EDITOR’S NOTE: This story by Daniel Heimpel about a former foster child named Heather Matheson, is the first of a series of stories exploring the good and the harm done by a strategy called out-of-county placement that is used by the various county agencies in California’s foster care system. The story was co-produced by WitnessLA & the Chronicle of Social Change, of which Heimpel is the founder and executive director.

OUT OF COUNTY, CA: THE PROBLEMS WITH GOING THE DISTANCE

What is the cost/benefit ratio of putting foster children—who have already lost so much—into “out-of-county” placement?

by Daniel Heimpel

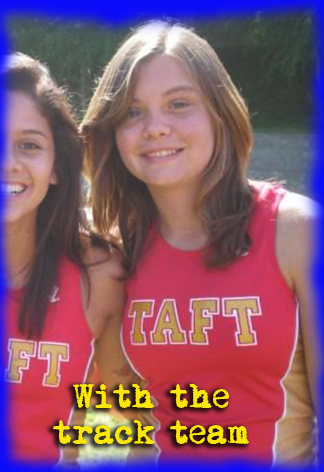

Heather, slight and precocious, made her Los Angeles County high school’s track team as a freshman.

It was a major feat, something to be proud of in the maelstrom of the 14 year-old’s life. Only months before, the county’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) had removed Heather from her home after a harrowing week of physical abuse and domestic violence.

After 15 months in what had been a promising foster-care placement near Taft High School, set in a pleasant part of the San Fernando Valley, things had started to fall apart. The department decided to move her in with relatives in neighboring Ventura County.

The only problem, one that seemed deceptively small in the context of her painful family history, was that she now had to take three buses to get to school, the only real support system she had left.

“Looking back on it,” Heather says, “it was this short period of time, but it was really stressful. It was a stressful year of life. I could have been going to school dances and football games, but I didn’t because the buses don’t run that late.”

In 2009, when Heather was put into what is called an out-of-county placement, California’s feudal foster care system was larger than it is today, with roughly 70,000 kids in the state’s care who had been removed from their parent’s custody and then placed with foster parents, in group homes or with extended family.

Yet, what hasn’t changed in the eight years since Heather began her foster care odyssey is the fact that 1 in 5 California foster youth will find themselves taken away from the county where they lived and placed in another county. At present, a total of 12,626—or 20 percent of all California children and youth in a foster care placement—live in a different county than the one that they previously called home.

The reasons why foster children and youth are forced to cross county lines so often boils down to conflicting goals within the system, simple geography, and the push and pull of housing costs.

One way to understand the out-of-county issue is to look at the different types of placements to which children are sent. In April, the Center for Social Services Research (CSSR) at the University of California, Berkeley, drawing data from California’s 58 counties, reported that there were 62,915 children in foster care, a number that has been steadily rising since a low point of around 55,000 in 2011. The main placement types for children are with kin, in privately run foster family agencies (FFA), in county-run foster homes and, finally, in group homes, which generally get the older and harder-to-place youth.

Data pulled from CSSR’s California Child Welfare Indicators Project shows that in 2015, 21 percent of kin (such as extended family members), 24 percent of FFA, 5 percent of county foster care and a whopping 36 percent of group home placements were out-of-county.

When it comes to kin—-the preferable foster care placement according to many child welfare leaders-—the reason why 21 percent of kids cross county borders has a lot to do with simple geography. If you live in L.A. County, but your aunt and uncle live in Ventura County, as was true for Heather, you’ll be placed in Ventura County since, all things being equal, that’s a better solution than asking you to live with strangers in L.A.

For children in FFA placements, the movement is, in part, due to the fact that privately run foster family agencies often span more than one county, and some of those counties do a better job at recruiting foster parents than others. So if the agency can’t find a child a foster home out of their list in one county, they’ll bounce them to a neighboring county.

When it comes to group homes, the cost of doing business is cheaper in suburban and exurban areas than the city centers where many high-needs youth come from. In addition, political pressure to reduce reliance on group homes has been felt most by the urban counties where anti-group home sentiment has taken deepest root. This means that in counties like Alameda and San Francisco, some group homes have been shuttered. As a result, the only place to send the kids who need to be in these higher-level placements is out of county.

The implications for children’s lives can range from the good, where foster youth are placed with family members who welcome and care about them, to the bad, where contact and eventual reunification with biological parents becomes strained by distance, and access to critical mental health services, and other services that the child needs, is often delayed or degraded, if ever delivered.

Carroll Schroeder, executive director of the California Alliance for Children and Family Services, sympathizes with the limited choices court officers and caseworkers often have to work with when placing foster kids.

“They have to make these kinds of Solomonic decisions all the time, and they have to do it at 4:00 p.m. on a Friday,” Schroeder said.

IN COUNTY

Heather’s case fell into the part good, part bad category.

Her journey began on March 5, 2007. That was the day that DCFS took the 13 year-old from her parents.

The official status review report submitted six months later to the county’s juvenile dependency court described the details of the situation. On that day, “and on numerous prior occasions, the child Heather Matheson’s mother, [redacted], and father, [redacted], have engaged in violent altercations in the presence of the child including father chasing mother in his vehicle… Additionally, father got the child involved in the parent’s arguments by requiring the child to call the mother on father’s behalf.”

What the report neglects to describe is the run-up to her removal. A week before Heather’s father chased her mother in the car, Heather showed up to John A. Sutter Middle School in Winnetka with bruises on her arms, prompting her teacher, who was also her track coach, to report child abuse to DCFS. When a social worker showed up at her parents’ door to investigate, Heather says she was too scared to say anything in front of her father, whom she remembers as being “short fused.”

After the social workers left, Heather’s father flew into a rage. Her mother, who was planning to move to Idaho with a new man, was not at the house.

“He wanted her to come over,” Heather says.

The girl’s father had a gun in his hand, and told Heather to call her mother.

“When I made a big deal that I didn’t want to do that, he hit me with the gun,” Heather says.

The blow knocked the 90-lb. 13 year old unconscious. When Heather came to, she made the call.

“I said, ‘I am scared, Dad has a gun and I don’t want to be there,’” Heather recalls saying.

But she got no help from her mom.

“If you want to live with him, you have to learn how to deal with him. It’s not my problem,” Heather recalls her mother saying.

Heather’s father then forced her into the car, leaving the gun on the dashboard. As he drove wildly from street to street looking for his wife at every motel he could find, Heather remembers watching the gun slide back and forth in front of her.

When the DCFS investigator who had visited Heather’s home days before showed up at school the next day for a scheduled interview with Heather, the frightened girl told the social worker the whole story. After hearing her out, the investigator told Heather she would have to take her to an emergency shelter. At this point Heather’s teacher, who was also in the room, broke in.

“I don’t want her to end up with strangers,” Heather recalls the woman saying. “My husband and I can take her in.”

Despite the teacher’s initial good will, the placement would not last.

OUT OF COUNTY

Court reports describe briefly why the placement with the Taft High School teacher failed.

“Rather than encouraging and edifying her for her A’s and B’s in school, they required A+ marks and pressured Heather,” the report reads.

Heather’s last days in her Taft High School teacher’s home were particularly strained. Heather remembers spending an awkward, scary and painful hour in the car with her teacher-turned-foster mother, as they drove from Woodland Hills to a DCFS substation in Santa Clarita.

Heather was heading to Santa Clarita to take part in a “Team Decision Meeting,” which typically features social workers and family members sitting around a table, trying to ascertain what is best for the child. At Heather’s meeting, her paternal grandfather, Donald Sr., sat alongside her uncle, Donald Jr., and his wife Gail. Heather’s father was there as well. Of the group of 10, Heather was the only kid in the room.

“How I understood the situation was I was going to this meeting to decide where I was gonna be placed,” Heather says. “I pretty much had three options. I could live with my grandma and grandpa, I could live with [aunt and uncle] Don and Gail or I could be placed randomly into a foster home. Each of those came with their own shit bag.”

The “team” determined that the aunt and uncle’s home was the best of the three options, never mind that they lived in Simi Valley, which was in Ventura County and more than 20 miles from her school, the one thing that felt solid to Heather in an otherwise unstable world.

“When it comes to movement, it is obviously one of the biggest banes of child welfare in the U.S. Period,” said Michael Nash, a juvenile court judge who until this year presided over L.A. County’s sprawling juvenile dependency system. “Agencies don’t place kids, they put them some place.”

The move to her aunt and uncle’s house was supposed to be temporary. The idea was that, as soon as Heather’s father could find a regular job, he would move out of his parents’ Canoga Park home (where he had been living since Heather had been removed and his wife had ensconced herself in Idaho), so that Heather could move in, and be closer to school.

While Heather’s dad successfully completed a year of anger management classes, thus arguably demonstrating his desire to re-unify with his daughter, he never got out of his parents’ house.

“The first week I was living at Don and Gail’s he would call and say he was looking for a halfway house, and he was really for it,” Heather says. “Then the calls stopped. He stopped updating us. It wasn’t really that shocking.”

In September, Gail and Don submitted their “caregiver information form” to the court. In the space where he was to report Heather’s “adjustment to [her] living arrangement,” Don scribbled in the following: “She seems to be happy hear [sic]. She would rather live at her grandparents (near her school + friends) but does not want dad to live there if she would move back.” Toward the bottom of the page, Don wrote, “Heather is welcome to live with us indefinitely.”

But there were structural problems built into the placement, says Heather’s social worker Christina Lee. Most glaringly, Don and Gail were ineligible for the same amount of money that a non-relative foster care placement would have gotten for taking Heather in. Instead they had to rely on the CalWORKS welfare program to try to bridge the fiscal gap, which paid a very low rate in Ventura County.

“At the time gas prices were ridiculous,” Lee said in an interview, and the monthly payments couldn’t even cover that cost.

As the weeks turned to months and longer, the need to drive Heather the long distances to get to her therapist, to high school and to her track meets took its toll on Gail and Don. Most days of the week, Don or Gail would give Heather a ride to Simi Valley family friends whose children also attended Taft High. But the friends’ kids’ after-school schedules didn’t always match Heather’s, meaning that she was often stuck taking three buses, and spending anywhere from one to three hours getting home.

“I would go to track and cross country and be totally beat and have a 40-minute drive home, or longer if I was on the bus,” Heather says. “Most people just went and ate dinner right after.”

While Heather appeared on the exterior to handle the move well, internally was another matter. The long bus rides and disappointment with a father who couldn’t or wouldn’t turn his life around, and a mother apparently unwilling to even try, had a corrosive effect. Heather had disturbing nightmares and began cutting herself.

Still, she was a strong girl, and that same period was also a time of school success, and ultimately became a crucible that would leave Heather with an independence and tenacity not often matched by her peers at San Francisco State University, where she is now nearing graduation. But those victories were still in the future.

As time passed, beyond the inconvenience, there were other consequences of being placed out of county.

For instance, Heather had difficulty accessing services meant to help foster youth transition into adulthood.

The federal government offers states money to provide independent living services to foster kids when they hit age 16. Typically, these are classes that teach foster youth how to set up a bank account, budget and cook. But unlike Ventura County, which took this federal mandate verbatim, Los Angeles County, which is often ahead of the curve on what it offers transition-aged youth, started its independent living program at age 14.

Because she was out of county, Heather didn’t take the classes until she was 17 and back in L.A. While she didn’t particularly enjoy them, she says they taught her how to “do a resume” and how to write a check.

“Those helped me for college. No one else had ever taught me that.”

Another disparity in services hinged on Heather’s mental health.

When she first came into foster care, she had been diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, an issue Heather worked on with Bridgette Walg, a therapist with a now closed children’s clinic located 20 traffic-choked miles from Heather’s Simi Valley address in Ventura County. As her time with Don and Gail ground on, Heather said that they became increasingly unwilling to drive her to her sessions.

While Walg couldn’t discuss Heather’s case, she talked generally about the importance of regular face-to-face meetings.

“If you want to take a kid to a different county, the foster parent should make a commitment to take them to their original therapists,” Walg said.

Heather fought hard to make as many appointments as possible. Yet her experience, wherein an out-of-county kid gets less in terms of mental health services, is common statewide.

A 2011 report from the Child Welfare Council, a working group comprised of the heads of the California’s major child-serving agencies, describes the lengthy delays and difficulties in accessing mental health services that out-of-county youth often encounter in their new county of residence. In California that year, out-of-county youth like Heather received 20 percent fewer mental health services on a monthly basis than their peers with in-county placements.

According to mental health advocate Patrick Gardner, founder of Young Minds Advocacy Project, the failure of the state to create an effective mental health system to support out-of-county foster youth dates back nearly 20 years.

Each county’s mental health department functions as its own HMO that often leaves foster youth from other counties waiting for critical services, he says.

“This is the number one issue that we get calls about, and has been for years,” Gardner says. “The kids that go out of county often have bigger problems, that are more acute, and they get less services because they’re essentially out of network. This isn’t a hidden population that you can’t find. They’re everywhere.”

Despite missing sessions, Heather, strong-willed, with a hard-won sense of her self-worth, made progress. The nightmares about her parents started to subside, and she stopped cutting herself.

“Despite having to dwell in another county,” social worker Lee wrote in her May 2009 status review, “Heather has adjusted well and is still able to thrive academically, preserve social relationships, and have a relatively positive outlook given her circumstances. Heather continues to excel on her school Varsity Track and Cross County teams and does her best to cope with the strained relationships she has with both mother and father.”

Charles Inada has been an attorney representing foster youth with the Children’s Law Center of California for nine years. Right now he is fighting through a crush of about 280 cases, and a few years back, Heather was one of his clients. Despite the dizzying numbers of children he comes into contact with, he remembers Heather distinctly. In his experience, out-of-county placements go either wrong or right, largely based on the quality of the social worker.

“If you get a good social worker, it is a lot smoother,” Inada said.

Heather says that her social worker, Christina Lee, never missed a meeting, even if it meant a long drive.

But even that point of security was all about to change. Lee was about to take a new job in the department, and Heather’s out-of-county placement was about to fall apart, sending her off to what she calls a “terrible” foster home.

SCHOOL DANCES AND FOOTBALL GAMES

In the summer between her sophomore and junior years, Heather, now firmly planted as Taft High’s number two runner, left for the annual cross-country trip at Mammoth Mountain.

Before she left, she and Gail got into a fight. Gail told her that the living arrangement “wasn’t gonna work,” Heather says.

The day after she got back, social worker Lee showed up at the house for a meeting.

“It was an ambush,” Heather says.

“Christina said that there was an opening at a house in North Hollywood and I could still go to my school and take the bus,” Heather says. “I think I was out by the end of the week.”

Looking back, Lee says that the placement was the best choice in a very limited pool.

“There is just not an availability of homes in the San Fernando Valley,” Lee said in an interview. “The need is greater than the supply.”

Heather’s next stop was a six-girl foster home. Heather says that the cereal boxes were filled with bugs and that the woman who owned the house would lock the girls out of the kitchen at night.

In October she told a school friend, Jake Linhardt, about what she had been living through. He told his parents.

“His family was, like, screw that,” Heather says. “We have an extra room.”

Heather lived with the Linhardts for the rest of her junior year, and through the whole of her senior year until graduation.

She made up for lost time, going to two proms, two winter formals and every single football game.

Meiling Bedard, Maria Akhter and Jeremy Loudenback contributed to this story.

Heather Matheson has worked for Fostering Media Connections, the parent organization of The Chronicle of Social Change, for nearly two years. She will graduate from San Francisco State University in the spring of 2016.

The best way to protect yourself and your children from the horrors of DCFS is to never speak to them in the first place. I have been a foster parent and have adopted three children from Los Angeles County DCFS. Even with that, they traumatized my six children when they stormed my home with armed deputies based on a false anonymous allegation to the DCFS hot line (it was later proven to be by one of the birth mothers and her Moranic friend). When I started posts such as this one to advise people of their rights, DCFS Directors Armand Montiel and Xiomara Flores – Holguin retaliated against me by directly contacting my employer in an effort to silence me. My advice to everyone everywhere is to never speak DCFS, never let them into your home, never let them see or speak to your children, never give them any information about your family, and never sign anything from DCFS. They can not legally enter your home without your consent, an emergency (such as a child screaming for help), or a warrant. Even with a warrant, you and your children can not be compelled to speak to DCFS; you should all continue to exercise your right to remain silent. If you think DCFS will return with a warrant, move or go on vacation. Most importantly, never become a foster parent.