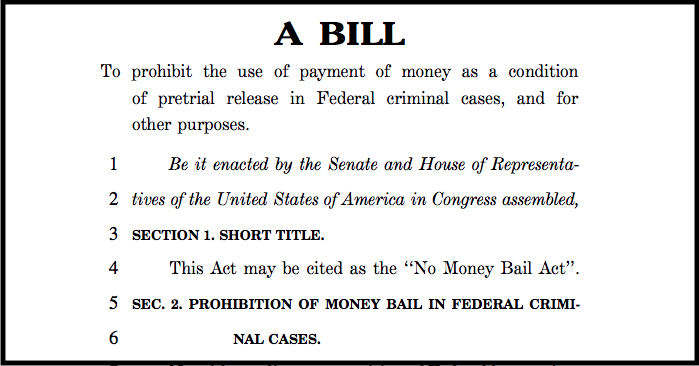

Last Wednesday, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) introduced a bill to prohibit the use of cash bail as a condition of pretrial release in federal criminal cases. The No Money Bail Act would also offer grants to states that want to implement alternatives to cash bail, and reduce their pretrial jail populations.

“We have criminalized poverty. That is not acceptable,” Sen. Sanders writes, in a column for NBC. “Pretrial detention should be not based on how much money a person has, what kind of mood the judge is in on a given day, or even what judge the case happens to come before.”

States that opt to keep their current monetized bail systems would be denied access to the funding. The bill would also require the U.S. Comptroller General to conduct a study three years after the bill’s implementation to make sure that the states’ new pretrial systems are not discriminatory, and are not “leading to disparate detentions rates,” according to the senator.

Sanders’ No Money Bail Act is a companion to a bill introduced by Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) in the House. Lieu says he looks forward to working with Sanders to reform the “irrational and dangerous” cash bail system. “The money bail system warrants sustained outrage because America should never be a nation where freedom is based on cash on hand,” says Lieu.

The two bills are the latest in a recent string of attempts at federal bail reform that have, so far, failed to garner enough support—on both sides of the aisle—to succeed.

Yet, nationally, rapidly expanding jail populations can be attributed, in part, to a growing reliance on pre-trial detention, according to a 2017 report from the non-profit Prison Policy Initiative.

In fact, a recent report from the Texas-based Republican criminal justice-focused think tank, Right on Crime, nearly three out of every four jail inmates in Texas are being held pretrial. The national average pretrial jail population is 66 percent—a not insignificant increase over the 50 percent rate in 1993. And rural jurisdictions are responsible for much of the increase, Right on Crime found. Rising jail populations can be addressed with comprehensive sentencing reform, according to the report, along with risk assessment tools, and pre-booking diversion programs, like the Law Enforcement-Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program piloted in Seattle, in which cops participate in referrals to community programs, before booking.

In an op-ed for the LA Times, R Street Institute’s Arthur Rizer and Shoshana Weissmann make the case for work release programs as a stopgap measure on the path to “sweeping jail reform” nationwide.

“Pretrial work release programs would allow defendants in jail, deemed eligible for bail yet unable to afford it, to return to their jobs or go to a new job while awaiting their trial,” Rizer and Weissman write. “Similar in function to standard work release programs for those convicted, pretrial programs generally order defendants, after completing their day’s work, to return to jail at night where they are supervised by correctional staff.” These programs would allow defendants to keep their jobs, while working toward making bail, at which point they could have full pre-trial release.

“All such programs would be good for counties’ budgets,” according to Rizer and Weissman. “In many states, taxpayers aren’t responsible for housing or supervising a defendant while they work. In some cases, a portion of the individual’s earnings goes toward the cost of housing the individual in the facility at night.” And when defendants make enough money to secure their release, counties save even more money, reduce their jail populations, and “can focus their resources on holding those who pose the greatest risk to society.”