What kind of power does a civilian commission need if it is to effectively oversee a large, complex governmental department, which is also a law enforcement organization?

This question was the primary topic of discussion on Thursday, October 26, when the Los Angeles County Probation Reform and Implementation Team-–or PRIT, as it is known for short—met in front of a crowd of community members, lawyers, youth advocates, and others on the third floor of the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration.

The PRIT, for those unfamiliar, is a temporary nine-person body that is tasked with creating a detailed plan for the formation of the Probation Oversight Commission (POC), the new county government entity, which will oversee and advise the county’s probation department, and will report directly to the board of supervisors.

(If you’d like additional background on the proposed POC and on the PRIT read our stories here and here.)

During the previous PRIT meeting, the team members, plus various guests—along with community members and youth advocates in the audience who ventured to the mic to ask questions—discussed the mission of the new commission.

This day, however, was devoted to the thorny issue of what powers everyone thought the POC ought to have, and how those wishes squared what powers it could legally possess.

Most significant among the powers up for discussion was subpoena power.

To put that particular power in context, it helps to know which other county oversight entities have it, and which do not.

For instance, the Office of the Inspector General, which oversees the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, and has investigative power, does not have subpoena power.

The Civilian Oversight Commission—or COC—for the LA Sheriff’s Department, on which the new POC is supposed to be generally modeled, does not have subpoena power either—although when the body was formed, many advocates and community groups argued strenuously that the COC needed it.

That argument has never gone away. In fact, a county ballet initiative that will be placed on the 2020 ballot, if passed by county residents, could give the commission the elusive ability.

The present LA County Probation Commission assuredly doesn’t have subpoena power. In fact, it frequently has trouble getting any kind of serious data and/or documents out of the probation department, even when the information is something any journalist can acquire, at least in theory, through a California Public Records Act request.

The LA Police Commission, which oversees the Los Angeles Police Department, has it, but they are an outlier.

With all of the above in mind, the idea that the soon-to-be-created LA County Probation Oversight Commission—or POC—could have subpoena power, has been deemed by many to be pretty much off the table.

But then about 30 minutes into last Thursday’s meeting, this no-subpoena-power conclusion unexpectedly became less solid than it had formerly appeared to be.

Limits and more limits

To help jump-start the conversation about what powers the new commission ought or ought not to have, PRIT’s chairperson, Saul Sarabia, had lined up a list of “informational witnesses” to explore the issue.

Among the first of these witnesses was Rod Castro-Silva, a senior attorney from Los Angeles County Counsel, which provides legal advice to the board of supervisors, and other county departments.

Castro-Silva presented a crisp outline of some of the legal restrictions that will circumscribe the POC’s actions.

To begin with, he said, the POC will be a Brown Act body, which means all its meetings must be open to the public, thus it cannot meet privately.

(In short, the state’s Brown Act, is an act of the California State Legislature, passed in 1953 and authored by Assemblymember Ralph M. Brown, which guarantees the public’s right to attend and participate in meetings of local legislative bodies.)

In addition, because of its Brown Act designation, the commission will be prohibited from getting any documents that can’t also be requested through the Public Records Act (PRA), since everything it does, as previously delineated, pretty much has to be public.

For example, most all of the files pertaining to the young people under juvenile probation’s care would be prohibited to the new POC, because the files of juveniles cannot be made public. Many court files for adult probationers would also be prohibited.

In addition, the new POC could not obtain personnel files of the department’s probation officers, as they are peace officers and thus most of this information would fall under the protection of the Peace Officer’s Bill of Rights.

(That last prohibition has been modified slightly, Castro-Silva noted, by two the newly signed laws, SB 1421 which allows public access to personnel records in certain instances, such those involving officer shootings and other major force incidents, along with confirmed cases of sexual assault and lying while on duty. AB 748 requires all law enforcement agencies in California to release body cam footage from critical incidents within 45 days. But as most probation officers don’t carry guns or have body cams, neither new law will apply in most cases.)

To get around some of the Brown Act restrictions, the new commission could use the Office of the Inspector General as its investigative arm, in that the OIG can get some of these prohibited documents, since it isn’t a Brown Act body.

After Castro-Silva had wrapped up his presentation, PRIT team member Cyn Yamashiro asked if some of the prohibited documents and/or information, if subpoenaed, “could be produced by a judge?”

Yamashiro is both a longtime juvenile defense attorney, and a member of the vexingly power-free existing probation commission.

Castro-Silva said, yes, that was true. The Board of Supervisors has subpoena power, so they could request such material. But subpoenas “can be challenged,” he said.

What he did not add—what he didn’t need to add–was that a body like the proposed probation oversight commission, as is true with the LASD’s oversight commission, likely cannot have subpoena power without a change in the applicable legal statute.

Game change

The next person to weigh in on the matter of the POC’s prospective powers, or lack thereof, was Patricia Soung, who is the director of youth justice at the Children’s Defense Fund, where she is also the staff attorney.

When she got up to speak, Soung stipulated that the analysis she was about to present was developed jointly with attorneys at the ACLU of Southern California, most specifically, it turned out, with ACLU staff attorney, Ian Kysel, who is known for his ability to excavate the exact right set of legal references or precedents for whatever predicament is at hand.

The issue of what powers that the commission should have, Soung began, is essential because the commission’s “efficacy flows from whatever powers we grant it to do its job.”

She then proceeded to unfurl a step-by-step lesson in the history the state’s juvenile justice system, beginning with the first juvenile court, which was established in 1903, and including the creation of county juvenile justice commissions, which have—ta-da!—subpoena power.

“In our analysis,” Soung said finally, “the governing law dictates that the oversight commission should have robust, expansive powers,”—including powers like “investigative power and subpoena power.”

Suddenly the audience members came to full attention.

Did she just say the POC should have subpoena power, and that it legally could have subpoena power?

Well, yes. She did.

Soung, who has a past as a juvenile defense attorney, and used to teach juvenile law and procedure at Loyola Law School, also ticked off a list of other relevant “powers” the POC ought to have, such as the power to inspect various probation facilities where kids reside, the power to review policy and budgets, the power to have access to independent counsel—and more.

A robust, independent and fair oversight mechanism, Soung continued, “must not depend on momentarily strong leadership, relationships, or good faith” in the department “for access to information, testimony, and records.” It must outlast leadership and relationships that can change over time.

“Subpoena power does not guarantee access to desired information, but it is a tool that we can exercise to take into account a balance of interest,” Soung said.

“It is not a matter of choice,” it is a matter of law.

“…State statute is explicit,” Soung concluded firmly.

There was more, like the fact that the law appears to apply to the juvenile side of probation oversight, not necessarily the adult. But Soung’s statement about the law was the bottom line of her presentation.

Alleged assaults of pregnant girls and bully pulpits

During the rest of the meeting, other informational witnesses made other relevant points.

Former Los Angeles juvenile court judge, and existing probation commission member, Jan Levine, told the PRIT team members that she was “familiar with serious problems within the probation department’s practices and facilities.”

Yet, she said, as a commissioner, she was “frequently frustrated by the structural impediments to the current commission’s ability to effect meaningful and lasting change” because the group was “significantly limited in the tools available to it.”

Levine brought up a recent example in which a fellow commissioner, Jacqueline Castor, visited Central Juvenile Hall and while there, was approached by a pregnant young female probationer who told her that the previous night she’d been pushed off a table by a probation staff member because she had not gone to her room when told to. The girl said she had been dragged to her room by two officers, and allegedly threatened with the use of pepper spray by staff on the way.

“Another girl who witnessed the incident corroborated the girl’s story,” said Levine.

Yet, when Castor and other commissioners asked for a report on the matter, probation higher ups along with county counsel told the commission that the alleged incident was a “personnel matter,” and therefore must remain confidential since the commission was a Brown Act body, and could not go into closed session.

For these and other reasons, Levine told the PRIT members, the new POC must be enabled “to go into closed session.” And, like Soung, she emphasized that, to be effective, it will need its own independent outside attorneys. And that it also needs “the power to subpoena witnesses.”

In a variation on Soung’s presentation, Levine told the panel that, based on her examination, the interpretation the old probation commission has repeatedly been given about state law prohibiting the commission from ever going into private session, “is contrary to the plain language of the statute, per a 2006 opinion from the State Legislative Counsel.”

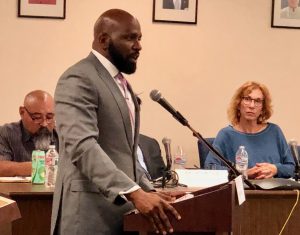

Attorney, Bryan Williams, who is the executive director of the Sheriff’s Civilian Oversight Commission, said that one of the biggest challenges of the COC “was finding out what power we had and what power we didn’t have.” Its greatest “greatest power,” they found, is the bully pulpit. “But we had to learn how to use it,” he said.

Max Huntsman, LA County’s Inspector General, told the group that when the OIG started in 2014, the LASD “refused to give us access” to the reports and information they needed for two years. “For two years the sheriff said, ‘no way,’ you get nothing!’

“You know when they gave us access?” Huntsman asked the room rhetorically. “They gave us access when the working group, a lot like the PRIT, started talking about subpoena power for the Civilian Oversight Commission.”

And so it went.

There were other speakers, like Mark Smith, the Inspector General for the LAPD, and other pithy points.

Yet, by meeting’s end, one thing appeared to be clear: subpoena power was no longer off the table.

It was now on.