“Art saved my life.”

These days my friend Fabian Deborah says those words in front of a wide variety of audiences. Sometimes the audiences are well-heeled adults at a fine art event. Other times Fabian might talk to a class of local elementary school children who, at first, stare at him nervously, like deer getting ready to bolt. But gradually his ability to be absolutely present with them starts to settle the kids down. By the end of class, a surprising number of students have painted pictures representing traumatic events in their lives that their teachers knew nothing about.

Born in El Paso, Texas, in 1975, Fabian’s family migrated west when he was five-years-old to what was then Pico Gardens and Aliso Village, the largest public housing project west of the Mississippi. His mother found low-paying piece work in a downtown factory sewing dolls. His heroin addicted father earned money transporting drugs from Mexico, a profession that cycled him in and out of prison.

During the height of the Los Angeles gang crisis, Pico-Aliso, as the mile-square area of the projects was called, was the home to six warring gangs, making it the most violent neighborhood in the city, according to LAPD stats of the time. Gang shootings took place almost nightly.

Fabian, who was a thin, sensitive kid, also coped with violence inside his household on the occasions that his dad happened to be home. When the hitting began, the boy would hide himself away with the small notebook he was never without, and he would draw. The worlds he created on paper became his one dependable form of protection from the emotional hurricaines that so often bore down on him.

At age 13, he found additional refuge in the streets by joining one of the Eastside’s most infamous street gangs. His street name was Spade. “You join a gang when you lose hope,” he explains. “I lost hope early.”

I got to know Fabian in the early 1990’s when I was researching a book about gangs in the projects, and the work of Father Greg Boyle. By that time, Fabian was trying to pull away from gang life and was starting to transition from spray-painting graffiti to working on color-drenched murals.

He had also begun smoking crystal meth to dull the pain that even a casual observer could see he carried. And, like his father before him, Fabian cycled in and out of juvenile, then adult lock-ups.

Hoping to steer Fabian’s obvious talent in a positive direction, Father Greg introduced him to Wayne Healy, a prominent Los Angeles-based Chicano-Irish muralist and painter. Healy liked the young man and took him under his wing as an apprentice. Through the relationship, Fabian began to discover himself as an artist. Even so, he couldn’t seem to shake whatever psychic injuries his early years had embedded. And he couldn’t shake the drugs.

In 1995, Fabian’s self-loathing became so overwhelming that, on one awful afternoon, he decided to kill himself. On impulse, he choose a particularly messy strategy. He sprinted into the oncoming lanes of traffic on the I 5 freeway assuming he’d be run down by some commuter going 70, and that would be that. Through blind luck, however, he made it across three lanes unscathed. But then, in lane four, he saw a turquoise Chevy Suburban coming at him. As he stared at the shiny grill of the truck bearing down on him, Fabian had a sort of religious experience in which some greater force somehow got him to the center divider, allowing the Suburban to whoosh by without doing harm.

The near-fatal freeway dash became a turning point. Fabian recommitted himself to painting. Then, a year later, he got clean and sober for good. A year still after that, in early July of 2007, I saw him for the first time in a decade. He showed up at a poetry reading that was part of a writing project I was involved with, in which some of his former homeboys were participating. “I’ve been completely clean for a year,” he told me after I spotted him at the back of the room and rushed to greet him. “I’m painting. I’m doing good.”

Indeed he was. And his work was remarkable.

Fast forward to today. Now that he’s saved himself through art, Fabian shows others how to find their own refuge and healing through the transformative power of creative expression. He gives talks about what painting can accomplish to at-risk teenagers in Chile, to transfixed students at Otis College of Art and Design, to the struggling former homeboys and homegirls who show up at his new downtown LA art studio.

He also has a day job as the Director of Substance Abuse Services and programing for Homeboy Industries, where he helps former gangsters in trouble with drugs save themselves through more prosaic means.

With the rest of his waking hours, Fabian spends time with his kids, and works on his extraordinary paintings, which have grown increasingly recognized for the way in which they illuminate the world that shaped him, a world that gave him both his wounds and his art.

“Drugs were my addiction,” Fabian told a class recently. “I would suffer without them. Now art is my addiction and I suffer when I don’t paint. So what do I do when I’m struggling? I paint. It’s something that no one can take away.”

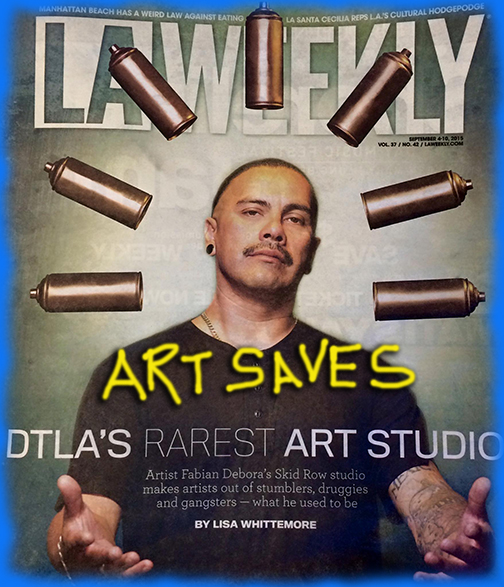

This past week, a wonderfully-written long-read cover article for LA Weekly, by Lisa Whittemore, celebrates Fabian Debora’s teaching, his artwork and his story. Here are some clips:

Two stories above the intersection, behind a reinforced steel door and two deadbolts, Fabian Debora’s Skid Row art studio, La Classe Art Academy, reflects the chaos and cacophony of the streetscape below.

Debora clicks on overheard lights. What was outside is now in: the graffiti, the drifters and the gangsters, and a cross-section of those who call downtown Los Angeles home.

The sense of having been swallowed by the city is uncanny. Debora’s studio is a cornucopia of these streets, past and present. In one painting Einstein, grinning mischievously, is tagging “L.A.” on a wall; a skateboard deck featuring the Virgin of Guadalupe hangs above a desk littered with paint pens; a memorial shrine with religious candles and dead roses is tucked in a corner. Smoke from a fresh sage bundle is curling into the air.

Canvases are propped on easels and stacked against one another on the floor. On one, a brown-skinned girl leans in against her older brother on the streets of Tijuana, smiling impishly. On another, Debora, arms outstretched, in fiery oranges and reds, stands life-size against a chain-link fence, offering his view of the Los Angeles skyline to his son. This studio space is the inside of Debora’s mind.

[SNIP]

Every Tuesday from 9 to 11 a.m., Debora opens his studio to clients from Homeboy Industries, the nonprofit job-services organization that works with ex-cons and former gangsters, and to teenagers from Learning Works, a charter school associated with Homeboy. Debora says the art academy is in its fetal stage, “barely getting its breath,” but the students roll in.

“I carry many feathers,” Debora explains. “A gang member, a drug addict, a felon, but I have redeemed myself through the power of art. It has given me my self-worth.” He pauses, then adds, “I feel it is my responsibility to use my art as a vehicle in helping kids and even adults to heal and recognize value in themselves and their surroundings.”

They come because they want to. Attendance is not mandatory. Three folding tables, covered in tagged-up butcher paper, brushes and paints, fill the studio. An easel with the day’s exercise faces the seats. The level of the students’ capabilities varies, yet no one hesitates. They stroll in, get seated and begin working on their projects. The Isley Brothers harmonize in the background and heads bob.

Debora doesn’t dictate instructions; he simply makes himself available and waits to be asked for guidance. The students thrive in an atmosphere where they are not judged and have nothing to prove.

“Whoever shows up on any given day is who I work with; it happens organically,” he says. “I’m not looking to work with the professionals, I want the stumblers.” When Debora laughs, the right side of his mouth hitches up in a wistful, childlike grin.

Debora has come a long way from tagging his moniker, Spade, on the L.A. River’s bed. He has crossed oceans and borders, visiting Rome and various countries in Central and South America, telling his dark origin story and rendering his images of Los Angeles. His artwork has been featured in exhibits, both solo and group, across the country.

In 2013 Debora painted a mural on the ceiling of the American Airlines terminal at LAX to celebrate the opening of a Homeboy Café. Macy’s has hired him to live-paint murals for events and conferences. From 2007 to 2012, Debora worked as a teaching assistant to Ysamur Flores-Peña at the Otis College of Art and Design. Edward James Olmos awarded him a scholarship and featured Debora’s story in a 2007 documentary, Voces de Cambio. Since 2008, the walls of Homegirl Café on Bruno Street have rotated his works.

People in the art community focus on the relevance and meaning behind Debora’s art. Isabel Rojas-Williams, executive director of the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles, a nonprofit that preserves, documents and restores the murals of L.A., says, “I have seen his techniques grow and expand over time. Every day he is more accomplished than the day before. … Choosing art as his way to express himself, using his brush, the walls and the canvas, Fabian is writing our history.”

Williams came to the United States in 1973 from Chile. In 2012, she was approached by the U.S. Embassy in Chile about sending someone there to speak with at-risk youth, and she immediately thought of Debora. He traveled to Chile, spoke with government officials, facilitated art workshops and met with kids.

“Fabian made a tremendous impact on those kids in Chile, not only as an artist or a mentor but as a human being,” Williams says. “He showed with his art how it is possible to transform absolutely any experience.”

Debora saunters through his studio with his hands in the pockets of his creased Levis. Bending over a student, he whispers in Spanish about las oportunidades de arte. His inky black hair is meticulously braided and hangs between his broad shoulders. Before he answers a question, he always pauses and looks off to the side. His replies are soft, yet every word is weighted. His eyes are almost black, smooth and wet like glass. They miss nothing. The same skill set that served him on the street serves him in class. He’s watchful, aware and anticipatory.

Read on. It’s worth it. Fabian Debora is the real deal.

Great story of reform and redemption.