There are approximately twice as many boys than girls in the juvenile justice system in America. As a consequence, we hear more about young men in public policy discussions and in the press, when the topic turns to youth justice reform.

But according to an important new study just released by the Women’s Law Center, what we are missing when we look at the gross numbers, is the fact that when it comes lawbreaking that poses little or no threat to public safety, and offenses that are a direct result of violence or abuse and trauma in the home, girls are disproportionately more likely to be detained and arrested than their brothers.

For example:

In 2012, girls represented 29 percent of youth arrested nationwide, but they represented 76 percent of arrests for “prostitution,” (AKA “crimes” in which they are the victim), 42 percent of arrests for larceny, 40 percent of arrests for liquor law violations, 35 percent of arrests for disorderly conduct, and 29 percent of arrests for curfew violations.

In 2011, girls were 28 percent of delinquency cases, but they made up 41 percent of status offense cases. (Status offenses are actions that would not be considered crimes if committed by an adult, things like truancy or running away.)

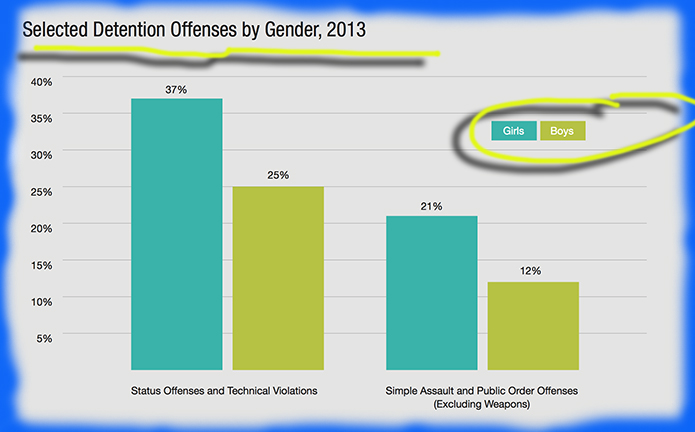

In 2013, 37 percent of detained girls were locked up for status offenses or technical violations of their probation, compared with 25 percent of boys.

Furthermore, for certain status offenses, rates for girls are even higher. For example, 53 percent of runaway cases in 2011 involved girls.

In addition, girls are unusually likely to be arrested for fights in their homes stemming from family dysfunction. For example, girls may become involved in a domestic fight when defending themselves against victimization or as part of a pattern of violence and turmoil among family members. Yet, when the incident leads to contact with law enforcement, write the study’s authors, girls “are treated as aggressors rather than victims.”

In 2013, 21 percent of girls were detained for simple assault and public order offenses (excluding weapons), compared with 12 percent of boys.

Sadly and predictably, girls of color are more likely to be detained than their white sisters. In 2013, Black girls were 20 percent more likely to be detained than white girls. And American Indian/Alaska Native girls were 50 percent more likely to be detained, according to the study.

IN CALIFORNIA LBQ/GNCT GIRLS HAVE IT THE WORST OF ALL

When it comes to girls who don’t identify as straight or what is known as “gender conforming,” the situation gets far worse:

A study of youth in California’s juvenile justice system found that 38 percent of the state’s LBQ/GNCT girls (lesbian, bisexual, questioning/gender-non-conforming, transgender) had been removed from their homes because someone was hurting them, compared with 25 percent of their straight and gender-conforming peers. The same study found that 49 percent of LBQ/GNCT girls in the juvenile justice systems had been homeless, compared with 30 percent of their straight and gender-conforming sisters.

California’s LBQ/GNCT girls who are justice-involved face additional challenges in their educational lives: 90 percent of LBQ/GNCT girls in the California juvenile justice system have been suspended or expelled prior to juvenile incarceration. In their homes, they experience high rates of family discord that may lead to adolescent domestic violence.

According to a 2015 survey of seven sites across the country, 40 percent of girls in the juvenile justice system identify as LBQ/GNCT. And a recent California study found higher rates of detention and incarceration of LBQ/GNCT girls for certain offenses: 41 percent of LBQ/GNCT girls were detained or incarcerated for status offenses and 8 percent were detained or incarcerated for sexual exploitation, compared with 35 percent and 3.5 percent of their straight or gender-conforming peers. Then once in the system, LBQ/GNCT girls report higher levels of self-harming behavior and are more likely to become targets of violence and sexual victimization, and be placed in isolation.

GIRLS IN THE SYSTEM AND TRAUMA

We know from multiple studies that kids involved in the justice system, are far more likely to have a higher degree of childhood trauma than are non-system involved kids.

Yet, as studies have been done that measure system-involved kids’ trauma in more detail, we see that girls trauma scores are consistently higher.

For example, in 2014, a Florida ACE study evaluated 64,300 youth involved in the Florida juvenile justice system, 14,000 of whom were girls. (ACEs—if you’ve some how missed this particular piece of useful jargon—stands for Adverse Childhood Experiences)

The study shows that the prevalence of ACE indicators was higher for girls than boys in all 10 categories. Sexual abuse, for example, was reported 4.4 times more frequently for girls than for boys. Forty-five percent of the girls scored 5 or more out of a possible score of ten when it came to adverse childhood experiences, versus 28 percent of the boys who scored 5 or more.

Another ACE study, conducted by National Crittenton Foundation in 2012, similarly found higher concentrations of adverse childhood experiences among girls in trouble with the law, with 62 percent scoring 4 or more on the ACEs scale, 44 percent scoring 5 or more, and 4 percent scoring 10, the highest score possible.

Among young mothers in the juvenile justice system, the scores shot still higher with 74 percent scoring 4 or more, 69 percent scoring 5 or more, and 7 percent scoring 10.

SO WHAT SHOULD WE DO?

The study’s authors offer a list of suggestions about what kind of policy changes would help, but their nine primary recommendations are the following:

*Stop Criminalizing Behavior Caused by Damaging Environments that Are Out of Girls’ Control

*Engage Girls’ Families throughout the Juvenile Justice Process

*Use Pre-Petition Diversion to Provide “Off-Ramps” from the Formal Justice System for Girls Living in Traumatic Social Contexts

*Don’t Securely Detain Girls for Offenses and Technical Violations that Pose No Public Safety Threat and Are Environmentally-Driven

*Attorneys, Judges, and Probation Should Use Trauma- Informed Approaches to Improve Court Culture for Girls

*Adopt a Strengths-Based, Objective Approach to Girls Probation Services

*Use Health Dollars to Fund Evidence-Based Practices and Programs for Girls and Address Health Needs Related to Their Trauma

*Limit Secure Confinement of Girls, Which Is Costly, Leads to Poor Outcomes, and Re- Traumatizes Vulnerable Girls

*Support Emerging Adulthood for Young Women with Justice System Histories

The study has lots more in the way of solutions and examples of municipalities that have made promising changes. But the first step, say the authors, is understanding that, “in the midst of the current ‘developmental era’ of reform, juvenile justice systems are routinely failing to modify promising system reforms for girls or even to collect data on how girls are affected by the problems systems seek to remedy.”

Bottom line: Our girls need our help.

AND IN RELATED JUVENILE JUSTICE NEWS…WHEN CALIFORNIA’S CROSSOVER KIDS BECOME NOBODY’S KIDS

“Crossover kids” are the California youth who start out in the foster care system, but then land in the juvenile justice system, for one reason or another. Or conversely, they begin in the juvie justice system, then cannot safely return to their families, so they become involved in the foster care system. Yet, as we’ve reported in the past (here and here), because of their dual designation too often neither system adequately takes responsibility for their well-being and crossover kids become nobody’s kids.

The LA Times’ Abby Sewell has a must-read story about one such boy named Jesse Opela, whose life has been overseen by LA County’s foster care system from the age of 2, and LA County’s juvenile probation system since the age of 12. Sewell and the Times received a hard-to-acquire court permission to able to follow the now-17-year-old’s “rocky trajectory” through both systems.

This excellent longread story is the result.

Don’t miss it.