Is Governor Gavin Newsom doing enough to address the coronavirus threat to California’s prison system? Right now, the answer to that question is far from clear.

For weeks, calls for early prison releases by concerned justice advocates and attorneys have been left unanswered except for a single executive order to block the usual stream of new transfers from county jails to state prisons. The same block was put into place to temporarily stop the flow of youth transfers from county facilities to the Department of Juvenile Justice.

Yet, with more than 122,000 men and women in the 35 adult prisons run by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, temporarily stopping the river of incoming people from the state’s various county facilities (which have their own COVID-19 problems) is not a solution.

Even one of the CDCR’s former directors described the prison system he used to oversee as “a tinderbox of potential infection.”

On Friday, Governor Newsom made news with the announcement he had commuted the sentences of 21 California prisoners and issued 5 pardons. Yet, the governor’s office noted that this batch of clemency decisions was already “in progress before the COVID-19 crisis.”

In other words, the commutations and pardons the governor issued for 25 people were already set to happen, pandemic or no pandemic. Furthermore, many of those with commuted sentences are not guarantees of release. They will now need to go before the parole board — which has not been open for business for over a week. (The parole board is, however, slated to return with videoconference parole hearings by April 13, at the latest.)

Meanwhile, the state has had three confirmed cases of coronavirus within the prison population, as of March 29, and has tested 197 prisoners, so far, according to the department’s coronavirus tracker. Two of those people with positive tests are at California State Prison-Los Angeles County and one is inside California Institution for Men in Chino

Yet, to have tested only 197 people out of the more than 122,000 who are presently in the state’s facilities — thousands of whom are old and/or with compromised health already — is not exactly reassuring.

This is especially true in light of the fact that the number of prison staff members who have tested positive for the disease appears to be steadily growing, however. As of March 29, there were 17 confirmed cases of COVID-19 among prison employee ranks, up from 9 cases four days earlier.

Hoping for intervention

On Wednesday night, March 25, attorneys representing California prisoners asked a federal three-judge panel to intervene and force the state to further reduce overcrowding by releasing or relocating people convicted of non-violent crimes who are medically fragile or who are close to their release dates.

(The panel of judges has been engaged in oversight of the state’s prisons since 2009, when a federal court ordered California’s governor to address its prison overcrowding crisis, which was having a debilitating effect on the health of those inside the state’s prison facilities. The ruling was famously upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2011, which declared the state to be in violation of the 8th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.)

The recent emergency motion, filed by attorneys from Rosen Bien Galvan & Grunfeld, and the Prison Law Office, asks the judges to further reduce the prison population cap — which is now 137.5% of capacity — that the federal judges imposed in 2011.

“Now, more than five years after the State reached the numerical target of the overall population cap, it is indisputable that the cap is inadequate to permit the delivery of constitutional health care in the current crisis,” the motion states.

Tinderbox and petri dish

Speaking with KQED, Former CDCR Secretary Scott Kernan called the state’s prison system more of a “petri dish” than close-quarters cruise ships. The social distancing necessary to stem the spread of coronavirus is all but impossible in prison.

Image: California Institution for Men, 2019

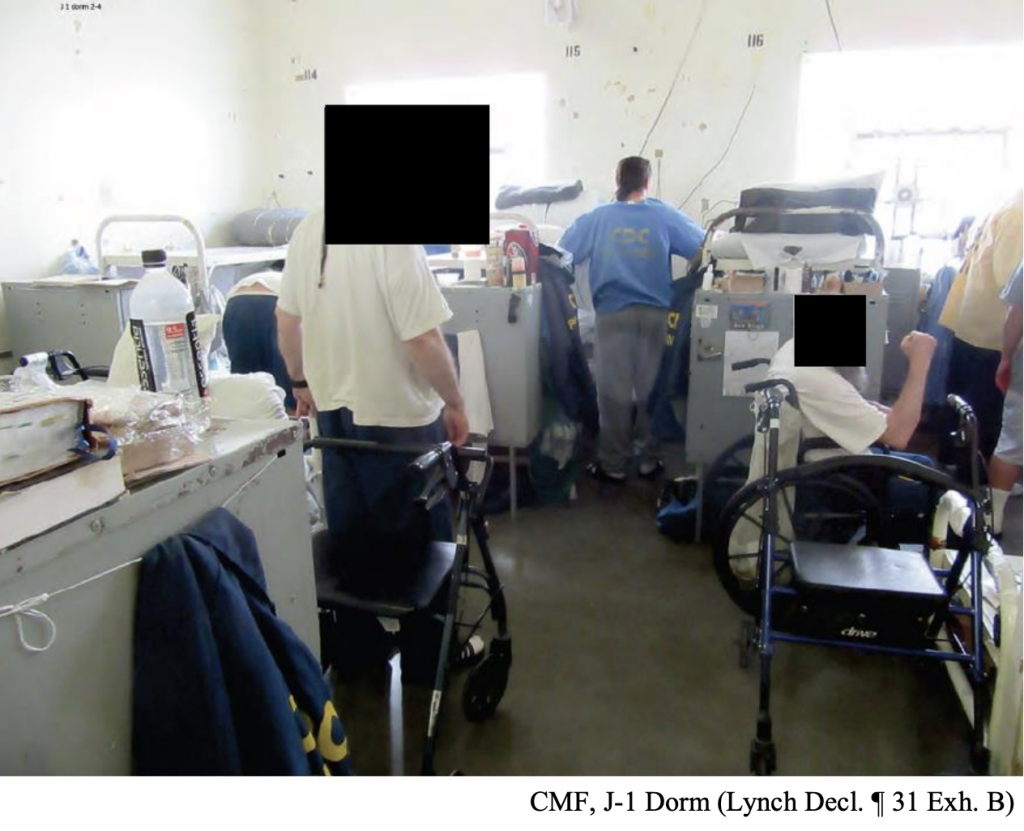

The generally unsanitary conditions and open dorm-style sleeping areas in the state’s overcrowded prisons cannot help but be breeding grounds for infectious illnesses like COVID-19, according to the motion.

“Dorm living requires people to sleep feet (and sometimes inches) from each other, and pass through narrow walkways to access bathroom facilities and common areas,” the motion states. “The only way social distancing would be feasible would be if the bunk beds were moved six feet apart, all double bunks were replaced by single bunks, and people never moved from their beds, including to dress, bathe, use the toilet, or eat.”

And 40 percent of the state’s prisoners live in dorm environments, most of which are stuffed with far more people than they were built to house. “Such conditions are a hotbed for infection, putting the lives of class members, staff, and thereby the outside community, at extreme risk.”

Image: Dorm inside California Medical Facility in Vacaville

Old and vulnerable

“The prisons also house tens of thousands of the people most vulnerable to death or severe complications from COVID-19: the elderly and people with serious underlying medical conditions,” said Sara Norman, Managing Attorney at the Prison Law Office.

“These conditions pose an unacceptable risk of harm not only for people who live and work in CDCR, but also as well as to the general public.”

In a declaration in support of the emergency order, Thomas Hoffman, former director of the Division of Adult Parole Operations within the CDCR stressed that recidivism rates for released “lifers” are extremely low, and that elderly people generally “age out” of illegal behavior.

“Of the 688 lifers released in 2014-2015, sixteen individuals (2.3 percent) were convicted of a new crime, the majority of which were misdemeanors,” Hoffman wrote.

“Based on my experience as a former peace officer, and former parole administrator, as well as my continued work in this field, it is my professional opinion that CDCR can accelerate the reduction of the prison population to address the COVID-19 pandemic without an adverse impact on public safety.”

Hoffman also emphasized that if CDCR does not act to prevent the uncontrolled spread of COVID-19 inside the prisons, “the consequences will be harmful to public safety.”

Image: Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison, Corcoran, June 2019

The calls from lawyers representing the state’s inmates are only one of many urgent pleas for Newsom and state officials to do something about the vulnerable prison system and the threat it poses to the rest of the state.

Ten days ago, on March 18, the ACLU also called on Governor Newsom to take steps to reduce the prison population. The ACLU suggested, among other strategies, granting early release to people with release dates in 2020 or 2021, and to prisoners who are at high risk of COVID-19 complications, including elderly adults.

The task force

There are some indications that the state is at least working toward prisoner releases.

On Friday, March 20, U.S. District Judge Kimberly Mueller ordered the creation of a task force of California officials, lawyers for inmates’ rights, and other stakeholders to come up with a plan to respond to the spread of coronavirus in the state prison system. This plan may include reducing the prison population.

Justice advocate Adnan Khan, the co-founder of Re:store Justice, whose murder sentence was vacated last year after more than 15 years in prison, reports that, in one prison where he has contacts, officials were evaluating prisoners in at least one of the facility’s dorm for possible release.

The approximately 200 people inside the dorm were asked questions about their age, remaining time on their sentences, and medical conditions, said Adnan, who also tweeted that he was on the phone with a friend inside when the announcement came over the loudspeaker:

BREAKING: (coming from inside prison)

While I was on a collect call with my friend who lives in a prison dorm of about 200 ppl, an announcement was made over the loudspeaker for people over 50yrs old and less than 15 months to release, to report to the podium.

(more)

— Adnan Khan (@akhan1437) March 27, 2020

In a new guide focused on ways the feds and local and state governments can fight the spread of COVID-19 in the justice system, Prison Policy Initiative’s Pete Wagner and Emily Widra point out that, across the nation, approximately 600,000 people are released from prison every year.

“If they are going to be released within the next few months anyway, why not release them now?” Wagner and Widra wrote Below are several of the ways PPI suggests states can reduce their prison populations amid the coronavirus crisis:

- “Parole boards can parole more people who are parole-eligible, and they can accelerate the normal review process, reduce the time between parole reviews, and eliminate the often months-long delays between parole decisions and actual release.

- Governors can grant partial clemency to people who are a short period away from parole eligibility so that the parole board can consider them for release now.

- Governors, legislatures and other agencies can change good-time formulas to allow people additional credit for time served…

- Governors can explore letting some people go on temporary furloughs who already meet most other criteria for release…

- Judges can resentence individuals to make them eligible for release on parole or on completion of the revised sentence.”

The state must act immediately to reduce overcrowding and, specifically thin the number of medically fragile prisoners in lockup, said Wagner and Widra.

The motion by the inmates’ attorneys to the panel of judges is equally emphatic.

“Without a swift and targeted reduction in the population, ‘[t]he conditions in CDCR’s prisons will undoubtedly result in the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus throughout the prisons,” the motion states. “Defendants are well aware of the crowding in their prisons and the substantial elderly and medically vulnerable populations in their custody. Their failure to act more quickly to reduce the prison population in light of this unprecedented crisis is troubling and constitutes further evidence of the need for urgent action by this Court.”

Image: California Institution for Men, in Chino.

They need to act quick or everyone incarcerated will be serving a death sentence. They cannot social distance or have personal disinfectant or have acess to proper needed cleaners to protect themselves from getting covid. Also infected C. O.s will spread it throughout the prison systems and then whom can care for hundreds needing medical care at once in our prisons . Slow the curve doesnt exist for prisons. Soon prisons will be Covid deathcamps. Gavin Newsom must act quick.