The primary power in both our American justice system in general, and in California’s justice system specifically, does not lie with the judiciary. Nor does it rest with police. The most powerful, and in many ways least accountable, individuals working in our nation’s system of justice are our prosecutors.

In his essay for the Georgetown law Journal about the nation’s most pressing criminal justice reforms, Judge Alex Kozinski of the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, writes about how prosecutors do not have to fear sanctions.

Defense lawyers who are found to have been ineffective regularly find their names plastered into judicial opinions, yet judges seem strangely reluctant to name names when it comes to misbehaving prosecutors. Indeed, judges seem reluctant to even suspect prosecutors of improper behavior, as if they were somehow beyond suspicion….Naming names and taking prosecutors to task for misbehavior can have magical qualities in assuring compliance with constitutional rights.

If judges have reason to believe that witnesses, especially police officers or government informants, testify falsely, they must refer the matter for prosecution. If they become aware of widespread misconduct in the investigation and prosecution of criminal cases, a referral to the U.S. Department of Justice for a civil rights violation might well be appropriate.

As a group, both statewide and nationally, prosecutors defend their positions energetically, often acting as the main lobbying group against criminal justice reform—as was the case two weeks ago when President Barack Obama and a bipartisan alliance in Congress called for federal sentencing reform. In response, the National Association of Assistant U.S. Attorneys labeled such proposed changes “a huge mistake,” and—incredibly—called for more prisons.

So who are these prosecutors?

After all, we have a fairly accurate idea of the gender and racial make-up of our police and sheriff’s departments. We also have those same stats for our teachers and for our elected officials. But when it comes to prosecutors, the same demographic of information has not been made public.

As a consequence, critics observed, there has been no push to diversify, because there was no way to know whether or not prosecutors were at all representative of the communities they serve.

Recently, however, all that has begun to change. And the resultant news, according to researchers, is not cheering.

Earlier this month, we reported on a study by the Women’s Donor Network, which examined the racial and gender breakdown of elected prosecutors nationwide. The report—Justice for All?-–found that, of 2,437 elected prosecutors in the U.S., 95% are white and 79% are white men. A startling 60% of states have no elected black prosecutors. Only 17% of elected prosecutors nationwide are women.

Now, a group of Stanford Law School students, working with The Stanford Criminal Justice Center, has drilled down into state figures to make demographics of California prosecutors available for the first time. The team gathered numbers from prosecutors’ offices in 52 of California’s 58 counties, representing nearly 98 percent of the state’s population, and found that whites, who comprise slightly more than 38 percent of the state’s population, hold nearly 70 percent of prosecutors’ jobs.

“The last time 70 percent of Californians were white was four decades ago,” noted the report’s authors. California prosecutors, the report concludes, are “Stuck in the ‘70s.”

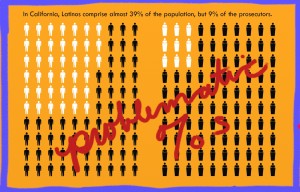

The new report, which is actually titled Stuck in the ’70’s: The Demographics of California Prosecutors, found that Latinos are the most poorly represented among prosecutors. Latinos represent almost 39 percent of the population in California but make up only 9 percent of California prosecutors.

The data collected also showed that women are underrepresented in the supervisory ranks of prosecutors in California. Forty-eight percent of California prosecutors are female, but 41 percent of prosecutors with supervisory titles are women.

In an op-ed for the Los Angeles Time, Debbie Mukamal, the executive director of the Stanford center, and Stanford Law School professor David Alan Sklansky, the center’s co-director along with Petersilia, explain why this outsized lack of diversity needs to be addressed.

Here are a couple of clips:

In one police killing after another over the last year, as the nation has waited to find out if charges would be filed against officers, we’ve been reminded that prosecutors are in many ways the most powerful officials in the American criminal justice system.

Prosecutors decide whether to bring a case before a grand jury, how hard to press for an indictment, what charges to request and how punitive a sentence to recommend. Grand juries almost never refuse to file the charges prosecutors request. And mandatory sentencing laws often allow prosecutors to determine the penalty by picking the charges.

Moreover, the vast majority of criminal cases in the United States end in plea bargains, not in trials. So the discretion exercised in our justice system is mostly not by judges but by prosecutors, and typically not by elected district attorneys but by the legions of far less visible lawyers they employ.

[SNIP]There was some good news in what we found. African Americans are not underrepresented among California prosecutors, although that is partly because the number required to meet that mark is relatively low, given that blacks are just 6% of the state’s population. We also found that close to half of all California prosecutors — 48% — are female, although the figure drops to 41% in supervisory ranks. (Police departments are much worse when it comes to gender equity: Only 13% of law enforcement officers in California are female.)

Our study did not analyze how workforce diversity in prosecutors’ offices influences the outcome of criminal cases. But other researchers have found that when racial minorities are underrepresented among prosecutors, minority defendants receive stiffer sentences. And researchers have shown that respect for the law and trust in legal institutions are undermined when criminal justice agencies do not reflect the communities they serve….

The article notes that at both the County (District Attorney) and state levels (Attorney General) prosecutors are elected officials. If either one does anything egregiously wrong a Free Press is supposed to keep the electorate informed and corrective action can be taken at upcoming elections. That’s the way things are supposed to work, and I personally don’t think things should be modified to accommodate a change in the demographics due to illegal immigration.

According to the Guardian, in the case of approximately 53 million Latinos, seven million are undocumented immigrants, five million are legal immigrants who are not citizens and cannot vote, and 17 million are too young to vote (for now). That leaves an electorate of just 24 million, of which less than half votes, compared to around two-thirds of whites and African Americans. That doesn’t sound like a change in demographics accommodating illegal immigration…rather it’s a potential paradigm shift predicated on voter education, political maturity, and the dynamics of a changing electorate. Such as it is, this article is just a shot across the bow, awareness is often the precursor of change.

#2: “…Awareness is often the precursor of change.”

Change to what? A system of electing prosecutors by an informed electorate to…?

Chicago, New York, Baltimore, St Louis, and Los Angeles all have diverse Police Departments but still, according to some, do not enjoy the trust of minority communities. When Stanford Graduate students decide to study the breakdown of the family structure in minority communities and its impact on criminality, please give us a heads up! For now they will be studying something of substance as the why crime occurs at higher levels in some communities and not others.

Daylight sucks, doesn’t it?