Update: As of May 6, 2020, none of the kids in LA County’s juvenile probation camps and halls had tested positive for COVID-19. A total of 49 kids have been tested. Twenty-eight youth are under medical observation as they await the results of coronavirus tests taken upon their arrival into lockup. Three other kids are under medical observation with COVID-19 symptoms. Two of those kids are detained at Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall, where 7 staff members have tested positive for the virus. Two other staff members at the Dorothy Kirby Center have tested positive, but had been on long-term leave from work before contracting coronavirus.

At the national level, 229 kids and 398 staff in juvenile lockups had tested positive for COVID-19, as of May 6.

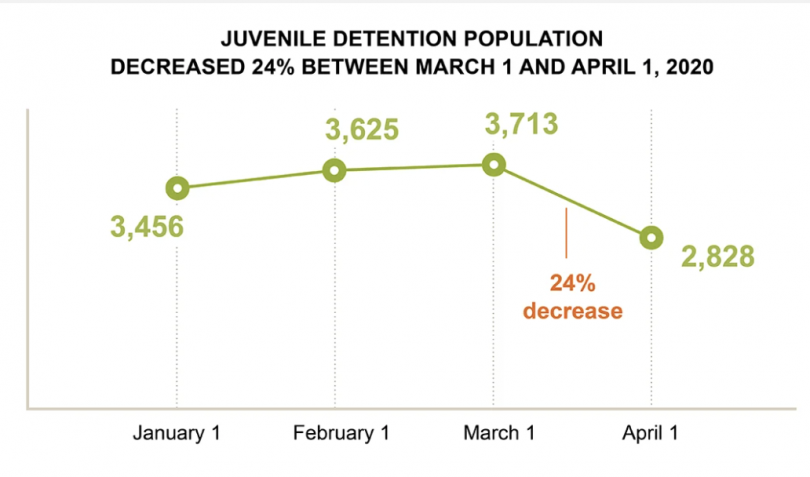

A survey of juvenile justice agencies in 30 states showed a 24 percent decrease in the local juvenile detention population — from 3,713 to 2,828, between March 1 and April 1, 2020, as the pandemic came into focus and government leaders took action to slow the virus’s spread.

The survey, conducted by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, along with the Pretrial Justice Institute and Empact Solutions, found that the population reduction could mostly be attributed to a 29 percent drop in daily admissions. The rate at which kids were released from incarceration was less impacted, but still experienced moderate changes. In January, 59 percent of incarcerated youth included in the survey were released. In February, the rate dropped to 56 percent, before increasing by 11 percent to land at 62 percent of kids gaining release from incarceration.

More than 48,000 justice-involved kids were held in facilities away from home on any given day in 2017, according to Prison Policy Initiative’s “Whole Pie” analysis of youth confinement in the U.S., released in December 2019.

The vast majority of these confined kids are in locked correctional facilities, including juvenile detention centers, long-term secure facilities, and adult prisons and jails.

The Annie E. Casey survey does not include state lockups or adult facilities, and featured a relatively small sample of the total national population of locked up kids. Still, it offers signs that the coronavirus crisis has triggered a shift in the juvenile justice system.

This year, it took these jurisdictions in 30 states a month to drop the youth detention population by 24 percent, a feat that took the nation seven years (2010-2017) to complete, according to the foundation.

“We are hoping this crisis teaches us that jurisdictions can safely reduce detention even more dramatically than many already have and keep young people who have been in trouble with the law safely in their communities,” says Lisa Hamilton, the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s president and CEO.

Still, far more can be done to protect vulnerable kids in carceral settings nationwide, advocates say.

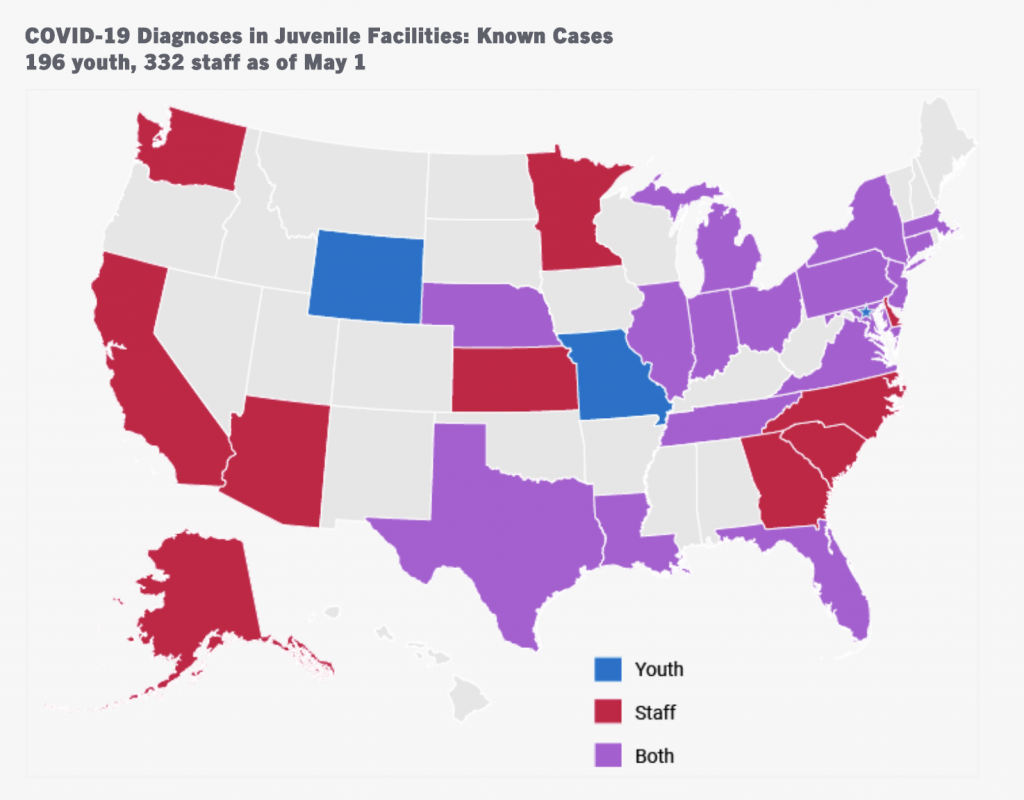

As of May 1, 196 kids and 332 staff members had tested positive for COVID-19 in juvenile lockups across the nation, according to an ongoing analysis by The Sentencing Project.

Image by The Sentencing Project

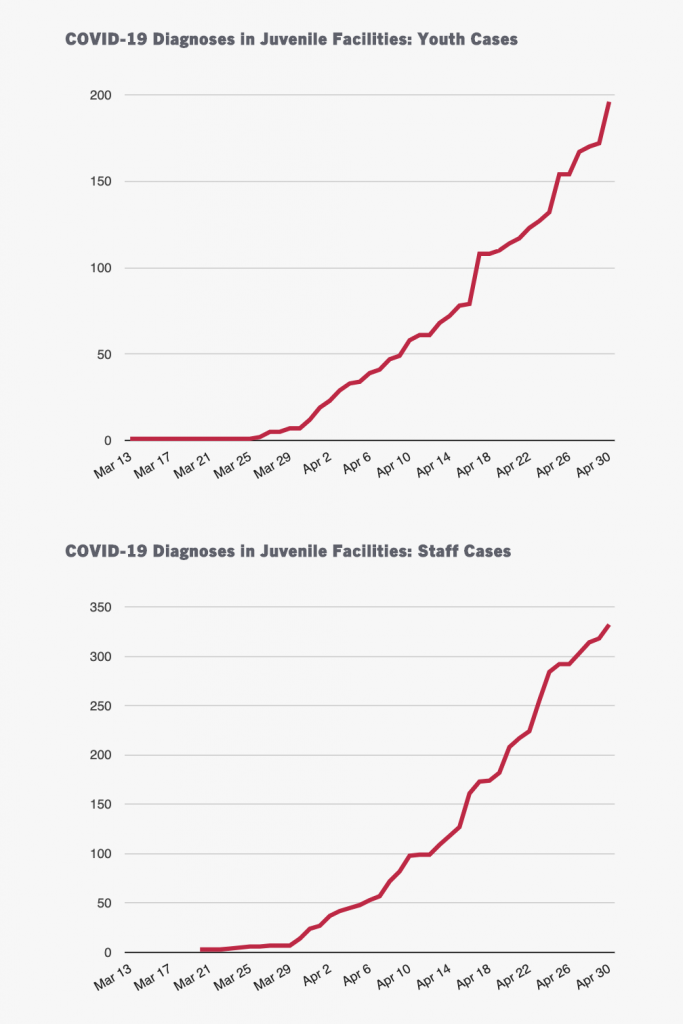

From April 1 to April 30, the number of kids in lockup with COVID-19 exploded from 19 cases to 196. During the same period staff numbers multiplied twelve-fold from 27 to 332. The number of diagnoses has not leveled off, but continues to climb. State and local officials must respond by releasing more kids from the virus-vulnerable setting of juvenile lockup, criminal justice experts say.

Approximately 70 percent of incarcerated minors are locked up on non-violent charges, according to The Sentencing Project. Even under normal circumstances, “their incarceration is often unnecessary and counterproductive.” Many more young people could be safely released to their families and to community-based services.

Graphs by The Sentencing Project

Cases in California

As of May 3, three staff members in California Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) facilities reported that they had tested positive for coronavirus.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation says that no youth in state custody has tested positive for the virus, so far. And it’s not clear how much testing the state has done inside its four DJJ facilities. The CDCR’s patient testing tracker, does not include testing or case information for the youth lockups, including the two adjacent facilities — N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility and OH Close Youth Correctional Facility — that have positive employee cases.

At the local level, in mid-April, Loyola Law School’s Center for Juvenile Law and Policy and the Independent Juvenile Defender Office of the LA County Bar Association petitioned the California Supreme Court to take action to push LA County’s foot-dragging juvenile courts to release more kids from the county’s youth lockups and send them back home.

The courts have thus far refused to consider releasing certain categories of youth in custody (something that LA Sheriff Alex Villanueva has done to thin the adult population), but instead, insist on reviewing every youth on a case-by-case basis. All the while, the courts are forced to operate in a diminished capacity, and coronavirus cases in juvenile facilities continue their swift upward trajectory.

So far, none of the 17 kids tested for coronavirus in LA County’s lockups have tested positive for the virus, but 9 staff members at Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall have tested positive.

In an interview with Liz Fiore for PEN America’s Works of Justice Podcast, Vincent Schiraldi, Co-Director of the Columbia Justice Lab and a senior research scientist at Columbia School of Social Work, said criminal justice leaders must release far more kids than have been released, so far.

“Step one, is get big numbers out,” said Schiraldi, who also formerly served as director of Juvenile Corrections in Washington D.C. and Commissioner of New York City Probation. “Get them out of your facility — right now — in big numbers. Don’t do a bunch of individualized blah blah blah, which is what everybody always wants to do.”

“Yes, we get it,” Schiraldi continued. “Some of the kids will be, in your view, too dangerous to release.” But there are thousands more low-risk kids that can still be sent home. In addition to releasing these youth, officials must “take a very careful look at anybody who’s left … especially anybody that has asthma … or any other medically vulnerable kids.”

“We should be looking at this moment, not just as an opportunity to keep kids safe, but as an opportunity to improve” areas of the system that have long needed fixing, said Schiraldi.

Juvenile detention “is a disaster right now,” he said. “Everybody is really concerned about putting a kid into that disaster.”

“We should have always been concerned about putting that kid into that disaster,” said Schiraldi. “Not just now because they might get COVID-19, but always, because they might get beaten up, they might get raped, their chances of success upon release go down, and because it’s dramatically racially and ethnically disparate. Those should have been our concerns every single day.”

While we sit and wish for life to go back to normal, there are some facets of life that should not go back to “normal.”

“Mass incarceration is one of them,” Schiraldi said. “We don’t want to fill these facilities back up. We don’t want to get back to that normal.”

What are the numbers for LA Probation facilities