Between 2006-2015, arrests of girls in the U.S. dropped by 53 percent, from just under 580,000 to fewer than 270,000, and accounted for fewer than one-third of all juvenile arrests, according to newly released data from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP).

Additionally, the number of girls in juvenile court and in residential placements has dropped to levels not seen since the 1990s.

The Vera Institute of Justice aims to see the trend continue, all the way down to zero, through its new national “Initiative to End Girls’ Incarceration” campaign.

“Getting to zero” girls in lockup within the next decade, is an “ambitious but achievable” objective, according to Vera.

Annually, fewer than 46,000 girls are incarcerated each year–a significant drop from the nearly 100,000 girls incarcerated annually in the early 2000s.

In 2015, most states had fewer than 150 girls serving long-term sentences in juvenile facilities.

But there is still much to do to address the issue of the smaller but still significant population of incarcerated girls, many of whom are locked up for low-level offenses, and could be better served by evidence-based programs at the community-level. “While these numbers are exciting, what’s happening with the small population that is left in these girls’ facilities is unjust and—for the most part—not talked about,” Vera researchers state.

“They are disproportionately poor girls and gender expansive youth of color who have endured instability, lack of family resources, gender-based violence, and trauma, only to be pushed into custody when child-serving systems fail them.”

The needs of the nation’s locked up girls “have gone unmet” in their communities, Vera says. “The girls who experience the harms of this confinement are disproportionately girls of color, LGB/TGNC, poor, in foster care, survivors of violence (especially family and sexual violence), and victims of sex trafficking.”

We must not continue to “leave these girls behind,” according to Vera. “The juvenile justice system is neither intended nor able to provide the long-term solutions needed to ensure the well-being and safety that they deserve,” the institute states.

Indeed, kids often face violence and abuse in juvenile detention facilities, and research shows that locking up minors makes them more likely to end up in jail as adults than their peers who were not sentenced to spend time in a detention facility.

Girls’ incarceration rates are falling more slowly than that of boys, data shows. Part of the problem, Vera says, is “a lack of systemic focus on reducing girls’ confinement.”

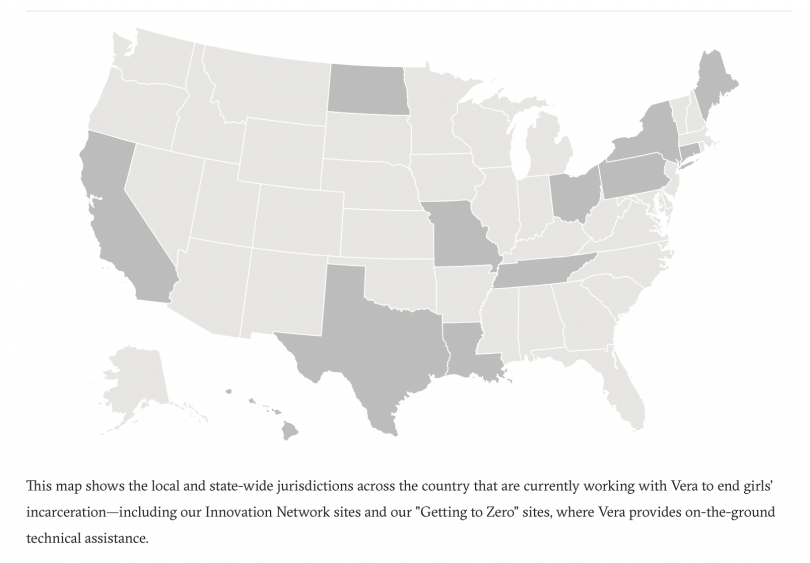

Vera’s new initiative will focus on working with jurisdictions that are “ready” to look at and ultimately address “the gender and racial inequalities that exist across their child-serving systems,” in order to keep girls out of the justice system.

Two years ago, Vera collaborated with New York City to launch a local “Task Force to End Girls’ Incarceration.” Since then, the project has helped to reduce the city’s number of girls in long-term lockup from 56 to 17.

Last year, Vera extended similar technical assistance to sites in nine states, including Santa Clara County, in California, to develop and carry out comprehensive decarceration plans that include changes to policy, practice, and programs.

The newly announced expansion of this work will employ a three-pronged strategy.

The initiative will target the nation’s “top incarcerators”–focusing on eight states that are responsible for more than 50 percent of the U.S.’s locked up girls.

Vera will also focus on the jurisdictions that have the lowest numbers of girls in juvenile halls and camps, and that can “get to zero” with just a few tweaks to their systems.

Additionally, the initiative will include a new “Ending Girls’ Incarceration Innovation Network,” which will lead to the creation of gender-responsive pilot programs meant to divert more girls from justice system-involvement by tackling “some of the most intractable problems” contributing to the continued incarceration of girls.

“The girls who remain in the nation’s juvenile justice systems,” Vera says, “do not belong there.”