The right to a trial by jury is enshrined in the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and also in Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution itself. (“The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury.”)

John Adams, the nation’s second president, expressed the essential nature of the jury trial in dramatic terms. “Representative government and trial by jury are the heart and lungs of liberty,” Adams wrote just before the Revolutionary War. “Without them we have no other fortification against being ridden like horses, fleeced like sheep, worked like cattle, and fed and clothed like swine and hounds.”

Thomas Jefferson expressed a similarly strong opinion, although he phrased it slightly more elegantly.

“I consider [trial by jury] as the only anchor ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution.”

According to a new report just released by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, however, the jury trial has become such a rarity it is teetering at the edge of extinction.

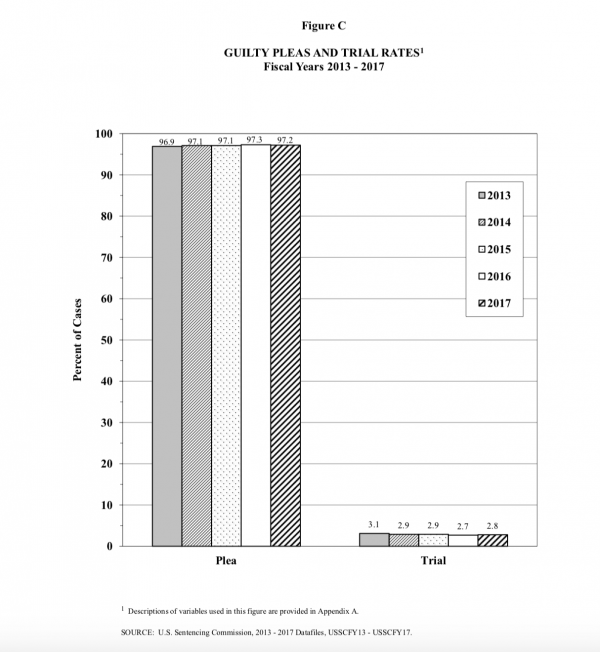

In fact, over the last fifty years, write the NACDL authors, trial by jury has declined to the point that it now occurs in less than 3% of federal criminal cases.

In state cases, that figure hovers at around 6%.

Thirty years ago, federal defendants chose to go to trial at least 20% of the time.

Not anymore.

Brian Banks and his lawyer from the Innocence Project at the dismissal of his wrongful conviction on rape and kidnapping charges, Long Beach, California, May 2012. Banks, who had been a high school football star with a scholarship to USC at the time of his arrest, served five years in prison for a crime he never committed after accepting a plea bargain under the advisement of his original lawyer. Photo courtesy of The Innocence Project

Today, according the report, which draws on records from the U.S. Sentencing Commission trials have been replaced by a “system of [guilty] pleas,” which have all but obliterated the role that the framers envisioned for jury trials “as the primary protection for individual liberties and the principal mechanism for public participation in the criminal justice system.”

The ACDL report—titled The Trial Penalty: The Sixth Amendment Right to Trail on the Verge of Extinction and How to Save It—points to a stack of evidence that criminal defendants—both at the federal and states levels–are being coerced to plead guilty because the penalty for exercising their constitutional rights to a trial is simply much too high to risk.

This “trial penalty,” as the report calls it, results from the discrepancy between the sentence the prosecutor is willing to offer in exchange for a guilty plea and the sentence that would be imposed after a trial.

Defendants still do have the choice of whether or not to go to trial, of course. But—according to the studies and exoneration data the report points to—the fears and pressures defendants commonly face in the plea bargaining process are so overwhelming, that in an alarming number of instances, innocent people decide to plead guilty to crimes they did not commit.

Specifically, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, of the 354 individuals exonerated by DNA analysis, 11% pled guilty to the crimes of which they were innocent. Furthermore, according to the report, the potential for such wrongful convictions is compounded because, in addition to forgoing a trial, in most plea deals the defendant must agree to give up many appellate protections that could later be used in post-conviction in legal challenges.

How we got here

Once upon a time, the nations appellate courts were very suspicious of plea bargaining, which began to be used more prevalently in the early twentieth century when, for a variety of reasons, crime was on the rise, causing the justice system to begin overloading.

MichaelMarshall,whopledguiltyafterbeingchargedwithaggravatedassault,armedrobbery, possession of a firearm during a felony, and possession of a firearm by a convicted felon, faced potentially decades in prison. He was sentenced to four years on a charge of theft by taking. Marshall later wrote a letter to the Georgia Innocence Project claiming, “I plead guilty out of being scared.” Marshall was released after DNA testing showed his DNA did not match the evidence from the crime. (Photo courtesy of the Innocence Project)

Plea bargains seemed like an excellent solution. A defendant could plead guilty to lesser charges in return for dismissal of more serious charges, and thus reduce their prison time. The case was resolved, the prosecutor had done his or her job. And the burden on the system was avoided.

Still, although the use of plea bargains was spreading, for decades, appeals courts viewed the practice with a jaundiced eye.

In 1941, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a defendant’s guilty plea induced by the prosecutor’s threat to seek a higher sentence was unconstitutional because the defendant had no counsel to help him assess the prosecutor’s pressure tactics. The high court wrote that the defendant in the case had been “deceived and coerced into pleading guilty.” Various related rulings followed over the next few decades.

Then, in 1970, the nation’s top court changed its mind on the topic of plea bargaining with a ruling known as Brady v. the United States (not to be confused with the famous 1963 ruling, Brady v. Maryland, about the necessity for the prosecution to turn over exclulpatory evidence).

With Brady v. United States, SCOTUS essentially authorized plea bargaining as a form of American justice.

At the same time, in the 1970’s and 1980s, as the crime rates that had been relatively low in the 1950’s began to spike due, in part, to the rise in drug-related crime, the systems once again began to overload.

With the climbing crime rates came the systems of mandatory minimums and sentencing guidelines, which had a significant effect on the system of plea bargaining.

As U.S. District Court Judge, Jed S. Rakoff, wrote in a 2014 essay for the New York Review of Books—the new guidelines and mandatory minimums provided “prosecutors with weapons to bludgeon defendants into effectively coerced plea bargains.”

Thus, what had been a useful element in the justice system, all but became the nation’s justice system itself.

The power of the prosecution v. the weakness of the defense

The problem was that, when it came to plea bargaining, the new sentencing structures suddenly handed prosecutors a disproportionate amount of power.

As Rakoff described it, at the beginning of most criminal cases, a defense lawyer meets with his or her client when the client is arrested or shortly after. Unless the client has the wherewithal to post bail, the defense lawyer most often has very little time in the early stages to find out the client’s version of the facts, much less to do the kind of fact-finding and investigation that presumably he or she would do before trial.

From the beginning, the prosecutor, in contrast, will have a full police report, including whatever witness interviews and evidence has been thus far gathered.

“Against this background,” wrote Rakoff, “the information-deprived defense lawyer, typically within a few days after the arrest, meets with the overconfident prosecutor, who makes clear that, unless the case can be promptly resolved by a plea bargain, he intends to charge the defendant with the most severe offenses he can prove”—-along with the longest sentence the guidelines will allow.

In other words, a plea bargain, while useful, suddenly was not anything resembling a deal made between equals.

About those huge sentencing “alternatives

Yet, the situation is complicated.

On one hand, if there were no discrepancy at all between what a prosecutor offered, and what penalty a defendant might receive if defeated at trial, the NACDL report acknowledges, there would be far less incentive for defendants to plead guilty.

But the gap between post-trial and post-plea sentences can be so wide, write the report’s authors, “it becomes an overwhelming influence in a defendant’s consideration of a plea deal.”

When a prosecutor offers to reduce a multi-decade prison sentence to a number of years — from 30 years to 5 years, for example —” any choice the defendant had in the matter is all but eliminated.”

That is the nature of what they have named the “trial penalty,” the authors write.

No check on an “all powerful prosecution”

The report argues that the vanishing of jury trials also deprives the justice system of, among other things, an important community-controlled check on prosecutorial excess.

The primary job of a jury is to determine whether or not the prosecution has met its high burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt before a someone’s freedom is abridged.

The jury also may convict a defendant of a lesser included offense, when the jurors deem the lesser offense, or offenses, are fairer and more just than those that the prosecution has asked for.

In other words, explain the report’s authors, a jury is the primary bulwark against prosecutorial overreach.

A jury of normal citizens provides a reminder, they write, that the “government is not omnipotent, but instead remains subject to the will of the people.”

When the U.S. criminal justice system “churns some 11 million people through its courtroom doors every year,” according to the report, the system of trial by jury “actively engages the public in this critical process of democracy.”

As trials become increasingly rare in the American criminal justice system, that essential brand of democratic engagement disappears as well.

So what to do?

So if the existing plea bargaining system really is this unjust and problematic, what is the solution?

In a paper published six years ago in the 2012 Utah Law Review, Belmont University law professor Lucian E. Dervan makes an interesting observation, having to do with that 1070 Supreme Court decision, Brady v. the United States, which effectively took most of the hobbles off the nation’s system of plea bargaining.

Embedded in Brady v. U.S., Dervan wrote, there is a solution that everyone seems to have forgotten.

“Brady,” he wrote, “contains a safety-valve that caps the amount of pressure that may be asserted against defendants by prohibiting prosecutors from offering incentives in return for guilty pleas that are so coercive as to overbear defendants’ abilities to act freely.”

Okay, so how does one determine whether the safety-valve has failed, and that prosecutors are, in fact, offering unconstitutional incentives?

Dervan noted that, handily enough, the Brady ruling actually provided its own “litmus test regarding innocent defendants.” The Court stated that “should the plea bargaining system begin to operate in a manner resulting in a significant number of innocent defendants pleading guilty the Court would be forced to reexamine the constitutionality of bargained justice.”

The bottom line, Dervan wrote, is that the U.S. justice system has a “significant innocence problem,” which in turn “indicates that the Brady safety-valve has failed.” As a result, “the constitutionality of modern-day plea bargaining is in great doubt.”

The NACDL report’s authors put it another way.

“A system that coerces even one innocent person to plead guilty,” the authors write at the report’s end, “should not be condoned. Nor should the rights of the accused to hold the government to its burden of proof be impeded by fear of severe retribution.”

This is not going to be a simple problem to fix, the report acknowledges. Yet, the authors also write, in their 78-page report, of their “grave concerns” that the current system “unfairly infringes” on one of our “most precious” Constitutional rights.

In other words, when the risks of exercising this crucial human right to trial are too great for all but 3% of federal criminal defendants, then “the system is in need of repair.”

The problem, agreed U.S. District Court Judge John L. Kane in a 2014 essay on the flaws of the plea bargaining system, “is that both innocent and guilty defendants are placed in the same pot and the goal is to achieve the appearance of justice, not the realization of it.”

The Sixth Amendment states “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.”

One of the key issues not raised in the article is bail reform. The author should have argued that the poor and indigent suffer the most – and that the system’s pump is primed against racial minorities….which it obviously is. They are desperate and want out. So they take the deal for a reduced prison or jail sentence – or probation.

If the author is so keen on this subject matter, then the point should have been raised as to discovery of exculpatory evidence. If defense counsel (typically an under-resourced Public Defender/Alternate Public Defender) has so little time to prepare, then the argument should be, in most cases for a waiver of a speedy trial. Truly innocent defendants should have no issue with this.

For those who are truly innocent and are the subject of grand jury indictment or a finding of probable cause resulting in hefty bail amounts, the price of their innocence pales in in comparison with the time spent in jail awaiting trial.

But I’m guilty!

In an article tagged “prosecutors” there is not a single quote from one nor is there a single reference to the prosecutors’ perspective on the matter. Judge Rakoff’s essay does not accurately reflect question 12 practices in many jurisdictions.

The report is NACDL‘s gripe is mostly about federal prosecutions which account for an extremely small percentage of all prosecutions.

Regardless, the NACDL report ignores the fact that judges — who also love the system of plea bargaining — engage in behaviors that encourage it perhaps to even to coerce it. And let’s not forget the guilty defendants and their lawyers who adore that plea-bargaining system which gives them a substantial discount off what they would get after trial. I cannot tell you the number of cases where a judge indicated the bare minimum sentence in order to induce a guilty plea before trial over my objection. Any forthright report would discuss these issues, the NACDL does not. Nor does this article.

“nor is there a single reference to the prosecutors’ perspective”

OK – let me fill it in for you – “we shouldn’t have to prove anything. The justice system is just a pipeline to prison for the vast majority of defendants, and its time we started acting like it!”