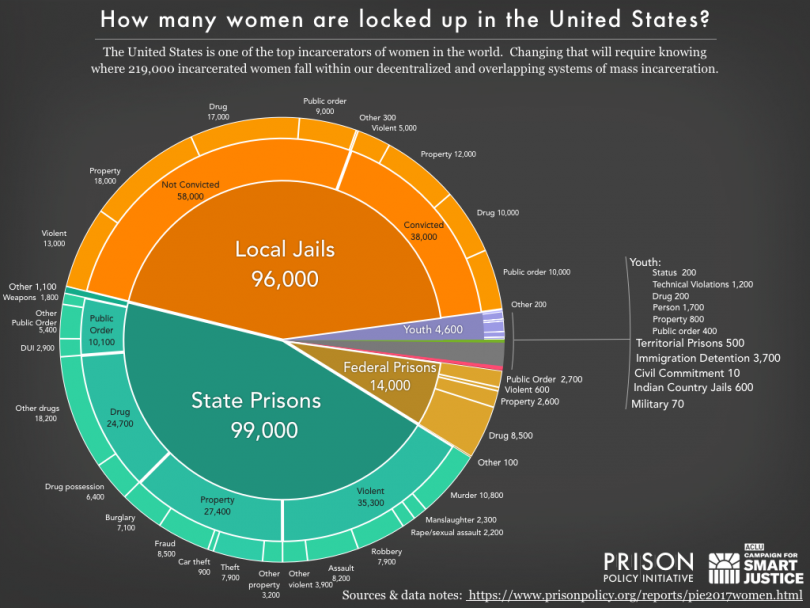

Slightly under half of the approximately 219,000 women incarcerated in the United States right now are in local jails, and 60 percent of these jailed women have not been convicted, but are still awaiting trial, according to a new report produced jointly by The Prison Policy Initiative and the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice.

The report, “Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2017”-—authored by Aleks Kajstura, the Legal Director of the Prison Policy Initiative—is an addition to a previous report released in March of this year, which looks at the issue of mass incarceration in general. The idea of the larger report was to piece together information from a wide range of reports on the various pieces of the incarceration puzzle: state prisons, federal prisons, county jails, Indian Country jails, youth facilities, and immigrant detention facilities.

This new report augments the first report by carving out a look at the incarceration of women in the nation’s jails and prisons, and the delving particularly into the ways that issues faced by incarcerated women are different from those of men.

Women Who Cannot Make Bail

The subject of cash bail is getting a lot of attention in the world of justice reform at the moment, and of the most interesting topics that the new report explores is the matter of making bail for pre-trial women, which appears to be particularly challenging.

Initially, however, one might deduce that the opposite is true, and that women would have an easier time than men in gaining pre-trial release.

For one thing, according to report by the Vera Institute titled Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform,” nearly 80 percent of the women in jails are mothers. But, unlike incarcerated men, they are, by and large, single parents, solely responsible for their young children, which means most judges consider them less of a flight risk.

Furthermore, the majority of the women waiting for trial, are charged with lower-level offenses—–mostly property or drug-related. These women also tend to have less extensive criminal histories than their male counterparts. In other words, the majority of the women in jail awaiting trial do not present a high risk to public safety.

With these facts in mind, the most recent available data suggests that “women generally receive greater leniency than men when judges, magistrates, or bail commissioners make pretrial custody and release decisions,” according to the Vera Institute report.

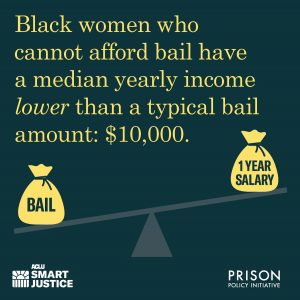

Yet, if bail is set, women are much less likely to be able to afford it than their male counterparts according to the Prison Policy Initiative/ACLU report.

The reason behind women’s inability to be able to post a cash bond, according to the Vera Institute report, “is a result of the wide range of social barriers many women involved with the justice system face,” but is also rooted in systemic income inequality.

“In 2014, all women typically earned 79 cents for every dollar all men earned,” wrote the Vera authors, “and this gap was much larger for women of color, with black women earning 63 cents and Hispanic women earning 54 cents to every dollar white men earned.”

A previous study by the Prison Policy initiative, Detaining the Poor, went even further, finding that women who could not make bail had an annual median income of just $11,071, which was nearly one third lower than the annual median income of men who could not make bail.

Black women unable to make bail had the lowest median annual income of all, $9,083 (just 20% that of a white non-incarcerated man).

“When the typical $10,000 bail amounts to a full year’s income, it’s no wonder that women are stuck in jail awaiting trial,” wrote Aleks Kajstura.

The Emotional Affect of Jail on Women

The subject of women in jail turns out to be particularly relevant in that, if they are convicted, according the new report, women are more likely to be sent to county jail rather than state prison, due to their generally lower level charges, which draw shorter sentences. “About a quarter of convicted incarcerated women are held in jails, compared to about 10% of all people incarcerated with a conviction,” wrote report author Kajstura.

But, aside from the shorter sentences, jails tend to be more problematic than prison for women. For one thing, according to the new report, jails make it harder to stay in touch with family than prisons do. Phone calls are more expensive, up to $1.50 per minute. For women with kids, particularly if they were sole caretakers when they were arrested, this is particularly traumatic.

Source: Shannon M. Lynch et al., Women’s Pathways to Jail: The Roles and Intersections of Serious Mental Illness and Trauma

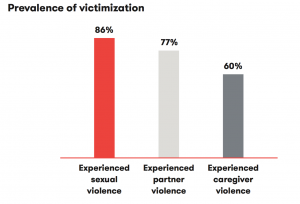

Overall, woman do less well emotionally in jails than than they do prisons, in part, say experts, in part because jails are primarily designed for men rather than women. Women are significantly more likely to suffer from mental health problems and experience serious psychological distress than either women in prisons or men in either correctional setting, according to an extensive report released in June 2017 by the USDOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics.

It doesn’t help that a startling 86 percent of women in the nation’s jails report having experienced sexual violence in their lifetimes, 77 percent report partner violence, and 60 percent report caregiver violence.

Spending time in jail itself can be a deeply traumatizing experience for women. Once there, women are far more likely than men to experience sexual victimization in jail. According to a 2014 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) report. Between 2009 and 2011, women represented approximately 13 percent of people held in local jails, but they represented 67 percent of victims of staff-on-inmate sexual victimization.

Furthermore, standard correctional procedures, such as searches, restraints, and use of solitary confinement, don’t take into account the violence and trauma the majority of incarcerated women have experienced outside of jail, since there is rarely adequate screening for this pre-jail trauma. As a consequence, such procedures as undergoing a full-body search for contraband, or being supervised by male staff while showering, dressing, or using the bathroom, for example, can trigger painful memories, can”reactivate trauma in women who have previously suffered abuse, in a different way than it does for men, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report.

The picture of women’s incarceration is far from complete, and many questions remain about mass incarceration’s unique impact on women, concludes the report’s author, Kajstura. “Based on our analysis in this report we know that a quarter of incarcerated women are unconvicted. But is that number growing? And how does that arguably undue incarceration intersect with women’s disproportionate caregiving burdens to impact families?

“Beyond these big picture questions,” writes Kajstura, “there are a plethora of detailed data points that are not reported for women by any government agencies, such as the simple number of women incarcerated in U.S. Territories.”

Yet, while more data is clearly needed, the information provided by this report points to a list of additional questions that the Prison Policy Initiative and the ACLU hopes will further point to the “policy changes needed to end mass incarceration—without leaving women behind.”