The COVID-19-driven concern about the dangers inherent in congregate facilities like nursing homes, prisons, and jails, has also put a spotlight on similar dangers at juvenile halls, youth detention camps, and on California’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), with its four youth facilities, all of which have the potential to turn into contagion factories, should the coronavirus enter.

A new policy brief released Tuesday, by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ), about the state’s juvenile lockup system, points out that the new pandemic spotlight is also bringing into focus DJJ’s long-standing systemic shortcomings that, according to the report, make life dangerous — even without the threat of a pandemic — for the young people who wind up in the state’s system.

With a health crisis such as that which we are all living through, in the state’s youth prisons, things threaten to get worse.

“While adult prisons have largely dominated discussions regarding public health and incarceration in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic,” write the report’s co-authors, Renee Menart, and Maureen Washburn, “state leaders have largely overlooked youth who are currently housed in overcrowded, decaying, and unsanitary state-run institutions where they lack access to quality health care.”

And now, as of Monday, April 13, two staff members have been diagnosed with the virus at the two northern California DJJ facilities, O.H Close Youth Correctional Facility, and N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility, generally known as Chad.

DJJ is still under the umbrella of the state’s prison system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) — although Governor Newsom has committed to re-housing it under the Department of Health and Human Services. In the meantime, Menart and Washburn point out, reform in the state’s youth prisons are hampered by having no independent oversight.

The Office of the Inspector General does some oversight, which the OIG also does for the state’s prisons. But, write the authors, the OIG mostly investigates specifical allegations of misconduct by corrections staff members, rather than assessing and investigating how well or poorly things are going at the youth facilities by doing unannounced visits, and deep-dive reports on whether the youth lockups are still struggling with entrenched problems and patterns of neglect.

In February of 2019, CJCJ authors Menart and Washburn published a definitive and disturbing 101-page report on DJJ’s youth lockups, which described the multiplicity of ways the facilities were failing the young people whom they were supposed to be helping.

Now, with this new policy brief, they outline how little the destructive the problems they described more than a year ago have changed, including high levels of violence, poor health care, disconnection of the DJJ youth from their families, lack of strong rehabilitative programming, a discouragingly weak school system, and unsanitary conditions that, especially during this strange and challenging world of COVID-19, present serious health risks to both kids and staff.

Recidivism, suicidality, and violence

One of the best barometers of whether or not the DJJ facilities are helping the young people in the state’s care, is how well those young people do when they are returned to their communities. According to Menart and Washburn, the answer is not well. “DJJ fails to prevent most youth from returning to the criminal justice system,” the authors write. “Within three years of their release, 76 percent of youth are rearrested.”

(WitnessLA has an upcoming story about a promising new program, approved Tuesday by the LA County Board of Supervisors, and overseen by Impact Justice, that is designed to help the young people who emerge from DJJ to integrate successfully into their new lives.)

Another bad institutional success/failure barometer, the authors point to, is the DJJ system’s unusually high rate of attempted suicides in its facilities.

For example, from September 2018 through August 2019, DJJ reported 421 instances of suicidality, including eight suicide attempts. “Suicidality, which includes suicide attempts, intervention, watch, or prevention, is one of the most critical measures of mental well-being in a youth institution,” write Menart and Washburn.

Violence and uses of force

Another red flag highlighted in the new brief is the fact that staff use of force at DJJ often scores far higher than that reported in California’s adult prisons. From October 2018 to September 2019, administrators reported 535 such incidents, or approximately 1.5 per day, levels that the authors say “far exceed those reported in adult institutions.” In 2018, according to the report, youth in DJJ facilities were subjected to staff force at more than 18 times the rate of adults in state prisons.

In WitnessLA’s DJJ Watch series, Beto Guitierrez, one of our contributors who was at the time working at DJJ’s Chad as a teacher, described multiple incidents of kids being sprayed with pepper spray in a manner that went way past the point of using the OC spray to diffuse a fight or another kind of violent situation.

“I’ve seen youth who have been sprayed sit handcuffed for 20 to 30 minutes, sometimes as long as 40 minutes, before they are taken for decontamination,” he wrote.

Menart and Washburn acknowledge that the kids who are sent to DJJ facilities have higher needs and are generally there for more serious crimes. So they can be a challenging population.

In addition, much of the violence in DJJ is youth on youth.

Yet, DJJ’s violence stats are unusually high, as are the rates of injury, say the authors, along with “substandard medical care.”

In the one-year period from October 2018 to September 2019, they report, DJJ administrators reported 1,020 total injuries, or approximately 1.5 for every youth in the facilities. Nearly 60 percent of injuries were caused by other youth, and 5 percent required outside treatment.

Compared to young people confined in county youth camps and juvenile halls, youth at DJJ are “three times more likely to be referred for outside medical treatment,” say the authors, “which may reflect the severity of their injuries and ailments.”

For youth who remain in DJJ’s own medical system, things can be, in some ways, worse, write Menart and Washburn, who describe over-long wait times, misdiagnoses, and “frequent dismissal of serious symptoms.”

So what to do?

Well, one piece of good news on the DJJ/COVID-19 front is that, although the youth in the four facilities can no longer have in-person visits from their families, due to COVID-19 fears, “video visitation” is now reportedly available for DJJ youth “and their approved visitors.”

On March 27, DJJ launched a trial program at the Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp in Amador County. On April 11, the remaining DJJ facilities in Stockton and Ventura were to have launched their own version using Skype for Business.

A list of most of DJJ’s other pandemic precautions is harder to come by.

(We have an upcoming column from a WLA contributor that may have some answers.)

At the end of last month, we published an essay by Washburn, in which she outlined how the state could best protect its young residents during the current crisis.

Her main suggestion was the same as that of most youth advocates: DJJ needs to send as many kids home as public safety will allow. (Governor Newsom has already temporarily stopped the state’s counties from sending any more youth into the DJJ facilities for the duration of the crisis.)

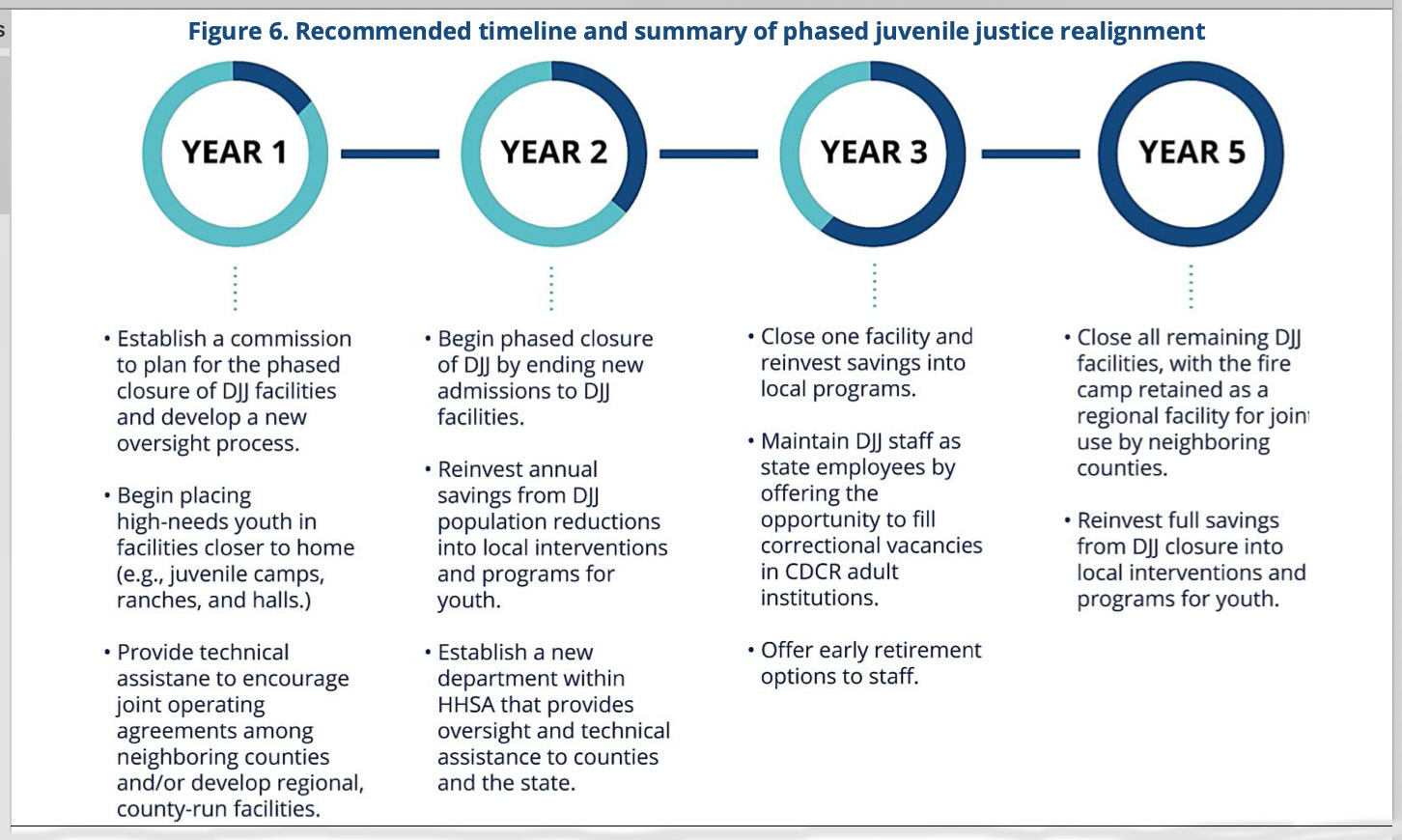

As for the solutions to DJJ’s deeper challenges, Washburn and Menart have outlined a five-year plan that would culminate in shutting down DJJ altogether.

(See below for the basics.)

“We don’t need to do it all at once, but it needs to start now,” Menart told us. “These ideas aren’t new.” she said. But most of all, right at the moment, “we’re just asking DJJ to hold itself responsible” for the youth in its care.”

Seems like a worthy suggestion.

Post Script

On Tuesday, April 14, Governor Newsom, signed an executive order that addresses one other part of the effect of COVID-19 on the DJJ facilities. The order calls for all discharge and reentry hearings to be held via videoconference to minimize the exposure of kids and other participants’ exposure to the virus.

The governor also shortened the process for youth to be considered for discharge by 30 days.

This new timeframe, by the way, does not impact victim notification, or whether victims will be able to participate in the videoconference hearings.

I hope they do close the facilities down because this has been going on for years I know youth that have been there. They’re not helping our youth they are actually hurting them more. Alot of youth have sick parents that can’t drive far distance and they suffer the most in those facility physically and mentally. I’m a witness to this. I’m a sick parent with a youth incarcerated and I don’t want my son to be sent to DJJ I had no idea what was going on there until I read this. I hope Newsom closes them and establish a program that keeps the youth close the home and family. That’s the only way to see a change in our youth is if they have all the support and resources to be productive in their futures to stay on the right path. Our youth is still our future no matter if they made a mistake.

Unfortunately for all of you the true story is not being told. DJJ staff provide the highest level of treatment nation wide. Staff deal with the worst juveniles in the nation and do so in a professional and caring manner. Treatment is provided in an individualized manner and with curriculum that has been proven to work. Maybe people should tour the facilities and speak to the experts rather than listening to people who have no idea what they are talking about. These folks should be commended for doing their job and walking he toughest beat in the state!!!!

I hear your cry I have known of alot of wrongs done to these young people I’m down ready to get a protest going so they can release our kids and grandkids Young lives matter