On Friday, President Joe Biden officially declared today, October 11, 2021, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, “a holiday dedicated to Native American people, their rich histories, their art, literature, and their irreplaceable general cultures.”

The Prison Police Initiative chose to observe the holiday by creating another kind of reminder, namely by showing how Native people are harmed in unique ways by the U.S. criminal justice system.

In order to illustrate, the PPI has offered a data-driven roundup of some of the ways Native people are impacted by prisons, jails, and police.

PPI research analyst Leah Wang, the new report’s author, has also focused on the persistent gaps in data collection and disaggregation “that hide this layer of racial and ethnic disparity,” she writes.

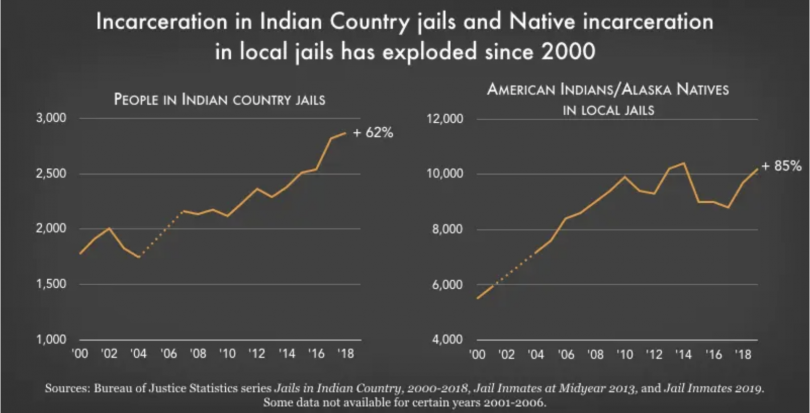

According to Wang and the PPI, in 2019, the latest year for which data was available, there were over 10,000 Native people locked up in local jails, a number that is up a staggering 85% since 2000.

Those figures, however, do not include those held in Indian country jails,** located on tribal lands. The numbers for Indian country jails increased by 61% between 2000 and 2018. Meanwhile, the total population of Native people living on tribal lands decreased slightly over the same time period.

The numbers get even worse in federal lock-ups where Native people made up 2.1% of those federally incarcerated in 2019, more than double their percentage of the total U.S. population, which was less than one percent.

Similarly, Native people made up approximate 2.3% of people on federal community supervision in mid-2018.

Wang points out that the reach of the federal justice system into tribal territory is “complicated” because state law often does not apply, and many serious crimes can only be prosecuted at the federal level, meaning sentences can be harsher than they would be in state courts.

“This confusing network of jurisdiction sweeps Native people up into federal correctional control in ways that don’t apply to other racial and ethnic groups,” writes Wang.

Even more disturbing, yet sadly not surprising, Native women are particularly overrepresented in the incarcerated population, according to PPI’s data.

Although Native women were just 0.7% of the U.S. population, in 2010, they made up 2.5% of women in prisons and jails.

As WitnessLA has reported in the past, incarceration of women has grown at twice the pace of men’s incarceration in recent decades both in local jails, and in state prisons, particularly incarcerated women of color.

When it comes to native women, their over-incarceration represents only one facet of the devastating human rights crises facing Native women, which prominently includes the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and the high rates of sexual and other violent victimization.

Even worse, according to the PPI report, are the disparities in how Native youth are treated by the juvenile and criminal justice system.

(The good news and the bad news, is that the numbers for kids are a bit better-documented.)

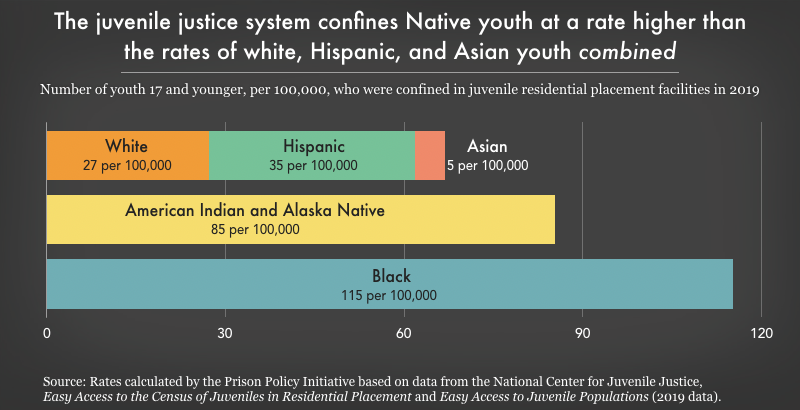

Native youth confinement rates, exceed those of white, Hispanic and Asian youth combined. Only black youth have higher rates of being locked up.

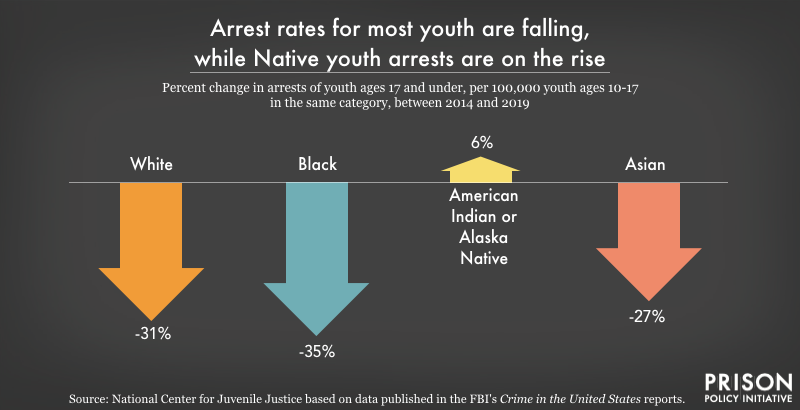

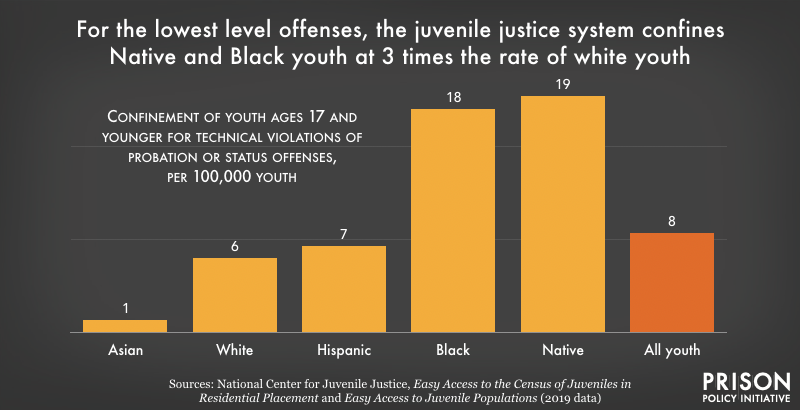

Some of the elements that have formed this disparity include disproportionate arrest rates of Native youth for certain kinds of offenses, such as school-related arrests, along with harsher outcomes for court-involved youth, particularly for low-level offenses like technical violations of probation and status offenses.

In absolute numbers, there are of course fewer Native youth than there are white, Black, Hispanic, or Asian youth.

Yet, the rate at which they are in contact with police and youth confinement facilities is alarming, as the PPI documents.

Centuries of historical trauma are manifesting in Native youth as mental health and substance use issues that go untreated, and can lead to status offenses (acts that are only criminal because of one’s age, like skipping school) or other “delinquent” behavior.

And the story goes on from there.

The conclusion that the PPI report points toward is this: On a day that the sitting president — plus 14 states (California not among them), the District of Columbia, various local jurisdictions (including Los Angeles County, the city of Los Angeles, and more than 130 other cities) — have dedicated to Native people, ait is “critical to understand how Native people on both tribal and non-tribal lands are overcriminalized.”

Hence their report, and this story.

** The PPI notes that that the term “Indian country,” in this context, is a legal term referring to land within American Indian reservations and other Native communities and allotments. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects and publishes data about jail facilities on these lands separately from other locally-operated jails in the U.S. According to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the term “Indian Country” – with a capital “C” – “is used with positive sentiment within Native communities, by Native-focused organizations such as NCAI, and news organizations such as Indian Country Today.”

The research you cited is flawed. The researchers excluded 5.9 million American Indians and Alaska Natives from their data analysis because they identified as mixed race (AI/AN + another race). This results in an invalid data analysis and flawed numbers pertaining to this population. In order to obtain a true picture of the impact the Criminal Justice System is have on the Native population in the United States ALL Native people need to be included, NOT just the full-bloods.