In Los Angeles County, court-ordered “community service” amounts to little more than coerced, unpaid labor, according to a scathing, first-of-its-kind report from the UCLA Labor Center and Noah Zatz a professor at the UCLA School of Law.

“The volume of mandatory community service is staggering in LA County,” said Lucero Herrera, the UCLA Labor Center’s senior research analyst.

More than 100,000 people in LA County register for community service each year, according to the report.

“We estimate that people perform about 8 million hours of unpaid and unprotected work each year,” Herrera said. During the millions of hours, those unpaid “volunteer” workers are not afforded the basic labor law protections against job site dangers, harassment, or discrimination.

Rather than the progressive alternative to incarceration and court fees that community service is portrayed as, it is, in reality, “a fundamentally coercive system situated at the intersection of mass incarceration and economic inequality, with the most profound effects on communities of color,” the report argues.

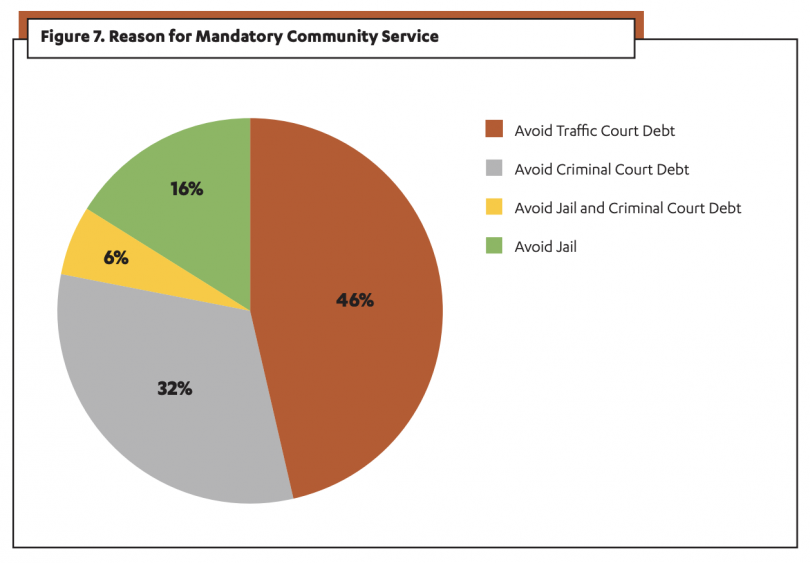

The UCLA team looked at 5,000 cases in which individuals were sentenced to community service between 2013 and 2014. They then gathered detailed information on 600 of those cases, and conducted dozens of interviews with those sentenced to community service, as well as public defenders, program administrators, worksite supervisors, and others.

What the report authors found as they investigated the use of court-ordered labor, was a system that operates largely unchecked — “outside the rules and beneath the standards designed to protect workers from mistreatment and exploitation.”

In this system, low-level violations, like littering, and traffic tickets, including fix-it tickets, lead to hefty court fees. While wealthy and even middle-class people can pay their fines with relative ease and wipe their hands of the whole business, low-income individuals are forced to complete community service when they can’t pay, or else face jail time and collections.

“It is difficult for people to complete their hours in addition to their regular employment and family responsibilities,” said Noah Zatz. “There is a lot of fear. Even people with traffic violations are anxious about being jailed for not completing their community service.”

In one of the cases cited within the report, a 33-year-old Latino man, identified as Mr. Rodriguez, was cited for littering trash and beer cans on a South LA sidewalk in 2013.

The man, with the help of an interpreter — but no lawyer — pleaded no contest to the charges. Rodriguez was hit with a base fine of $100, plus 8 hours of community service. With additional fees, he ultimately owed the court $520. After three years, that court debt had more than doubled, to $1,340, and was sent to collections.

Moreover, community service does not preclude individuals from having to pay court fines and fees, altogether. In fact, 40 percent of people accused of traffic violations, and 73 percent of people accused of criminal offenses, who took community service in order to avoid court debt still had to pay some money to the court — not to mention registration fees to volunteer work centers.

In one case, a 60-year-old woman who ran a red light was slapped with 68 hours of community service (the equivalent of more than a week and a half of full-time work), plus traffic school, and a $64 fine, all due in just over a month from her guilty plea.

While the woman, Ms. DeLeon, cleared all her required hours and paid her fine under the deadline, more than two-thirds of people from criminal court and two-fifths of people from traffic court did not finish their hours on time, according to the report. These missed deadlines had severe consequences, in many cases.

When people failed to complete their community service and were unable to pay the fines that community service was meant to wipe clean, they were often pushed deeper into the criminal justice system.

In criminal court, nearly one in five (19%) people experienced a probation violation, probation revocation, or a bench warrant for their arrest for failure to complete community service.

Among those cases involving traffic tickets, the most common penalty for failure to complete hours was that the court debt was sent to collections.

Community service sentences, the researchers found, often exacerbated financial hardship for people already struggling to provide for themselves and their families, because of disabilities, past convictions, family obligations, and lack of transportation, among other barriers.

The report offers recommendations for addressing the myriad failings of the community service model.

One of those recommendations is that community service could be “transformed into a jobs pipeline,” through which participants gain job skills and work for a real, fair wage. “The debt would be paid off through generally applicable wage garnishment practices that preserve enough income to meet basic needs,” the report suggests.

Court debts should also be subject to a cap determined by each individual’s ability to pay.

The county must also reduce over-policing, according to the report, especially with regard to traffic stops and searches in communities of color, and “quality of life” crimes like panhandling and littering through which low-income and homeless Angelenos are pushed into the criminal justice system.

Moreover, courts should replace forced labor with other alternatives to incarceration and court debt. And, if nothing else, community service systems should be reformed so that they follow labor standards, so that participants are treated with dignity and protected from hazardous conditions. Registration fees should be abolished, for one. “Workers should not have to pay to work for free,” at jobs that reduce opportunities for all paid workers, the report states.

“It is important to recognize that court-ordered community service actually undermines the security of all workers — not just the so-called volunteers,” said Tia Koonse, the UCLA Labor Center’s legal and policy research manager. “This system replaces what could be decently paid, unionized jobs with free, unprotected labor.”

You have got to be kidding.

I wonder if during their interviews with Mr. Rodriguez and Ms. DeLeon were they ever asked if they have had any other tickets or community service for the same violations? I can guarantee you the answer would be no.

Objective completed.

Taylor, serious question, I see the term “mass incarceration” used widely & it seems to have evolved into a multidimensional reference relative to justice system perceived inequity based in race, type of offense( drug, theft, community wellness issues; panhandling, tagging, etc). I read that there are 2.3 million people in jail & or prison in the US. That represents about 6/10 of one percent of the US population which is still a large number but not “mass” statistically. If you consider the editing/distilling( release/probation) that has gone on in the last decade the “mass” reference seems pretty thin. So would you put your experienced thought into what you think it means.