Moving quickly in response to protests and demands to overhaul public safety in Los Angeles, city councilmembers introduced a pile of motions last June to explore options for changes to the 911 system, emergency response, and other aspects of policing.

The city is making progress on its efforts to reimagine 911 and emergency response to eliminate the need for law enforcement to answer non-violent mental health, homeless, and substance use-related calls.

Many of the other motions, however, have not made it before the full LA City Council for a vote seven months after their introduction.

Motions to Expand Violence Prevention Efforts and De-Escalation Models Gather Dust

Here’s the lineup of some of the most important motions, and where they stand:

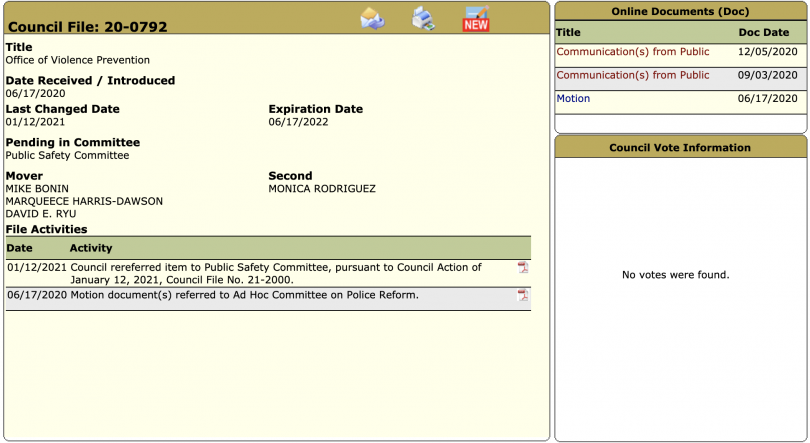

One motion, introduced on June 17, 2020, calls for a report back on the feasibility of creating an Office of Violence Prevention that “could house resources for communities to establish such plans and respond effectively to crises before they begin.”

“Such an office would employ civilian teams, or contract with a non-profit organization, to work within communities to create public safety plans unique to their neighborhoods and then implement them,” the motion states. “Once established, when situations of interpersonal conflicts arise, mediators, conflict interrupters, and restorative justice teams could answer the call if no one’s safety is at risk.”

The motion notes that other jurisdictions have had success with violence prevention departments, including Minneapolis. (LA County, too, has an Office of Violence Prevention housed within the Department of Public Health.)

Introduced by Councilmembers Mike Bonin, Marqueece Harris-Dawson, and David E. Ryu, and seconded by Councilmember Monica Rodriguez, the motion was sent to the council’s Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform, where it sat until January 12, 2021, at which time, the council voted to have the Public Safety Committee absorb the ad hoc committee.

Another motion regarding the possible expansion of the LAPD’s Mental Evaluation Units (MEU) and Systemwide Mental Assessment Response Teams (SMART), introduced on the same day, June 17, has faced the same delays. The motion calls for a report back from the LAPD regarding what resources would be needed to increase the number of MEU and SMART teams, which pair mental health clinicians with law enforcement officers to more effectively de-escalate mental health crises.

Also among the motions awaiting action is a June 10, 2020 motion to look into expanding the city’s Community Safety Partnership, through which LAPD officers are assigned to specific public housing developments for five years. These carefully selected officers are tasked with forming relationships with the residents in a non-adversarial way, by doing things like coaching youth sports, leading Girl Scout troops, and walking kids to school. CSP is run in partnership with the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA), and the Advancement Project.

The CSP motion notes that a recent in-depth review by UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs found that while the program was not without flaws, it had helped to reduce crime and police shootings, make residents feel safer, and improve murder clearance rates — because witnesses were more willing to talk to the CSP officers.

A fourth motion directing the LAPD to move forward with peer intervention training, “which instills the expectation that officers have a duty” to intervene when a fellow officer uses excessive force against civilians or commits other forms of misconduct, was first sent to the Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform on June 16.

George Floyd, the motion said, might have lived had the other Minneapolis police officers who watched Derek Chauvin choke Floyd to death for nearly nine minutes received peer intervention training.

The peer intervention motion was approved by the Public Safety Committee on August 11, and sent back to the ad hoc committee where it remained until the subcommittee was absorbed by the Public Safety Committee in January.

Reimagining Traffic Enforcement

In June, councilmembers also proposed a motion that would direct the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) and the Office of the Chief Legislative Analyst (CLA), to work with community stakeholders to report on alternatives to having armed law enforcement officers responsible for traffic enforcement.

In July, the Berkeley City Council adopted a related motion by Councilmember Rigel Robinson “to pursue the creation of a Berkeley Department of Transportation (BerkDOT) to ensure a racial justice lens in traffic enforcement and the development of transportation policy, programs, & infrastructure.”

Proponents say Berkeley is the first jurisdiction in the nation to vote to take traffic enforcement out of the hands of law enforcement.

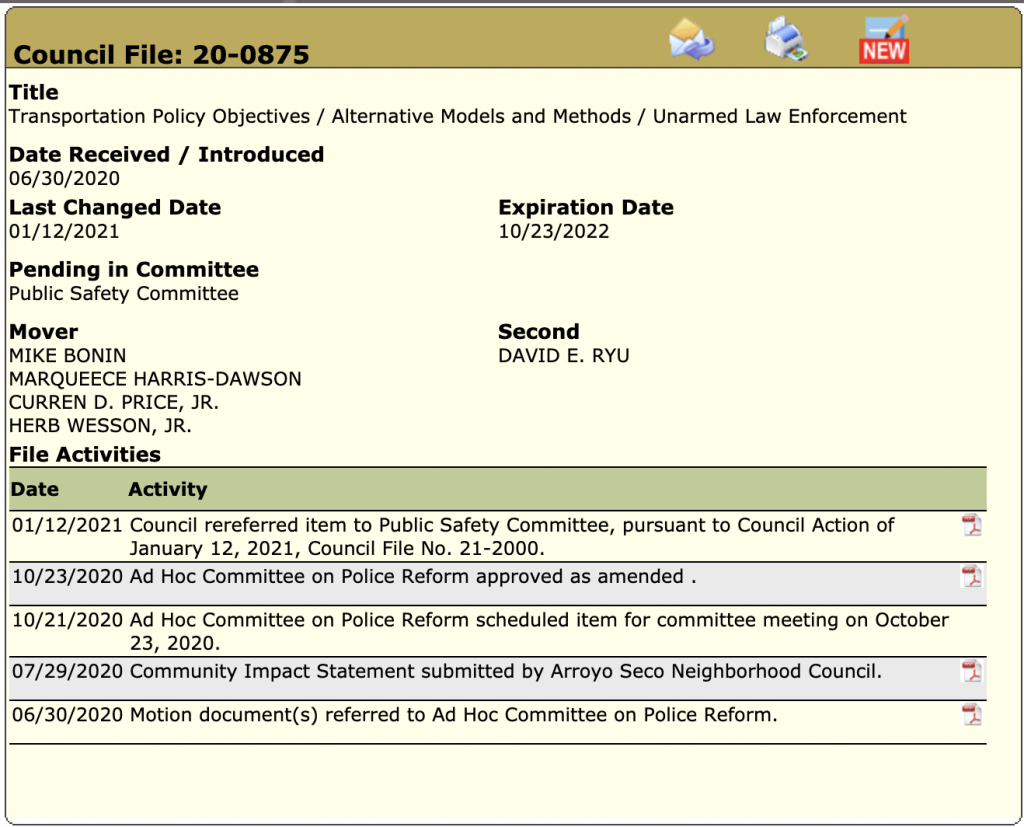

LA’s measure, introduced by Councilmembers Marqueece Harris-Dawson, Mike Bonin, Curren Price, and former Councilmember Herb Wesson, wouldn’t even go so far as to commit to creating an alternative traffic enforcement system. Instead, it calls for a preliminary report on potential models that would remove “traffic enforcement, moving violation and vehicle code enforcement, DUI details, traffic collision reporting and investigation, fare enforcement,” and other types of transportation-related enforcement from among the LAPD’s responsibilities.

The requested report would look at best practices elsewhere and at what resources the department currently receives from transportation sources. It would also include recommendations for having the LA Department of Transportation take over these areas of enforcement, as well as look into how the city might “utilize automated enforcement methods, and/or reallocate resources to public safety strategies that are more effective than enforcement.”

Across the nation, police “have long used minor traffic infractions as a pretext for harassing vulnerable road users and profiling people of color,” the motion says. “From jaywalking citations in Downtown and Skid Row to operations by the Metropolitan Division in South LA, the Los Angeles Police Department’s history of misusing traffic enforcement has fostered decades of distrust in communities of color that ultimately undermines true traffic safety initiatives.”

The latest annual report on racial and identity profiling based on stop and search data submitted to the California Department of Justice looked at nearly 4 million stops that the state’s 15 largest police agencies — including the LAPD and the LA Sheriff’s Department — conducted between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2019.

The report revealed — among other disparities — that 15.9 percent of the stops were of Black people, despite the fact that Black people comprise 7 percent of the state’s population.

Similarly, officers searched approximately 8% of white people they stopped, but 20.5 percent of Black people — the highest rate of any racial or ethnic group. Yet, searches of white individuals were more likely to turn up “contraband” or evidence than searches of those who were Black.

Approximately 12.1 percent of the reported stops occurred because law enforcement officers had “reasonable suspicion” that the stopped individual had engaged in some kind of criminal activity.

Almost all of the rest — 85 percent of the nearly 4 million stops — were initiated in response to traffic violations, according to the agencies’ data.

“Philando Castile was pulled over for a broken brake light,” Berkeley Councilmember Robinson wrote in his motion. “Sandra Bland was pulled over for failing to signal a lane change. Maurice Gordon was pulled over for speeding. All three died at the hands of police.”

PUSH LA Coalition Calls for City Council to Act

The alternative traffic enforcement motion, which was introduced on June 30, 2020, was first sent to the Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform. The ad hoc committee’s members scheduled the motion for a meeting on October 21, and approved a revised version two days later, calling for a request for proposals from consultants who could study the feasibility of unarmed traffic enforcement.

Bold, all-caps text at the bottom of the amended motion reminds readers that the proposal is “-NOT OFFICIAL UNTIL COUNCIL ACTS-” however.

Nearly three months later, when the subcommittee was disbanded on January 12, the motion was returned to the Public Safety Committee.

PUSH LA, a group of community organizations focused on investing in communities while divesting from criminalization, presented the council with a letter last week urging them to act on the motion related to transferring traffic enforcement to a non-law enforcement department of transportation.

When the motion was introduced in June, “we were hopeful,” PUSH LA leaders wrote. “Now, more than seven months later, we are beyond frustrated by the Council’s inaction on a motion that could help address the scourge of state violence on Black and Brown communities.”

(PUSH LA’s members include the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California (ACLU SoCal); Advancement Project CA; Black Lives Matter Los Angeles; Brotherhood Crusade; Brothers, Sons, Selves; Children’s Defense Fund California; Community Coalition; Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA); LA Voice; Labor Community Strategy Center; Million Dollar Hoods; SEIU 2015; SEIU Local 99; and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Southern California.)

“Our people require URGENT ACTION by their City Council,” PUSH LA’s letter says. “We demand that this motion be agendized for a vote by the full Council so the mandated action can begin instead of being sent to yet another committee.”

When the council reorganized its committees on Jan. 12, the apparently delayed motions were referred to the Committee on Public Safety, chaired by Councilmember Monica Rodriguez.

Between July 1 and January 12, the Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform met just twice in October. The public safety committee met seven times in that span.

“All motions related to alternative models just became part of the purview of public safety committee in January (approx 15 days ago),” Rodriguez’s office told WitnessLA. “The AdHoc Committee on police reform was not a committee the Councilwoman chaired or previously served on. For that reason she sought the merger of these committees so as to not have decisions made in isolation.”

Councilmember Rodriguez, said Communications Director Laura McKinney, “is leading these conversations this year in a comprehensive manner that also underscores our need to reform investments in youth as part of our citywide strategy.”

As of Feb. 8, 2021, the Public Safety Committee had met once since Jan. 12, but had not addressed the motions to reimagine public safety in LA.

Back in October, when the police reform subcommittee met twice, LAist reported that several of the police reform motions, including the alternative traffic enforcement motion, were moving on to a full council vote, Former Councilmember Herb Wesson said he was “giddy as a school boy.”

“I cannot wait to begin,” Wesson said at the beginning of a committee meeting. “Because I truly believe… that we’re going to send a message throughout this country.”

That urgency, Leslie Cooper, Vice President of Organizational Development at Community Coalition told WitnessLA, appears to have evaporated.

Well who could have seen this coming? Trump out of office, and all of a sudden the defunding and the reimagining evaporate into the political ether. Pretty obvious political shenanigans really, I don’t imagine too many people were fooled. (Other than witness la and cf of course)

Also I couldn’t help but notice no one appeared to be kneeling at the Super Bowl, nothing but mega cooperate bliss, so it looks like the election of Joe Biden solved that little problem too.

[…] Although there may be consensus on the need for change, unwinding the city’s historic over-reliance on police officers and developing a crisis response based on human services and health will take an enormous amount of money and effort. The money transferred from the LAPD budget could help get that ball rolling. But proposals to send crisis intervention workers to nonviolent 911 calls and to use civilian traffic agents instead of cops remain ideas on paper, languishing in committee. […]

Why this prolonged City Council deliberation about how public safety can be administered by a law enforcement that has historically threatened the public safety of Black and Brown people? Why is there hesitation in recognizing that public safety for Black and Brown people can only be achieved by transformation of the LAPD into a weaponless, community focused, investigative, highly educated social working entity that works intimately with and for ATI programs? This hesitation makes suspicious the LAPD’s hold on the City of LA. Doesn’t a heavily funded, weaponized force question whether the LAPD has successfully separated itself from the task of slowing minority expansion?