In 2011, Michele Infante was incarcerated for close to six months at the Century Regional Detention Facility in Lynwood, CA, a small city adjacent to Compton and Watts. The facility is Los Angeles County’s only jail designated for women and sprawls across an industrial zone in the shadow of the Imperial Highway. Infante, now 58, says she was sexually assaulted and sexually abused by two different employees at Lynwood, as the jail is known locally.

As she recalls, one day in late September 2011, after Michele had been at Lynwood for around five months, a deputy walked to the door of her cell and told her to come with him. He led her to what looked like an unused classroom in an empty wing of the jail, she said, then pushed her against the wall and raped her.

“When I went back to my room, I just remember crying. I didn’t get a shower for a couple of days, so I just felt so dirty and filthy,” she said. She didn’t have an extra pair of underwear to change into after the assault, and didn’t tell anyone what had happened. “I just felt so alone and isolated … and like I deserved it somehow.”

Now an activist with the grassroots organization Dignity and Power Now, Infante has spent nearly every weekend for the past four years standing outside the main entrance to the Lynwood jail, talking to women just being released about their experiences, how the deputies treated them, and whether they were able to stay safe while locked up.

It’s not the physical force women may experience so much as what she sees as the toxic power dynamics between prisoners and deputies at Lynwood that Infante worries about. The emotional fallout from her own time in lockup has left wounds that affect her close to eight years later.

“I have moments of depression if I’m alone and I’m not thinking about my work,” Infante said. “It definitely comes up, especially when I outreach on Saturdays and Sundays over at the facility where I was sexually assaulted.” Sometimes she will cry unexpectedly, she said. Since her release in 2011, Infante said, flashes of her time at Lynwood still find their way into her thoughts daily.

“The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department expects all of its members to hold themselves to the highest ethical and professional standards at all times,” an LASD spokesperson told WitnessLA when asked for comment on sexual misconduct at Lynwood. “Any proven criminal, or other acts of misconduct that violate public trust, will not be tolerated…The department is committed to the prevention of all sexual assaults and abuse in our jails.”

Long after her release, Infante reported her alleged abuse to former Sheriff Jim McDonnell at a town hall meeting in October 2014. Three letters followed from various members of the department who promised that the matter would be investigated, but in the end, nothing came of the complaint.

Sexual misconduct at Lynwood made headlines in the local news for close to two years. In September 2017, Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy Giancarlo Scotti was arrested for sexually assaulting two female inmates. By the following February, more women had come forward and Scotti was criminally charged with assaulting a total of six women between March and September of 2017. Since then, at least five women formerly jailed at Lynwood have filed federal lawsuits against Scotti and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) alleging sexual assault. His trial is scheduled to begin in September. In the meantime, deputy Scotti remains on administrative leave without pay, according to an LASD spokesperson.

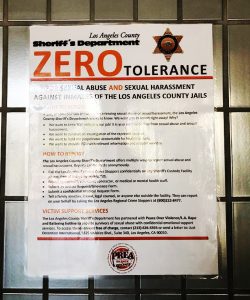

In March 2018 a preliminary audit of the jail’s compliance with federal sexual safety laws cited “serious and troubling allegations of sexual abuse and sexual harassment.”

Yet the kind of misconduct that doesn’t make headlines is arguably as corrosive, and harder to track than the overt assaults. It is also more common. This misconduct shows up in the form of subtler, almost mundane encounters between deputies and prisoners at Lynwood: the flirting in exchange for extra food, the exhibitionism in exchange for time outside one’s cell, the connections that mimic warmth or even love, but are defined as sexual abuse under federal law.

The majority of states, including California, have criminal statutes stating that inmates are not capable of consenting to sexual contact with detention facility employees, due to the obvious power differential; the guards have all the control in a locked facility. Of course, many individual deputies treat the women with professionalism and even kindness. But those who are not can make decisions that determine where a prisoner’s time inside falls on the spectrum from survivable to hellish, and prisoners must make decisions accordingly as to whether to report harassment, and risk reprisal, tolerate it, or get what benefit they can from a deputy’s sexual interest.

“The vast majority of the women who are locked up have histories of abuse, but also have histories of survival,” said Sheila Bedi, a clinical law professor at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law. “A history of abuse is a history of survival. It is a history of making intentional choices to survive.”

Sometimes, the dynamics in lockup can echo the situations that took place on the outside. “Because women are making intentional choices about what they have to do in order to survive, it doesn’t lessen the culpability of their abusers, whether their abusers work inside the prison or on the street.”

“There can be no consent”

“Sexual misconduct” in a jail or prison doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone, and that makes tracking it all the more difficult. The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), a set of laws passed in 2003 which aim to increase sexual safety in lockup, deems any kind of sexual contact between an inmate and a corrections officer illegal, whether or not that contact appears to be consensual. But some prisoners who have regular sexual contact with deputies consider themselves to be in consensual relationships. Likewise, a woman who gets extra food or time outside her cell because of a deputy’s attraction to her likely has no incentive to report that arrangement.

Tameshia Green, 32, was released in December 2017 after three years in Lynwood. In that time, she said, she never witnessed, experienced, nor heard about a sexual assault in the facility. But she described one guard who she says “liked” her, who would walk past her cell and tell her she looked good.

“It was kind of crazy, but I said hey, I got to use what I got to get what I want,” Green said. In exchange for extra food and other necessities, she would walk naked around her cell, making her body visible to the guard who praised her appearance. There was never any physical contact between them, she said.

To Green, the officer’s alleged quid pro quo behavior didn’t qualify as harassment, though the law is clear that it did.

“The bottom line is, given the power dynamics in prison,” said Sheila Bedi, “given the absolute control that authorities have over the lives of people who live behind bars, there can be no consent in terms of what the law defines as consent and there can be no consent in terms of equal power in the interaction.

“The officers who are trading sexual acts for different types of favors,” Bedi said, “that often is a part of grooming that often is a first step toward physical contact. We’ve seen that happen over and over again.”

Author Leslie Schwartz, who spent 37 days at Lynwood in 2014, said she observed a lot of what she called “obvious, clear flirtations” between women and staff, and noted that the female inmates who “knew how to work it” were able to secure certain privileges. On a few occasions, Schwartz said she was able to see a package from her husband waiting for her, but the deputy who should have given it to her immediately simply chose not to.

“It wasn’t even personal,” she said. “It was just ‘you’re scum, you’re one of the maggots in this place’.”

Later in her stay, Schwartz got a roommate whom she described as “cute,” and who was willing to flirt with the deputy in charge of distributing mail on her behalf. That way, Schwartz said, she was able to get her packages without delay.

Schwartz, and several other women who spoke to me about their experiences at Lynwood, observed relationships between women and deputies that appeared to be consensual. Schwartz recalled a young woman and an older deputy who were in an ongoing relationship, and whom she once saw emerging hand in hand from the bathroom near the guard’s station on her module.

“They were always talking to each other, they were always together. Everybody knew,” Schwartz said. “It wasn’t something they were hiding.”

April Villestas, 49, has done multiple stints at Lynwood, most recently in May 2015. She said that ongoing sexual relationships between women and deputies were common, and that rendezvous would take place at night when most women were sleeping.

“The next day I would hear about how so-and-so got to be out all night with this male deputy,” Villestas said. “I’ve been in a lot of those dorms. It’s happening all over that jail.”

Villestas remembered one week in particular during her most recent stint at Lynwood. Several times that week, she said, during the day and during the night, deputies would allow one woman to visit her girlfriend’s cell privately, and would guard the door while the two women were alone together. Villestas noticed that the deputy who facilitated these visits during the night would stand watching the two women through the window in the cell’s door.

“I believe that was her payment for allowing it to happen,” Villestas said.

After she was released from Lynwood, Villestas ended up at a rehab facility in Long Beach where one of the women in the couple was also staying. Villestas asked her if she knew that the deputy was watching her and her girlfriend when they were ostensibly alone together. Yes, the woman told her, but she didn’t care. At least she got to be with her girlfriend. Besides, she said, she and the deputy liked each other, and she got special privileges because of that attraction.

Villestas was floored.

“It’s disgusting,” she said. The way [the deputies] treat us, it’s like we’re animals. We’re addicts. Okay. But what is their reason for being disgusting?”

Elizabeth Swavola, Senior Program Associate at the Vera Institute of Justice and co-author of the 2016 report Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform, said that people tend to have the perception that women in lockup deserve punishment and harsh treatment, despite evidence that the majority of women are in jail for nonviolent offenses and 30% have serious mental health issues.

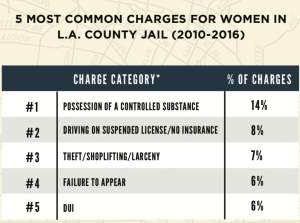

According to a January 2019 report by UCLA’s Million Dollar Hoods Project, the five most common charges faced by women sent to Century Regional Detention Facility over the past seven years were possession of a controlled substance (14 percent), driving on a suspended license or with no insurance (8 percent), theft, shoplifting, or larceny (7 percent), failure to appear (6 percent), and DUI (6 percent).

“It’s really hard to get people to care about women in jail,” Swavola said. “The #MeToo movement has really moved us forward as a society and shone a light on how pervasive sexual violence and abuse is. But I haven’t seen as much attention to women who are incarcerated.”

Recent, reliable data on women and jails are scarce, Swavola said, but the data that do exist suggest that the overwhelming majority of women who comprise the US jail population have histories of complex trauma, making them more vulnerable to abuse. A small-scale 2012 study by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, for example, found that 86% of women in jail have experienced sexual violence in their lifetimes, and that 53% have “lifetime” post-traumatic stress disorder.

Leslie Schwartz said that based on her time at Lynwood, the 2012 DOJ study’s finding that 86% of women in jail had experienced sexual violence in their lives seemed low. Schwartz said that every woman she spoke to in the jail “had been in some way sexually abused by a man, husband, brother, stranger.”

An absence of data

A preliminary audit report on Lynwood’s compliance with PREA standards was leaked to the Los Angeles Times in April 2018. The report found that the facility met just 2 of 43 safety standards.

On February 12 of this year, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors approved a $950,000 settlement for a former Lynwood prisoner who was one of those who reported she was sexually assaulted by a deputy while inside.

Beyond these glimpses into Lynwood, specific data on the extent of sexual misconduct in the facility is difficult to obtain. For one thing, it’s unclear whether allegations of misconduct have been systematically recorded, an issue that perplexed the PREA field audit team during the course of their six-month investigation. The team noted several times in their 138-page report that their work was hampered by a lack of access to the data and documents they requested, including “investigative, personnel, medical, and mental health files onsite, which is key to conducting a performance-based audit,” the auditors wrote.

Karen Dalton, the PREA coordinator for the LA County Sheriff’s Department, pointed out that the department itself requested the preliminary audit, knowing full well the report would paint a grim picture of sexual safety and PREA compliance at Lynwood.

The effort to bring LA County’s jail facilities into compliance with federal laws around sexual safety began in 2015, and has progressed since the preliminary audit report was leaked last year, according to Dalton. But those efforts have been hobbled by the fact that, until last November, Dalton was LASD’s sole full-time staff person dedicated to PREA.

The abysmal field audit report “opened a lot of eyes,” Dalton said, and resulted in an LA County Board of Supervisors motion last May to allocate more PREA staff to the sheriff’s department. (One manager came on board in November 2018, and another began April 1, 2019).

Dan Baker, Chief Deputy for the county’s independent oversight body, the Office of the Inspector General, said the OIG is made aware of all sexual assault grievances from CRDF that the department receives. “And our staff continues to monitor the department’s handling of those grievances and its progress toward meeting the PREA requirements,” said Baker. “Monitoring the department’s compliance with PREA is something we are taking very seriously here.”

Underreported sexual assault is another obstacle in gauging the scope of sexual misconduct at Lynwood. Sexual assault is universally underreported, both inside and outside of correctional facilities, due to a fear of retaliation or of being disbelieved, or the stigma around being a victim of abuse, or a misplaced sense of guilt.

Esther Lim, former director of ACLU Southern California’s Jails Project, now the Director of Monitoring & Policy for the Correctional Association of New York, believes that the majority of sexual misconduct at Lynwood goes unreported. When she conducted visits to the jail, Lim said, women were forthcoming about experiencing verbal abuse, but much less so about sexual assault.

“Because of the sensitivity around reporting [sexual misconduct],” she said, “we would sometimes hear, ‘I don’t feel comfortable telling you now, but maybe when I get released, I might.’”

Finding safety

When she was inside, Infante suspected she wasn’t the only woman at Lynwood who had endured violence or negligence that resulted in real harm. In her first week in general population, she said, she saw through an open bathroom door a woman on her knees and a deputy adjusting the front of his pants.

“It was just like these things happen,and there’s nobody to turn to,” Infante said. “The girls would say if you turn in a complaint or grievance, the only thing that’s going to happen to you is you’re going to be retaliated against, and you’re going to wind up staying in there even longer. To say that I was scared is an understatement.”

In the beginning, Infante stayed quiet about the alleged assault.

Then one morning in October, three or four weeks later, Infante had a medical appointment to get an x-ray. When she was alone in the room with a medical staff person, she said, he unzipped his pants and started masturbating in front of her. Infante fled the room and spent the next several hours in her cell, trying to think clearly enough to figure out what to do.

“I couldn’t take it anymore,” Infante said. “At that point in time I honestly felt suicidal, and I had never been suicidal in my life before.”

So she waited a few more hours until the next time she was allowed out of her cell, picked a deputy she’d never spoken to before, and approached him. She told him about the incident that had just taken place with the medical staff person, as well as the assault a few weeks earlier.

“How long have you been here?” Infante recalled him asking.

“For about six months.”

“Well, I think what happened is that you want to get out of jail so bad that in your mind, you fabricated this so that you could get out,” said the deputy.

No, Infante said she told him. “I did not fabricate what happened. And if you don’t believe me, when I get out, I will go to the San Gabriel Valley Tribune and the Los Angeles Times,and I will let them know what happened.”

The chutzpah Infante showed in making the threat worked in her favor. That same night around 2AM, Infante said, she was awakened by a deputy tapping her on the shoulder and calling out her name. She knew what was happening. She was about to be released, less than 24 hours after reporting the sexual abuse to a deputy.

While she was being processed out, she said, no one asked her about the sexual assault allegations she had made to the deputy earlier. “I believe that they were hoping that…they would release me and I would never want to come back and talk about it.”

Infante was free, but she didn’t feel free. She still doesn’t.

This story is part of a WitnessLA series made possible with the generous support of the Fund for Investigative Journalism and is co-published with The Guardian.

Photo at top of Century Regional Detention Facility by Tobin Yelland

Get this and other essential justice stories delivered directly to your inbox by subscribing to The California Justice Report, WitnessLA’s weekly roundup of news and views from California and beyond. Read past editions – here.

I worked MCJ back in the 80’s and got drafted a few times to work at SBI. As a young and naive 21 year old I was astounded that the Department allowed men in a women’s facility at all. Many of the female inmates were aggressive and would walk around naked trying to entice deputies. It was very uncomfortable and I could see how men would make stupid mistakes if they worked there full time. As a matter of fact a few of my classmates were fired for inappropriate interactions of some sort with females. Likewise, I remember a female custody assistant at MCJ having relations with a inmate. Biology being what it is, it makes no sense to mix men and women at all. It has always been a recipe for disaster and will continue to be in the future.

During my stints at several custody facilities as a deputy, I know for a fact that the contents in the inmate complaint box always mysteriously disappeared.

Maybe things have changed now and the complaint box is probably near a Sgt’s office with a video monitoring it.

I never understood why the department felt it necessary to mix sexes in the jail for staff. Opposite sexes never worked staff stations of the opposite sex (female office in a male area and visa versa) in the past. Male inmates flopping their manhood out for the female staff member and the female inmates were no better. Guess what, a staff member feels wanted and gets caught up in the love bug, or worse, simply a piece of SXXX rapist who violates somebody because he or she can.

Perverts are perverts and they always will be. The department pulls its personnel from the general public we serve so we have them. Like the EM shift deputies that drive around looking for couples getting it on in their car in hopes of getting a glimpse of a show.

Unfortunately Ms. Dalton (not a sworn member of the department) is so busy with projects she could never find the time to properly handle PREA. Another project or requirement the sworn executives felt was unworthy of their time so it goes to Ms. Dalton.

Jail is jail and happy we have it for the crooks who fail to comply with societies rules, but, nobody deserves to be sexually violated – period. Inmate on inmate or staff on inmate, simply wrong and I think everybody with any sense would agree.

You would think jails would have so much surveillance going on that there would not be a corner somebody could slip into and hide. Not so. I have seen deputies point what should be the dorm overwatch camera to the TV to watch what the inmates watch since the deputy could not have a TV in his or her staff station. Boredom creates ingenuity.

[…] California Jail where Women Say Guards and Medics Preyed on Them, published by The Guardian, and WitnessLA, Lauren Lee White, describes an even more toxic abusive culture where guards and other officials […]

i think only female gaurds should work at any womens jail….my x girlfriend has mentioned something to her and gaurds at lynwood jail but wont admit any guilt…i know my x and i would say shes guilty of having some kind of sexual interactions with a male gaurd while her 40 days at lynwood from april to june 2019

Uncrualty. Punishment for only ur sexual prefrence . to lesbian community in heidy castellanos she us citizen born 4.13.1982

Cruel and sexual and mental abuse womens in lynwood crdf. Misstreating mental disable inmates