As most readers know, local prosecutors have a staggering amount of discretion when it comes to deciding whether to use the many legal tools they possess to move the prosecutorial dial toward much harsher sentences and other legal consequences, or in a more justice-reform-minded direction.

According to a study that we reported on earlier this summer, although for more than a decade, Americans have moving in the direction of justice reform , the majority of local prosecutors still tend to use their direction in a law-and-order direction.

More recently, of course, there has been a new breed of progressive district attorneys — like George Gascón in Los Angeles, Chesa Boudin in San Francisco, Philadelphia County’s Larry Krasner who was reelected earlier this year to a second term, and a growing list of others.

This expanding group won over voters to a great degree by promising to use the enormous authority vested in their respective offices to undue the damage done by the lock ’em up fever of previous decades, to move the prosecutorial dial in the direction of reform.

This same group is taking grief for their new direction. Such is the case of George Gascón, who is up against recall efforts from conservative-leaning prosecutors and other law-and-order advocates, and cable TV hosts.

Yet, while there are varying opinions about decisions individual prosecutors make, there has been virtually nothing in the way of empirical research to examine the larger and more complex national picture of how and why individual prosecutors exercise their their discretionary power.

Until now.

In a newly published study, law professor/researchers Megan Wright, Shima Baradaran Baughman and Christopher Robertson, — who are respectively from Penn State, University of Utah, and Boston University — have attempted to probe that particular mystery.

Power that is unparalleled and nearly unchecked

“In their charging and bargaining decisions,”write the authors, “prosecutors have unparalleled and nearly-unchecked discretion that leads to incarceration or freedom for millions of Americans each year.

Prosecutors, wrote the three authors, have more discretion than “courts, legislators, or any other justice system player, in the aggregate, prosecutors’ choices are the key drivers of outcomes.”

These outcomes local prosecutors are driving with the fruits of their discretion include, “rates of mass incarceration or the degree of racial disparities in justice.”

Yet, never mind the sky high stakes, no one has looked at how and why prosecutors make their decisions.

“We do not know whether they consistently charge like cases alike or whether crime is in the eye of the beholder,” the authors write. And if the latter, what variable does said “beholder” use to make up his or her mind?

The researchers also wanted to know what kind of limits, supervision, or particular guidelines prosecutors work within.

“What kind of information do prosecutors rely upon, when making their decisions?” they wanted to know.

Prosecutors’ decisions have been called a “black box” for their inscrutability, wrote the authors.

It was time, they said, to break that “black box” open.

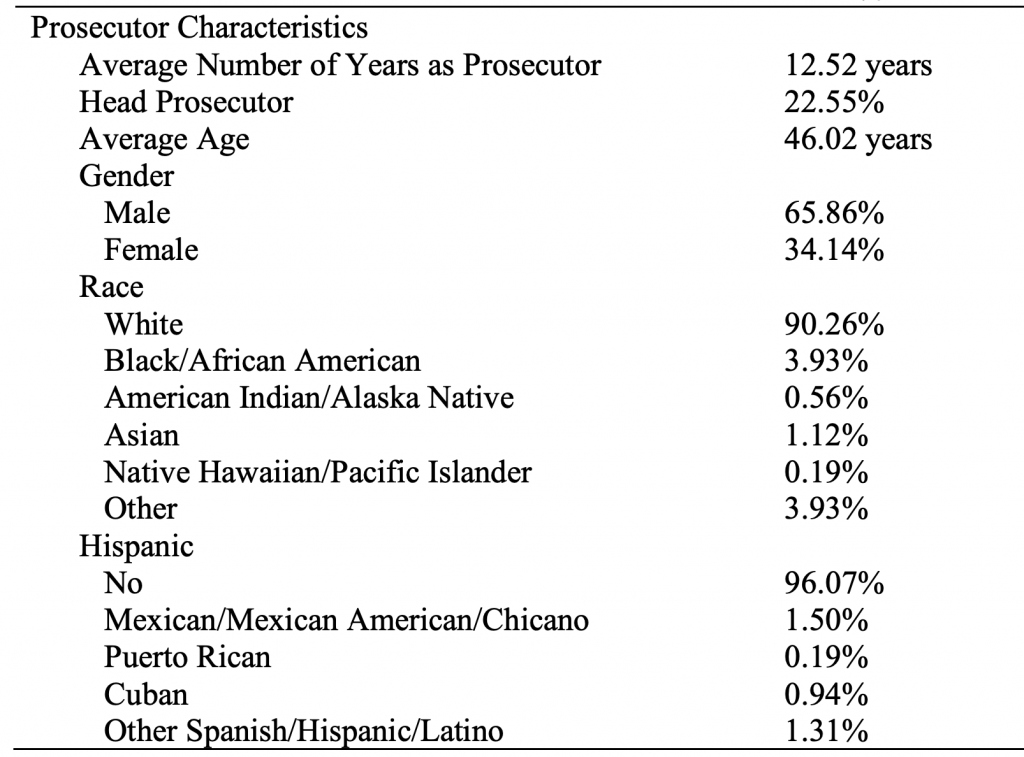

And so they did. Wright, Baughman, and Robertson and their teams recruited 542 prosecutors nationwide, and had them charge a single identical case. They were to specify the plea bargain terms that they would seek, the sentences they would ask for, and then explain how they made their decisions.

The researcher/authors also asked their 500 plus prosecutorial respondents about their internal office guidelines and procedures, along with other information and/or external boundaries they rely upon when making charging and bargaining decisions.

(By the way, in case you’re curious, Wright, Baughman, and Robertson are respectively an Assistant Professor of Law, Medicine, and Sociology, Penn State Law and Penn State College of Medicine, an Associate Dean of Faculty Research and Development, Presidential Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Utah College of Law, and N. Neal Pike Scholar and Professor of Law, Boston University School of Law.)

Since there was no “field experimental evidence” comparing how prosecutors across the U.S. charge cases that have similar facts, Wright, Baughman, and Robertson figured they could provide “the next best thing,” namely insight into how prosecutors wish they could charge a case, what limits their charging, what guidelines they are required to follow, and what exactly prosecutors say they consider when they charging a particular case.

As their experimental case, the author/researchers asked each of their 542 prosecutors to read two fictional police reports about a relatively minor crime. And then the prosecutors were to describe what charge or charges they would bring, a choice that included the option of no charges at all.

In the research vignette, a man at a train station was arrested for, in the words of one arresting officer, “yelling obscenities, stopping patrons for money, and brandishing a knife.” The man was emotionally distressed from a recent break up with his girlfriend and needed money for a train ride, but when no one gave him any money, he became more upset. One witness reported that the man, while holding a knife, had grabbed a woman’s arm after she refused to give him money, but did not hurt or threaten her. Although people at the train station were scared, no one was physically hurt. The man submitted to an arrest without incident.

Minor crime, wide variety of prosecutorial responses

The researchers also provided their participating prosecutors sample criminal statutes and sentencing guidelines and asked prosecutors what monetary penalty or term of confinement, or both, they would recommend, if any, and the reasoning for their recommendation.

“These were open-ended questions,” said the researchers, adding that space was provided for respondents to write at more length their penalty recommendations and their reasoning for those recommendations.

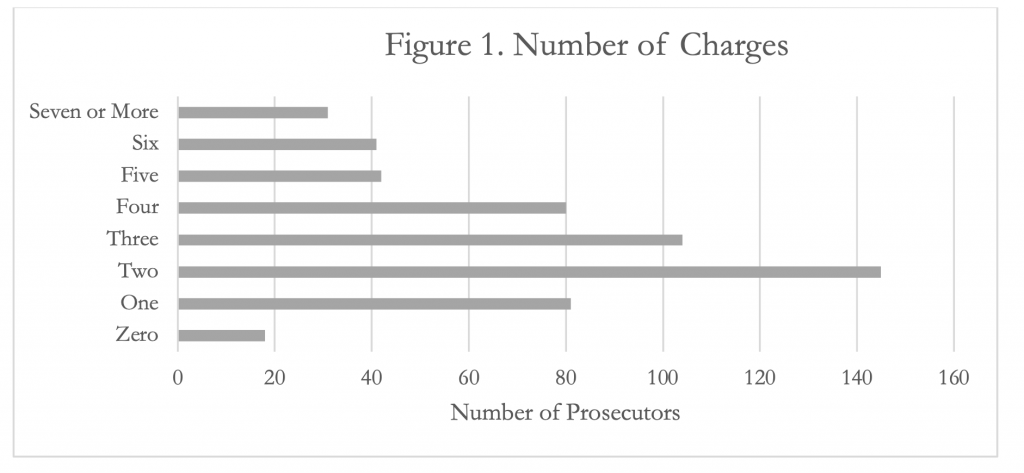

“We found extremely wide heterogeneity in how respondents resolved the exact same case. Although 18 respondents resolved the case without pressing any charges, the most common response was to impose two charges.”

Yet, some prosecutors sought seven or more charges.

Similarly, although many of the prosecutor/respondents asked for no monetary penalty at all, and many sought a monetary penalty of $500 or less, some demanded of the created suspect as much as $5,000.

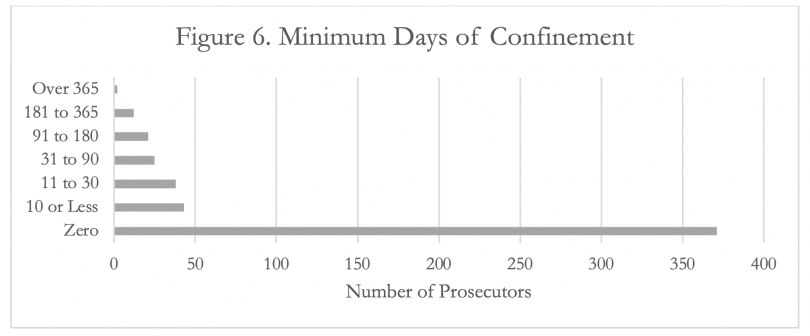

Most strikingly,” they wrote, “we saw many respondents resolving the case without any jail time, but many others demandeda month, and some wanted the man to be sentenced to lock-up for up to two years.

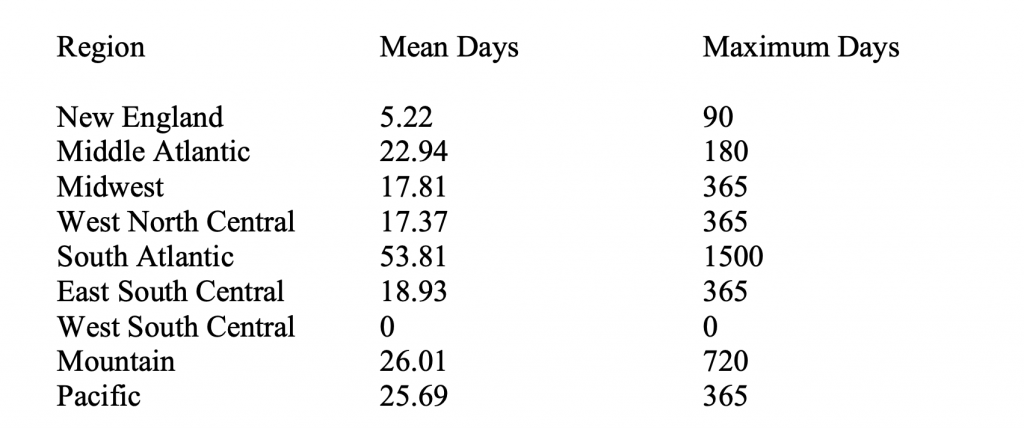

Interestingly, Wright, Baughman, and Robertson also were interested to see there was “significant variability” in the number of charges and recommended punishment from region to region.

So what does this all mean?

For one thing, wrote the three authors, the wide variability in prosecutorial decisions, they said, was consistent with a lack of meaningful supervision or guidance that many of the prosecutor-respondents used during charging.

“In our survey,” the authors wrote, “nearly three-quarters of prosecutors reported that they decided alone; their supervisors provided no direction into the initial charging decisions.”

In addition, although the test case was a relatively minor crime, the study’s authors found that a significant “subset of respondents recommended harsh sanctions.”

This may be due, in part, they wrote, to the absence of internal or national guidelines prosecutors report needing to follow.

“The findings from our exploratory study provide a starting point for future research assessing the variability and severity of prosecutors’ decisions.” Their findings also suggested the strong need for standards and guidelines in constraining discretion.