experiencing war, losing a family member to deportation, ending up in foster care, etc.

All these experiences damage the function and structure of kids’ brains. Kids experiencing trauma act out. They can’t focus. They can’t sit still. Or they withdraw. Fight, flight or freeze – that’s a normal and expected response to trauma. Kids who are experiencing trauma live in survival mode. They frequently have a hard time shifting their attention from the survival brain to the learning brain. Their schools often respond by suspending or expelling them, which further traumatizes them.

When they get older, they cope by drinking, overeating, doing drugs, smoking, as well as over-achieving or engaging in thrill sports. Without intervention, these coping behaviors may continue throughout their adult lives. To those suffering from trauma, these are solutions. They’re not problems. Nicotine reduces anxiety. Food soothes. Some drugs, such as meth, are anti-depressants (and used to be prescribed as such).

Addressing trauma in lock-up

Most prisons in the U.S. don’t understand or address ACEs and toxic stress. The few prisons that do, however, see some pretty remarkable changes.

The Washington State Penitentiary, located in Walla Walla, is one of those few. There Tony McGuire talks to the inmates in his construction trades apprenticeship preparation class (CTAP) about ACEs, trauma, and resilience every single day.

Not only is McGuire teaching the guys a trade, he also teaches his class members how to be healthy, happy and well-adjusted employees.

But becoming a healthy, happy, well-adjusted employee, it turns out, is far harder than learning basic carpentry, plumbing, electrical and HVAC—heating, ventilation, air conditioning.

McGuire, who is paid by Walla Walla Community College to teach the course, treats the 12 to 16 members of each class, which he teaches four times a year, as if they are workers on a job site. Over the 14 weeks of the class, the inmates, all from the medium-security part of the prison, split into four teams to build four 8-foot by 8-foot houses. They learn professionalism at the same time as they’re learning how to install a plumbing system.

But because the inmate/students all have high ACEs scores and live in prison, at the beginning of the course, their tolerance for the emotional stress of learning something new can be very low.

To get their attention — and a dose of what will happen to them in the outside world if they lose it on the job — McGuire says (never yells), “You’re fired.”

“When these guys are living so close to the breaking point all the time, they are functioning in survival mode,” he explains. He’s teaching them to “problem-solve and do work confidently in a way that makes them employable.”

Learning to respond not react

At the beginning of the course, McGuire explains ACEs science to his students in order to help them understand the ways their brains get twisted into survival mode, and why they’ve been stuck in that mode for most of their lives.

But he teaches these lessons from a perspective of resilience. His message is, yeah, these things that happened to you when you were young were awful, truly awful. Nothing a kid should have to endure.

But, guess what? You weren’t born bad. You had no control over what happened to you when you were a kid…no control. And, best of all, you can change.

This is news to those serving prison time. Being over-reactive or getting triggered into rage has been such an ingrained way of life for many of the guys in the class that they don’t even know there’s another way to live. With each blowup, with each meltdown, McGuire reminds them: “Respond. Don’t react.”

To develop the brain muscles to do that, they learn about ACEs science: the ACE Study, how toxic stress from experiences those ACEs eats away at the brain and the body and the spirit, how it’s passed on from parent to child (epigenetics), and how practicing resilience can actually heal your brain and body to start to make you whole again.

To give his students an idea of some of the ACEs that they’ve experienced, McGuire has them take the ACE survey.

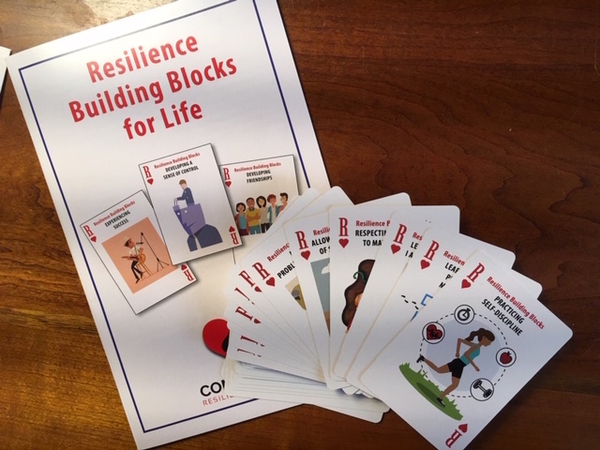

[You can take the simple ten question survey yourself here.]McGuire also provides a booklet, “Resilience Building Blocks for Life”, published by the Community Resilience Initiative (CRI) in Walla Walla, WA, one of the pioneering communities in the worldwide ACEs movement. The booklet reviews ACEs and brain science, including how to figure out what brain state you’re in. Are you deep in the brain stem, in survival mode and just barely hanging on? CRI also produces a deck of 42 “Resilience Trumps ACEs” cards. Each card features one resilience building block: Developing a Sense of Control. Developing Positive Relationships. Giving Back to the Community.

McGuire provides a booklet, “Resilience Building Blocks for Life”, published by the Community Resilience Initiative

After learning the basics in the first classes, students spend five minutes of each teaching day discussing one card with McGuire. Since the prison doesn’t allow decks of cards, McGuire obtained permission to copy the resilience cards onto sheets of paper that inmates can tape to the walls of their cells.

McGuire helps his trainees understand that when we make sense of how our brains work, we’re better equipped to respond, not react.

He’s put together a small library for class participants. The books include Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman (“This really spoke to me,” says McGuire. “How can you manage when you wear your heart on your sleeve?”). Becky Bailey’s Easy to Love, Difficult to Discipline, “for dads in the class who discipline out of anger.” When the class participants look at the cover of Bailey’s Managing Emotional Mayhem: The Five Steps for Self-Regulation, “they think it looks childish, but it’s really practical, and, after they read it, they think so, too.” Driven to Distraction, by Edward Hallowell and John Ratey — “It’s an ADD-ADHD book. I’m a high-functioning ADD person, and I’m sure these guys could use it, too.” Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score — “how the body integrates past trauma.”

McGuire’s own ACEs

The first time McGuire learned about ACEs was in Fall 2016, in a seminar organized by Teri Barila, co-founder of CRI. When he filled out the ACE questionnaire, he counted up his ACE score. It was 8. “Oh, this is interesting,” he thought. It explained a lot of his childhood and his actions growing up.

But McGuire was also really fortunate to have had extremely strong resilience factors in his life in addition to the ACEs.

For instance, there was abuse in his family and his father left when he was four years old. But after his father left, his mom moved, and things improved.

“Our neighbors were like my surrogate parents,” he says. “They really helped my mom and me. My best friend’s dad included me in sporting events and family outings. That was very pivotal for me. I was also the baby, and my mother treated me a lot differently after my dad was gone. I didn’t experience as much abuse as my siblings.”

He also developed close friendships with 15 high school classmates. Most of them still live in Walla Walla. “All of us are still close,” says McGuire. “We’re raising our kids together.”

Despite all his ACEs, these resilience factors enabled McGuire to have a successful 16-year career as a contractor before joining Walla Walla Community College to teach the CTAP course. He also has solid marriage of 22 years, and two kids who are steeped in ACEs science thanks to their father.

ACEs go to prison and beyond

After he learned about ACEs science, McGuire immediately incorporated it into his building course. Over the last five years, 236 people have completed the class. About 110 of those who participated in the course since 2016 have learned about ACEs science.

Now, McGuire wants to start gathering data on how participating in the course has affected his students’ recidivism.

McGuire has also become a champion for spreading this knowledge. Over the last 16 months, he’s given 40 presentations about ACEs science—for students at the community college, members of the state board of community-technical colleges, and for the directors of all the housing authorities in Washington state.

Within the prison, ACEs science, including resilience, is getting traction outside McGuire’s class. He hears reports of fathers telling their wives and children about resilience factors in phone conversations. Inmates form small groups to read and discuss books and resilience factors. A former inmate makes a point of letting him know how the course had changed his life.

And now the superintendent of the prison and other upper-level managers have shown interest.

When he first started integrating ACEs science into his class, McGuire says inmates hadn’t heard anything about it before they signed up for the class. “Now they’re asking about it right when they come in the door,” he says.

And when McGuire had a speaking engagement near the town of the mother of one of his inmate students, she came to see him to thank him for the work he’s done with the man, a 35-year-old serving a ten-year sentence.

“You’ll never know the effect you’ve had on my son,” she told McGuire. “When we talk, he has made me proud.”

Author Jane Ellen Stevens is the editor of ACES Too High, where a version of this story first appeared.

If you’re interested in learning more about and participating in how people, organizations, systems, and communities are integrating ACEs science, consider joining Stevens’ companion social network, ACEs Connection,

For any planning to be in the state of Washington in June, Tony McGuire is speaking about his work at the 4th Annual Beyond Paper Tigers Conference in Pascoe, Wash., as part of the “Big Ideas” series, in the Big Room, from 12:30-2:00 pm, June 27, 2019.

Beautifully written, well researched and a gem in the body of work about ACEs. These are exciting times as we learn how our childhoods physiologically change us as adults. There are ways to heal – I have an ACE of 10 and am happy, healthy and whole today – due in large part to people like you spreading the information. Tony is an inspiration. Thank you

If you would like to grow your know-how only keep visiting

this website and be updated with the most up-to-date information posted here.