Correctional officers are, by definition, on the front lines of any prison system.

If the prison environment is overcrowded, overly violent, dysfunctional, or in a multiplicity of other ways, unhealthy—which most American prisons have been, historically—the correctional officers cannot help but be affected.

That unhealthiness has measurable effects on the physical and emotional well-being of the correctional officers, which in turn affects the way they do their work, according to a new report released this week.

“Because of this,” said the authors of the study, “correctional programs and policies can have little chance of success without” a focus on the overall health of correction officers.

Lead researcher, Dr. Amy Lerman, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley (Photo courtesy of the Institute of Governmental Studies)

The impetus for the new report first came about when the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA), the CCPOA Benefit Trust Fund, and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, joined forces with researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, to probe, analyze, and then to come up with programs to address the crucial issue of law enforcement’s health and wellness inside California’s prisons, a topic that, the report’s authors say, has been largely ignored by academic research.

The CCPOA began pushing hard for the study after discovering that the suicide rate for its members was 19.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2013.

As a starting point for the research, Dr. Amy E. Lerman and her team at U.C. Berkeley developed the California Correctional Officer Survey (CCOS). The idea was to gather information on the thoughts, attitudes, and experiences of criminal justice personnel.

In the spring of 2017, a 61-question version of the survey was conducted, which brought responses from 8,334 officers and other sworn staff statewide.

This sampling, said Lerman, provides “a vast cross-section of officers across all of California’s correctional institutions and parole offices.”

At WitnessLA we have been waiting for the outcomes from this first-of-its-kind survey of California’s corrections officers.

Now we have seen the report, and its findings are sobering.

Exposure to violence and its consequences

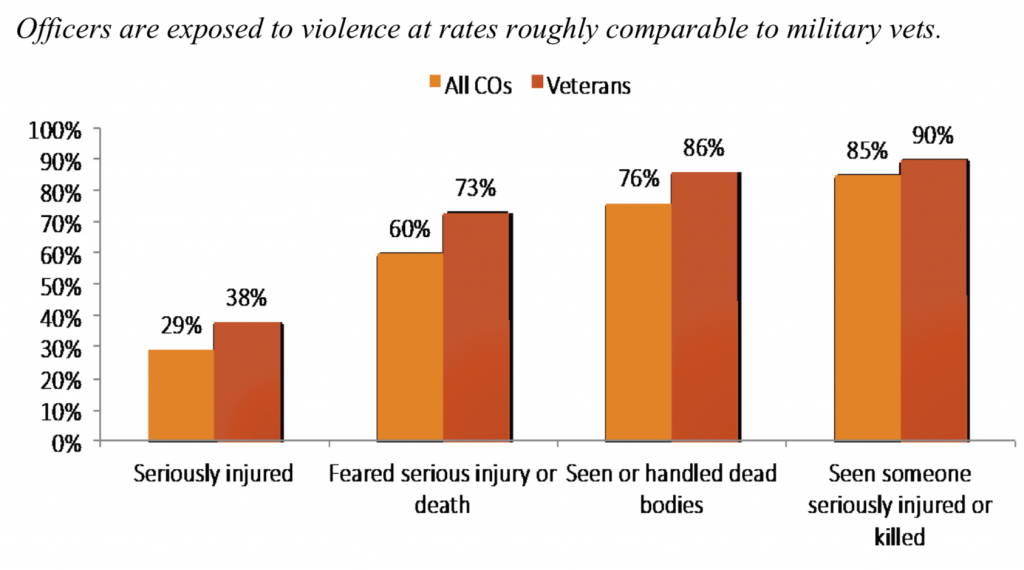

Among the report’s main findings is the fact that California correctional officers are exposed to violence at very high levels. More than half of correctional officers reported that violent incidents are a regular occurrence at the prison where they work.

Moreover, 80 percent of those surveyed told researchers that they have responded to at least one violent incident in the last six months, and 10 percent report they have been seriously injured while responding to these incidents. In total, 17 percent of correctional officers report they have been seriously injured on the job, 48 percent have feared they would be injured, 63 percent have seen or handled dead bodies at work, and 73 percent have seen someone seriously hurt or killed while on the job.

Moreover, 80 percent of those surveyed told researchers that they have responded to at least one violent incident in the last six months, and 10 percent report they have been seriously injured while responding to these incidents. In total, 17 percent of correctional officers report they have been seriously injured on the job, 48 percent have feared they would be injured, 63 percent have seen or handled dead bodies at work, and 73 percent have seen someone seriously hurt or killed while on the job.

Not surprisingly, this over-exposure to violence produces a list of consequences for officers, both physical and emotional.

For example, 50 percent of the officers surveyed said they rarely feel safe at work.

Additionally, around 1/3 of California corrections officers said they were dissatisfied with both the availability and the quality of safety equipment. And 70 percent of officers didn’t think there were adequate staffing levels to provide for the safety and security of those who work in their facility

We know from past research into the effects of trauma, that the condition of feeling chronically unsafe, typically produces adverse effects on an individual’s physical and emotional health. So it was with the state’s corrections officers. The survey found that those COs who didn’t feel safe at work were more likely to report headaches, digestive issues, high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease, than those who did not experience chronic feelings of being unsafe during their work shifts.

Those who felt less safe were also likely to rarely feel rested, even when they got extra sleep.

Specifically, 39 percent of all officers and 47 percent of those who felt unsafe at work reported feeling chronically exhausted even after sleeping.

PTSD, nightmares, depression, and thoughts of suicide

In addition, the researchers found, the stress of the job produced a high incidence of depression among the officers surveyed.

More than one-third of the officers reported that someone in their lives had told them they have become more anxious or depressed since they started working in corrections. Twenty-eight percent reported often or sometimes feeling down, depressed or hopeless, and 38 percent said they have “little interest or pleasure in doing things,” according to the report.

Similarly, one in three had experienced at least one symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder. Moreover, 40 percent of officers reported that they have experienced an event so frightening, horrible, or upsetting at work that they have had nightmares about it.

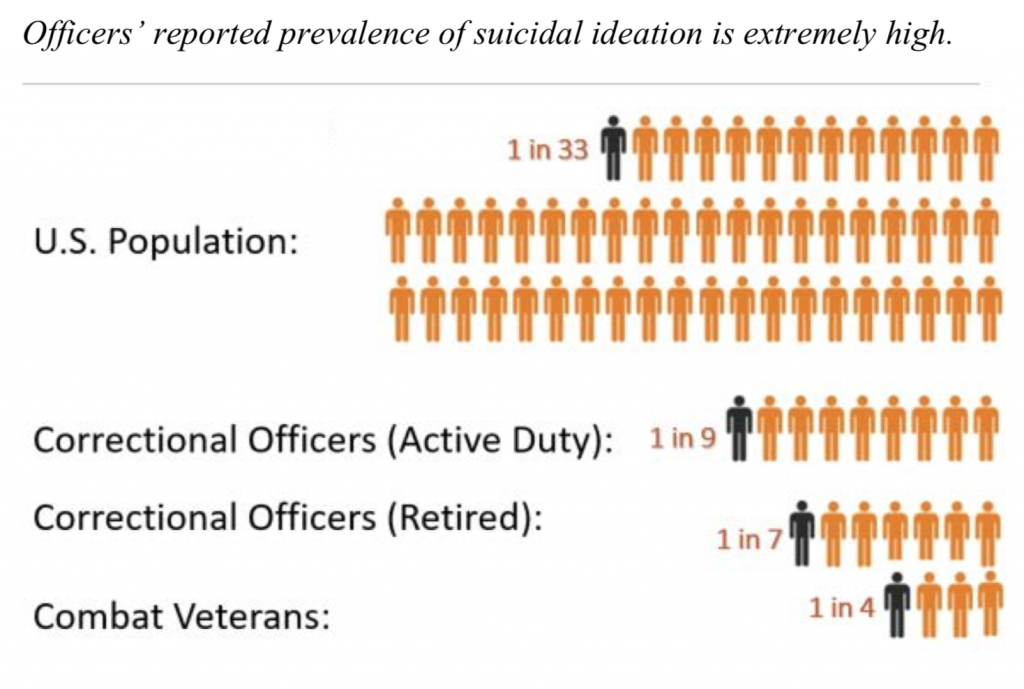

Ten percent of correctional officers said they had thought about killing themselves.

It is particularly concerning that the rate of suicidal thoughts was even higher for retired correctional officers (1 in 7) than it was for active duty officers, whose rate was already high (1 in 9). Plus, of those who said they have thought about suicide, 31 percent reported thinking about it often or sometimes in the past year.

More than 7 in 10 hadn’t told anyone about their suicidal thoughts, meaning that most are suffering silently and alone.

Officers want help with their trauma and stress

The stress the COs deal with as a consequence of their work was exacerbated by the fact that, according to the report, few felt that they were getting the help they need to handle the harmful collateral effects of their jobs.

For instance, officers reported that they have either not been trained at all on health-related issues, or that the training they’ve gotten isn’t much good. One-third reported that training they have received related to stress management and dealing with trauma has been of very poor quality.

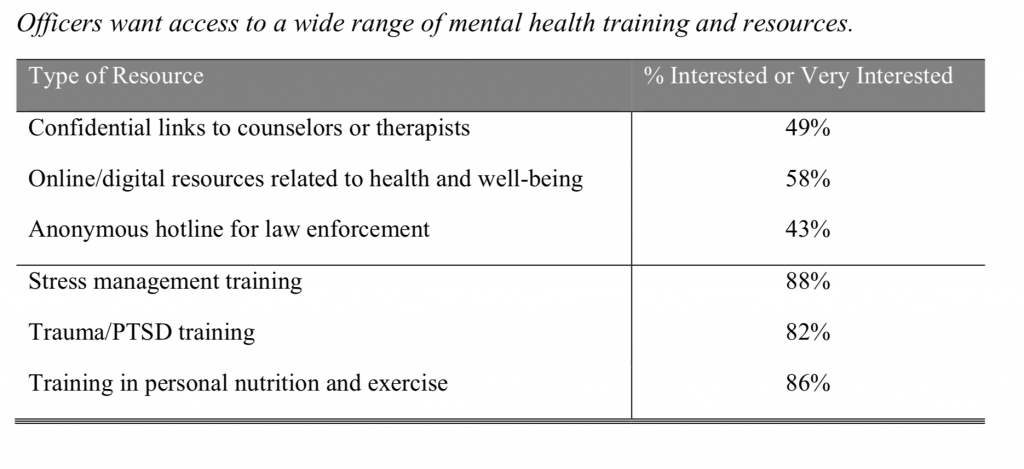

And nearly all of the COs surveyed reported that they really did want help, but that it needed to be the right kind of help.

When asked what kind of help or training they wished they had, nearly half, or 49 percent, said they wanted confidential links to counselors or therapists. (The confidentiality issue was very important, as officers feared being stigmatized.) Similarly, nearly 60 percent would like an anonymous hotline to call.

Most of all, they wanted good training programs. For example, 82 percent wanted training in how to handle trauma and/or PTSD. Even more—86 percent—wanted instruction regarding how to to do better with nutrition and exercise. And, scoring highest, 88 percent said they needed training in handling stress.

In other words, California’s correctional officers want and need help, and we’re failing them.

The relationship between stress and fear—and workplace attitudes

Another important factor the report revealed was the finding that the stress affecting corrections officers’ physical health and emotions, also has an influence on the way they see their jobs.

For example, most correctional officers surveyed, “generally do not think they are making a positive difference,” when on the job.

Less than half agreed that they positively influence other people’s lives through their work, and the same proportion thought inmates are no better prepared to become law-abiding citizens when they leave prison than they were when they came in.

Furthermore, there was a strong correlation between officers’ work-related stress and their attitudes toward the purpose of their work, the survey found.

For example, officers with at least one symptom of PTSD were less likely to think rehabilitation should be a major goal of incarceration and more likely to think that the purpose of prison is solely for maintaining the safety of the public, not for improving the skills or behavior of those confined within its walls so they do better on the outside when they’re released..

Interestingly, a majority of officers nevertheless agreed that rehabilitation programs should be made available to those inmates who want them. Specifically, 77% supported vocational training, 86 percent supported drug and alcohol treatment, and 82% of respondents supported academic training up to and including GED preparation.

“Historically, it’s been hard to get attention to mental health issues among law enforcement,” project leader Lerman said. “There’s been just so little information out there about what people are experiencing, and how to successfully intervene.”

The fact that corrections officers are suffering on the job is not, of course, confined to California. Last year we ran a personal story about Oregon Department of Corrections sergeant Michael Van Patten, and his son, who followed his father into the business, and both were suffering.

But California is often viewed as a bellwether for trends in the corrections field, Lerman pointed out.

Thus, “as California begins to seriously address these issues,” she said, “we hope that the rest of the country will follow.”

Common CF….we’re on the edge of our seats waiting for your riveting and enlightening commentary on this story.

These fat, over weight, lazy, racist prison guards with their fat pensions are all just whiners….right?

Don’t let us down..

This study should also include those officers who work in local county jails and holding facilities.

A result of the short-sighted decision by a judge, enacted by the states legislature and “marketed to the people” as prison deform as a way to cure prison over-crowding and save money, AB 109 was born. Now these sane prisoners that were once the problem of CDC guards, having been pushed into county jails, are having the same effects at the local level on the officers charged to oversee them.

Of course these local facility workers aren’t being studied yet and the facility managers are either “unaware” of or don’t care about the mental and physical trauma their workers experience as well.

Time will only tell…

So at least into the 70’s didn’t graduates of the the Sheriff’s Academy serve their first two years at the County Jail? Always wondered about the effect that had on the new officers.

Now they can spend their entire careers there if they so choose.

…at least in the case of the LA County Sheriff’s Department.

Hmmm….

But if THAT gets too boring people can always go (?) here:

https://www.cbp.gov/careers/cbp-officer

That’s the U.S. Border Patrol but, according to the link,

1. The written exam is 4-6 hours long

2..The polygraph exam is likewise 4-6 hours long, and I have read reports that it has a 75% failure rate, a fact that can be Googled

3. Not in the link is the probability that Freeway Therapy in the Border Patrol would probably be a bitch.

Conspiracy, I am honored that you invite me to share my thoughts. I was under the impression that you were not too fond of me. I stand corrected, and am honored. So, let me share my thoughts. I imagine such a job is stressful. Its not for me and I have no interest, and fortunately no need, to do such a job. However, a few years ago the CDC published a study that looked at suicide rates by occupation. I do not know if they publish it regularly, but I would imagine you may be able to find it or its abstract on Google, Cognistator’s preferred research source. Although, I direct you to either the study or its abstract.

So, that study found that that there were quite a number of occupations with much higher suicide rates than police or correctional officers. Some of the professions with higher suicide rates are manual labor workers, such as miners, fishermen, lumberjacks. Also, farm workers, production line workers. Can you believe that? And, sit down, architects and engineers have higher suicide rates. Now, its hard to untangle cause and effect. I imagine some professions, like engineers, attract loners, who may be more susceptible to depression and therefore suicide. Being a corrections officer is, I must admit, a shitty job, and given the nature of the job it may have an adverse effect on one’s mental health. It may also be true that the job attracts people that may be more susceptible to depression and mental health issues. Its a shitty job, the person may not have many options (lack of control contributes to depression and suicide), and it may attract people with mental health issues, such as those that may have sadistic streaks or control issues.

Cause and effect is much longer conversation. What we can say is that there are many other occupations where the suicide rate is higher, like farm workers, but I don’t see you or ilk standing up for or showing concern for farm workers. So, I sympathize with those officers, but they get no pass when they beat up some poor schmuck in prison, as your ilk has been found to do on occasion. And, unlike the farmworker, the fisherman, the lumberjack, etc you get nice pay, great benefits, and as we learned, you can double dip into the trough and get great pay and pension at the same time, and then you can claim you have carpal tunnel and go on disability while collecting both and do some scuba diving. Don’t whine, you actually have it pretty good.

Cf, hey girly I’m thinking you ought to be more appreciative of the people doing the dirty work. As the great Richard Prior once said, “thank god we got prisons”. So the next time you’re trollin the bars looking for one of those big bad men you’re always rambling on about, maybe you can give a corrections officer a little attention, I’m sure we all agree it’s the least you can do, you know for society or whatever.

CDC Report 2016…

The highest female suicide rate was seen in the category that includes police, firefighters and corrections officers. The second-highest rate for women was in the legal profession.

There is not enough research on this subject or services. I have conducted an extensive scholarly search. I previously worked for the department of corrections in California for 10 years. I have done a social work internship at Prison in California working in mental health with incarcerated individuals and have experience on both ends. I am currently working on my Masters Degree in social work working on a project, I cannot find any research or programs that focus on assisting officers with PTSD or AOD problems nor their families that obtain a great amount of both physical and emotional abuse. I have family members that both work at the prisons and are retired from the prisons. I can tell you first hand that the jobs do provide for, but shatter families. I have seen suicides and threats. I could go on. There is a dire need for research on this subject. It is not just in California but all over. AS I am sure you understand.

Thank You